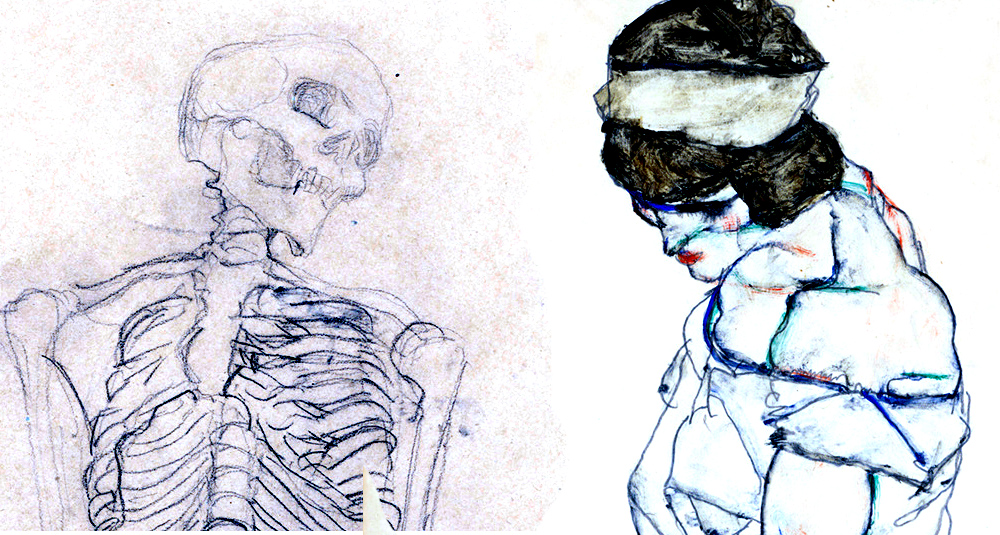

Left: detail from Two Studies for a Skeleton by Gustave Klimt; Right: detail from The Pacer by Egon Schiele

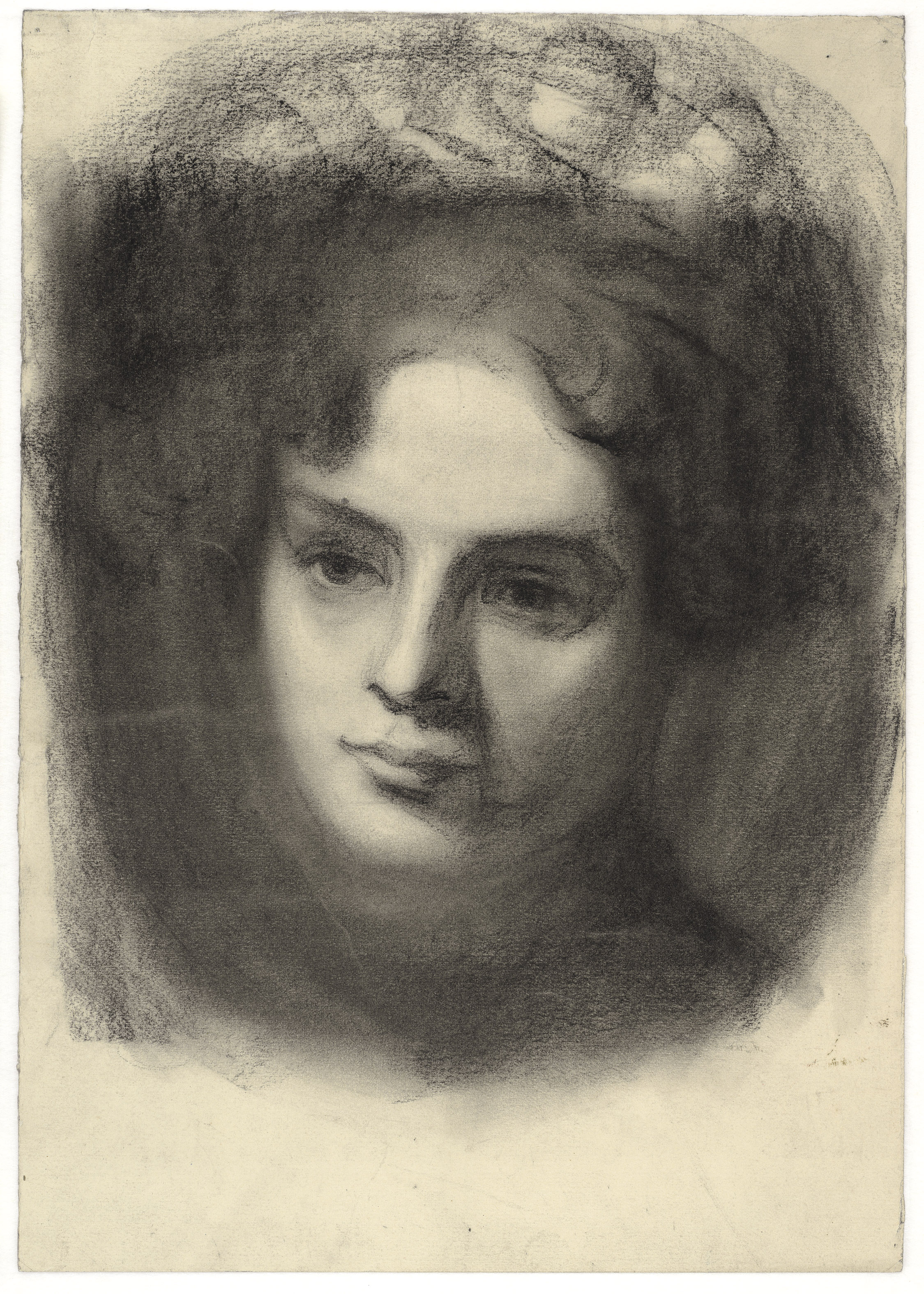

The year 2018 marks the centenary of the deaths of the Austrian artists Gustav Klimt (born in 1862) and Egon Schiele (born in 1890). Even after a hundred years, their drawings have a compelling immediacy, a sense of energy and presence, of searching and questioning, that still feels fresh. Both artists welcomed deep engagement with their art, a kind of looking that encompassed feeling and seeking.

Klimt was nearly thirty years Schiele’s senior, and the younger artist looked up to him, but their admiration and recognition of artistic skill were mutual. When Schiele asked Klimt if he was talented, Klimt replied, “Talented? Much too much.” Schiele proposed an exchange of drawings, offering several of his own sheets for one by Klimt, to which Klimt responded: “Why do you want to exchange with me? You draw better than I do.” Schiele was proud when his work was exhibited opposite Klimt’s in Berlin in 1916. Just a few years later, upon Klimt’s death, Schiele wrote: “An unbelievably accomplished artist—a man of rare depth—his work a sanctuary.”

For all their mutual respect, the two artists produced work that differs decidedly in appearance and effect. Klimt’s drawings are often delicate, while Schiele’s are regularly bold. Klimt’s drawings were typically preparatory for a painting, whereas Schiele considered his own as finished, independent pictures and routinely sold them. His drawings often employ intense watercolors of varying degrees of opaqueness that heighten the impact of the forms, while Klimt worked mostly in monochrome and line. And yet, despite these disparities, their works are related in ways that highlight what makes both artists’ drawings rewarding and challenging to contemplate.

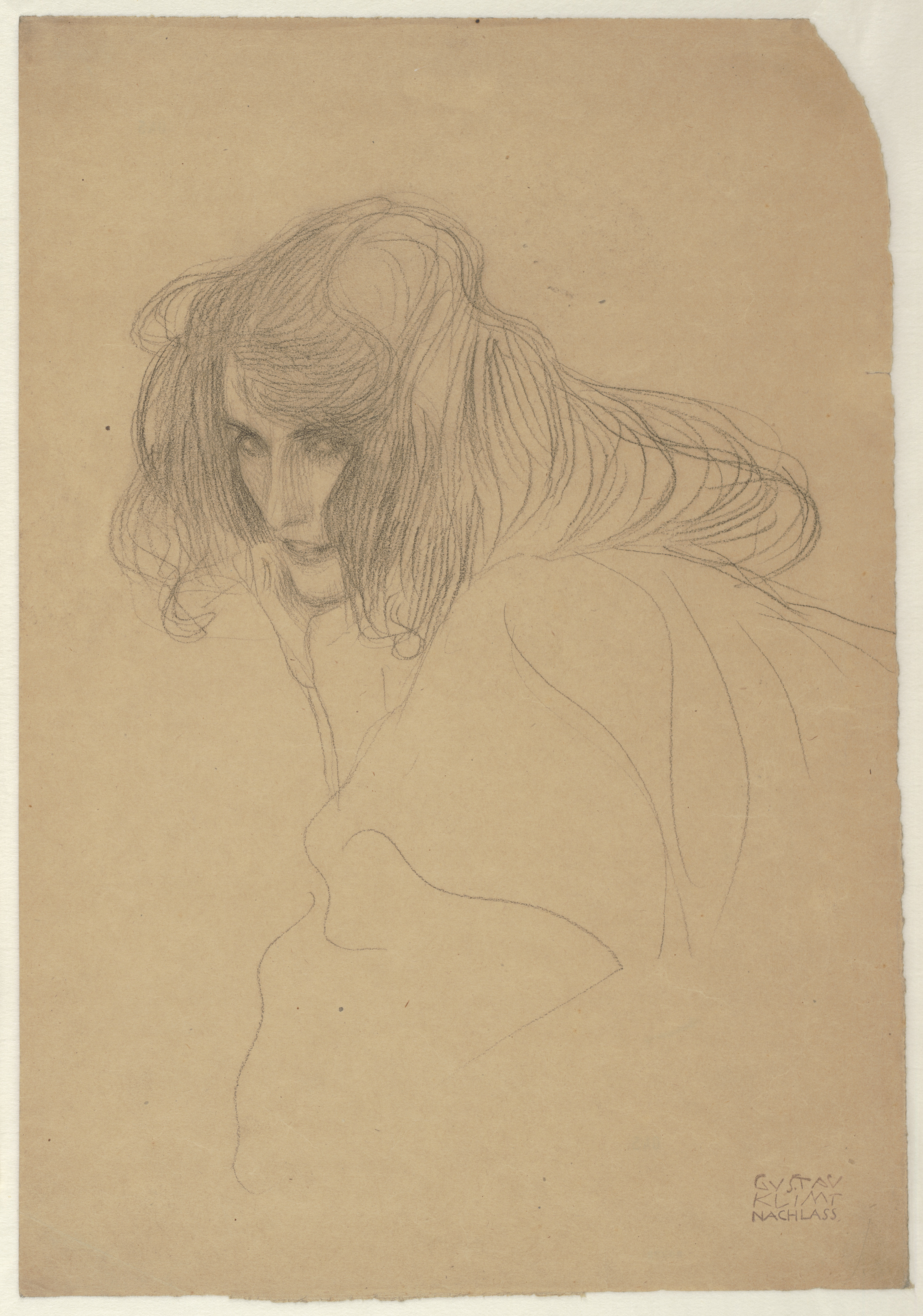

Portrait of a Woman in Three-Quarter Profile (Study for the Beethoven Frieze: Lasciviousness), 1901, Gustav Klimt

From Klimt and Schiele: Drawings by Katie Hanson. (c) 2018 by Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

from The Paris Review http://ift.tt/2ErqC6V

Comments

Post a Comment