No importa lo que pasa en la hoja de papel, lo importante es lo que pasa dentro nuestro.

It’s not important what happens on a sheet of paper, the important thing is what happens within us.

—Mirtha Dermisache

Despots, from those who composed the efficiently murderous junta that ruled Argentina to the petty kakistocracy that runs the United States today, curb the written word because they fear its expressive power. They haven’t learned that what they should fear is not written language but, instead, the very impulse to write. It is more prevailing than literature, capable of surviving where art cannot.

The writings and artistic practice of Mirtha Dermisache are a testament to this. Her work, which she created while living under the junta in Argentina, is lasting and subversive even though she barely penned a legible word. One could argue that writing is a state of being in conflict—with oneself, with one’s subject, with one’s government, or with one’s community. But the unconscious impulse to write comes before the word, and it does not always take the form of language. Everything that follows—in how we traditionally conceive of writing—is an attempt to capture that compulsion, to make approximate marks that convey our thoughts to others. This is what John Berger referred to when he wrote, “The boon of language is that potentially it is complete, it has the potentiality of holding with words the totality of human experience.” Prose, he came to believe, expressed something that was far from truth because it was too artificial and too trusting, it did not “speak to the immediate wound.”

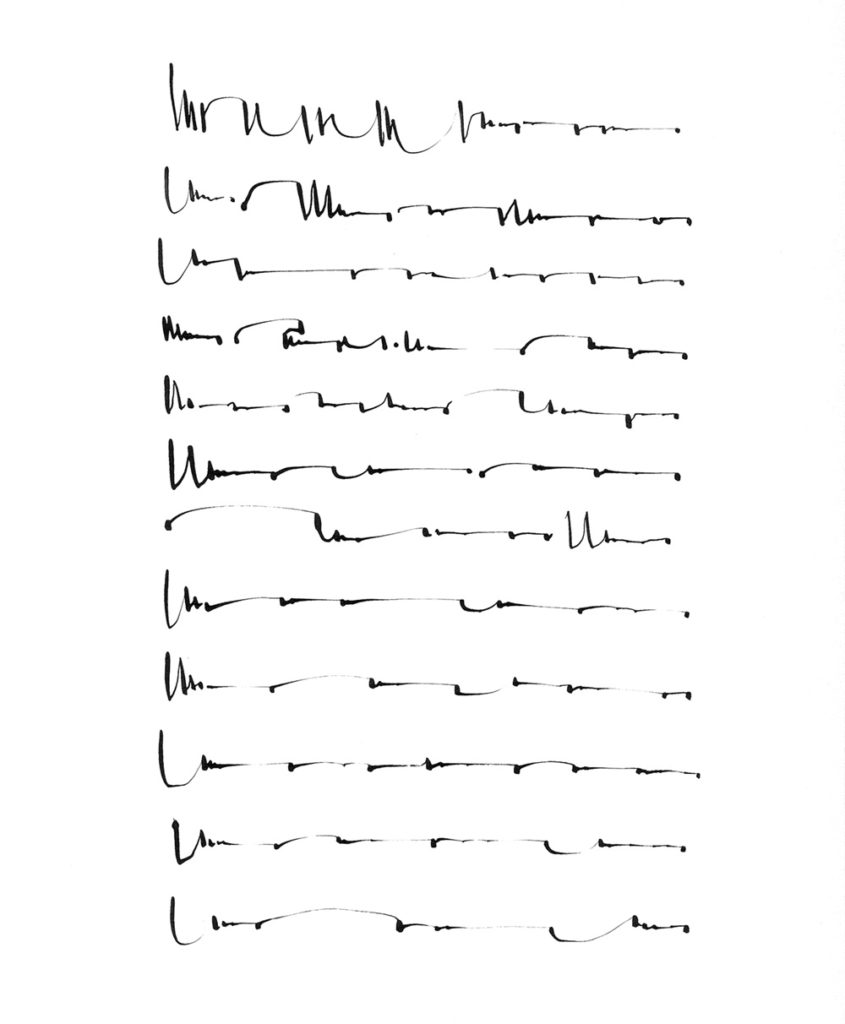

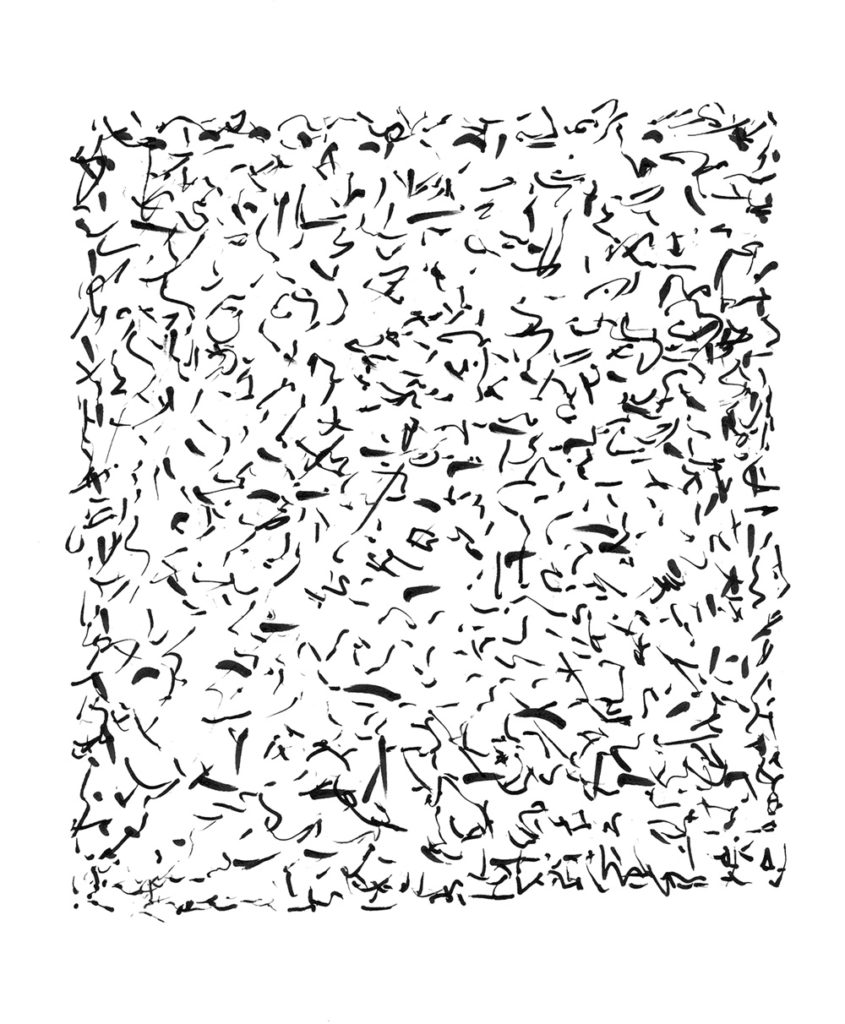

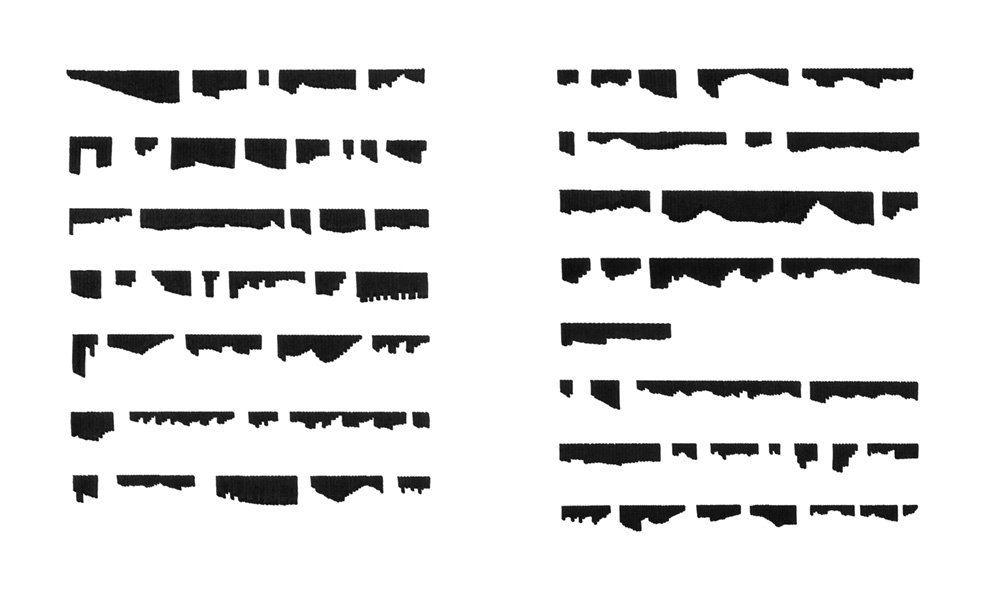

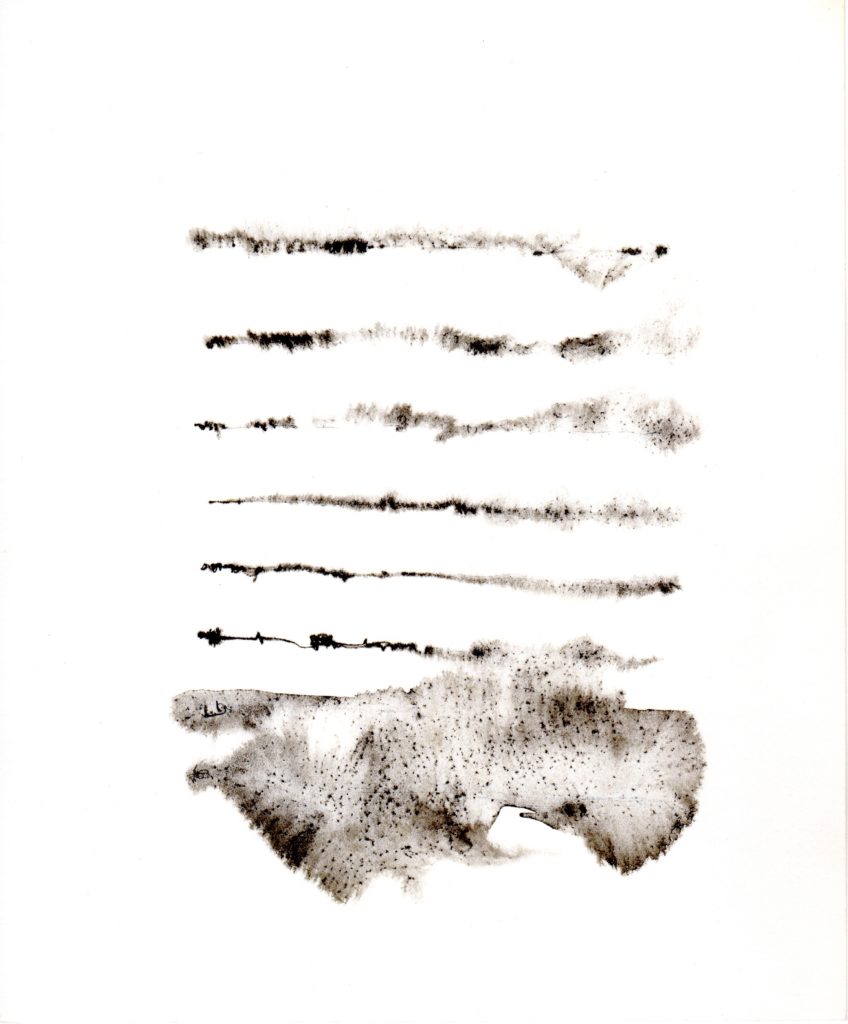

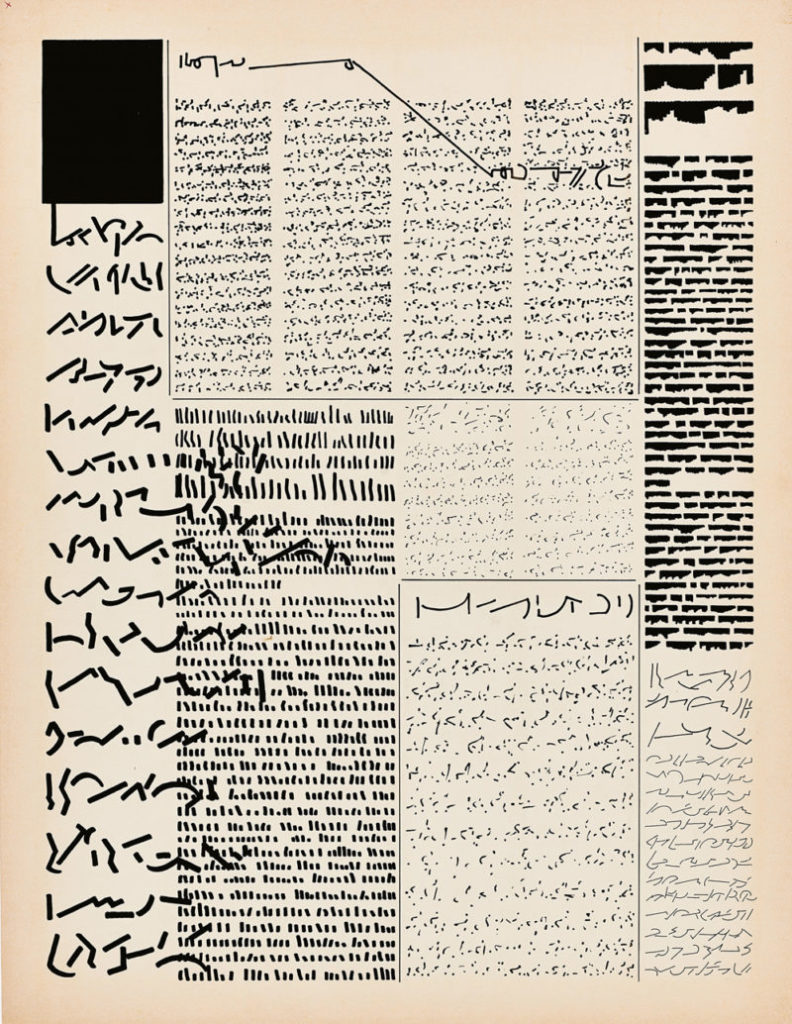

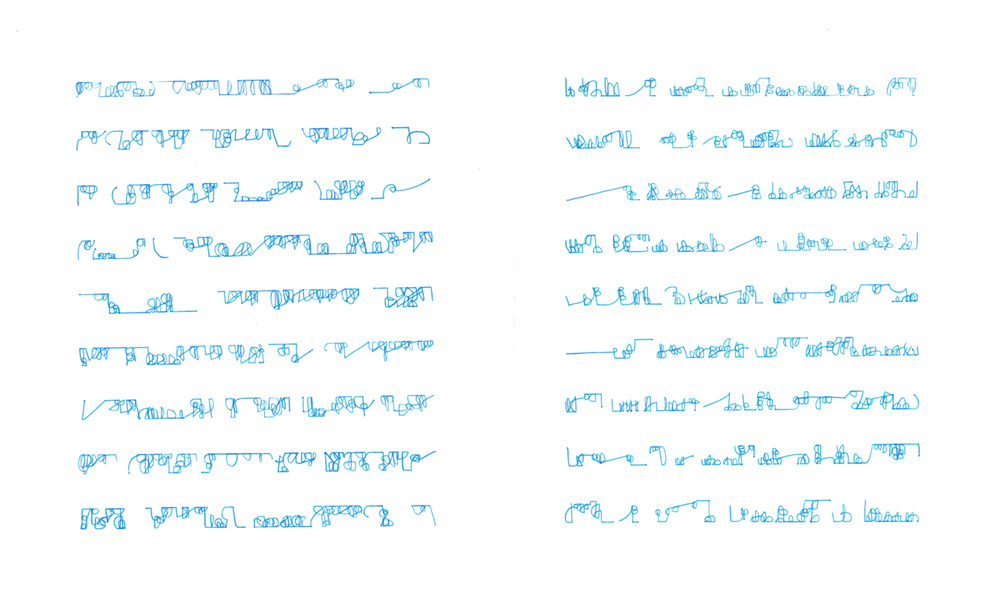

Dermisache’s letter-ish scripts twist and curl, bleed into amorphous shapes, and run cleanly across lines like telephone wires. She scribbles, fills in horizontal lines running one above the other, or blocks out polygons and abstract hieroglyphs into tidy rows. She writes in black, blue, seeping shades of red. Yet for all the shapes and forms, we recognize her marks immediately as language. They compose a sort of urlanguage, which may, on occasion, vaguely resemble the sleekly linear letters of Arabic or the regimented cursive of South-Asian abugidas, but follow no grammar or syntax. They fall into a tradition of asemic writing—writing without semantic content—which dates to the Tang dynasty, perhaps originating with two Chinese calligraphers affectionately referred to as “the crazy Zhang and the drunk Su,” who excelled at wild, illegible calligraphy. The movement was embraced in avant-garde movements, by Henri Michaux and Robert Walser in the 1920s and later, in the 1950s, by artists such as Cy Twombly and Isadore Isou. At a recent exhibition of Dermisache’s work, she was shown alongside her contemporaries Guy de Cointet and Gerd Leufert. In comparison, their works are more studied, as if they were composing semiotic tricks or compacting rather than expanding a thought. While avoiding language they are nonetheless functions of it, in as much as their work hinges on expressing some linear idea. But if Dermisache wrote words, they were empty of meaning. She sought to free her lines from their tether to representation.

Mirtha Dermisache, Sin título (Texto) , no date, c. 1970s. From Mirtha Dermisache: Selected Writings.

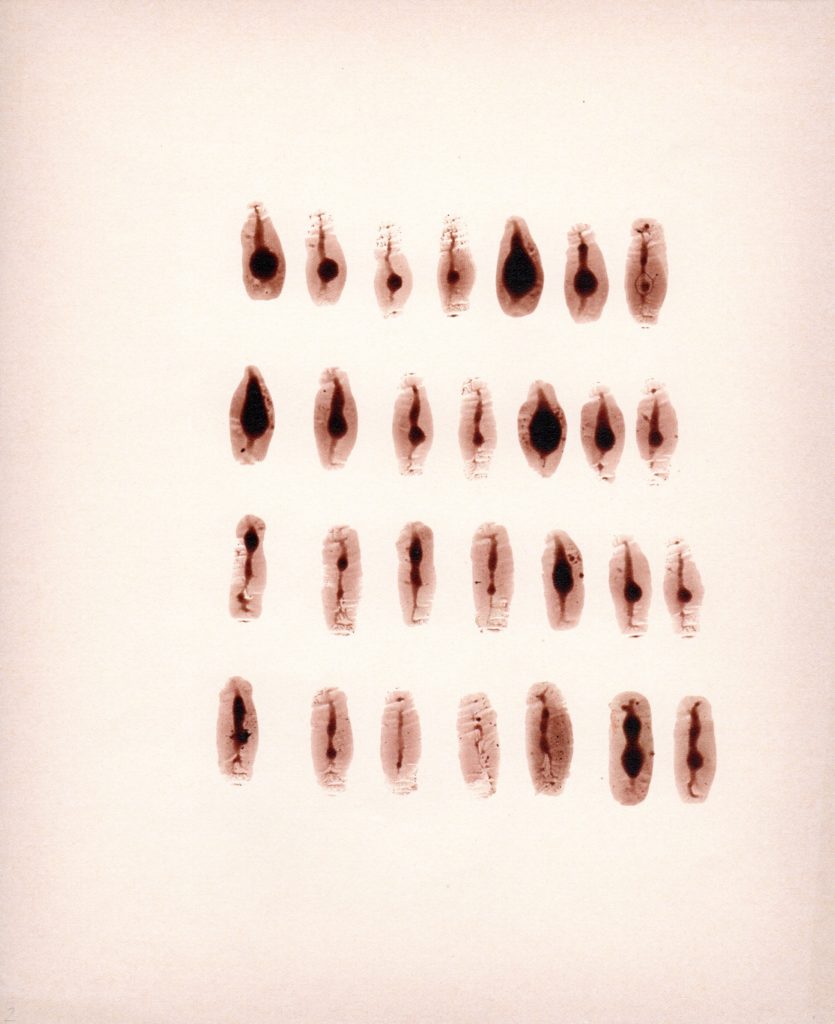

Nonetheless, Dermisache’s works do rely on some received wisdom—how could they not? She gave her writings simplistic titles, beginning in 1969 with Libro No. 1, an illegible 500-page tome, and numbered sequentially after that. In many of these books, she discards the identifiable characteristics of books themselves—empty colophons and covers left blank. The books shipped with inserts denoting the publisher’s information, but those were marked with notes requesting that they be discarded. Her Diarios are copies of the daily newspaper with information translated into nonsensical script. In 1972, Dermisache contributed to the exhibition Art and Ideology at CAYC in the Open Air, organized outside el Centro de Arte y Comunicación in Buenos Aires. The Diarios were placed on public benches, like finished newspapers left behind. In an oft-quoted letter, Roland Barthes wrote to Dermisache that her work suggested “the essence of writing.” Dermisache turned language back into something resembling pure, unformed clay.

In 1971, Dermisache founded the pedagogical Workshop of Creative Actions as a means of inviting non-artists to create art. Out of that grew las Jornadas del Color y de la Forma, the Days of Color and Form, in which the public was invited to participate in collective art-making. At their heights, the workshops drew 15,000 participants, and 18,000 to las Jornadas. Rather than employing rhetoric to inspire resistance, she cultivated a community by attending to its desire for missing unity. This conception of participatory democracy was essential to Dermisache, who, for years, avoided exhibiting her work in galleries. As she said in an interview, she preferred to see her work printed

Because it was the only space adequate for the graphics to be read.… I was radically opposed to putting them on the walls like a painting. There are people who saw the books and told me to take out the pages and put them in frames on the wall. I said no, this is not an engraving, it is not a painting, it has to be inside a book, to be read.

Mirtha Dermisache, Sin título (Texto), no date, c. 1970s. From Mirtha Dermisache: Selected Writings.

In 2004, when Dermisache was in her sixties, the curator of the recently closed Henrique Faria exhibition, Florent Fajole, helped the Argentine writer assemble an editorial framework that would position her work when exhibited in galleries. On the day I visited, Henrique Faria turned out to be closed, but another writer and I were allowed to wander while the gallerist took inventory. Prints by de Cointet and Leufert were framed, but Dermisache’s asemic writings were simply pinned to walls or laid across tables in the top floor of the brownstone. Guests were invited to sit, read, and rearrange them according to their own internal sense of their meaning. Three offset lithographic prints were stacked for the taking, which I now keep in a folder under my desk, taking them out from time to time. I’ll flip them over or lay them out in various arrangements just to see what happens. Located somewhere between what we know as art and language, Dermisache’s asemic writings are theurgic: they are ritualistic marks meant to heal one’s relationship to a universal presence. They take little interest in expressing the singular vision of the author and artist. They undermine the notion that the end state of an author is to be published, an artist to be framed. Through their structure, I recognize her writings as language but, unable to read them, I find myself at a loss for words.

“‘Mine’ doesn’t mean anything,” Edgardo Cozarinsky wrote in an early published note on the artist. “It only has value when the individual who takes it up expresses himself through it.”

Dermisache died in 2012 and, during her lifetime, she preferred anonymity. She rarely spoke about her political affiliations. In an interview in 2011, when she was asked how her work engaged with politics, she replied, “The only time I referred to the political situation in my country was in the Journal. The left column on the last page is an allusion to the Trelew dead. This was in 1972. Apart from this massacre that did impact me, as it impacted many, I never wanted to give a political meaning to my work. What I did and continue to do, is to develop graphic ideas with respect to writing, which in the end, I think, have little to do with political events but with structures and forms of language.” And yet, in another interview that same year, she acknowledged the potential for a political dimension to her work. It lay in the disjunction between its linguistic malleability and the rigid structure through which it was received. She said, “For me the liberation of the sign takes place within culture and history, and not on their margins. In this sense my work is not behind the times, at all. Graphically speaking, every time I start writing I develop a formal idea that can be transformed into the idea of time.” In our current environment, it is difficult to look at her work and not think about the impossibility of discourse, the primacy of self-expression, and the fallacy of a shared objective language, not to think of this art as both radically political and necessary today.

An old poet I know and admire is fond of saying that in the coming ruins—and they will come for us, he insists—when we find ourselves again huddled in caves by firelight, we won’t be reading each other’s novels; we’ll be reciting each other’s poetry. I’ve always thought he’s half right. We won’t be reading novels, no, not for some time, but poetry won’t be the first thing we restore. In the ruins, the words we once knew will fail us too, and we’ll be left scrawling again along the walls in some noble attempt at inventing a new language to capture all that we’ve seen.

Mirtha Dermisache: The Otherness of the Writings, curated by Florent Fajole was on display at Henrique Faria Fine Arts, NYC, December 1, 2017–January 20, 2018

Mirtha Dermisache: Selected Writings, co-published by Ugly Duckling Presse & Siglio Press, will be published March 26, 2018.

Will Fenstermaker is an editor at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and an associate art editor at the Brooklyn Rail.

from The Paris Review http://ift.tt/2nrwFjG

Comments

Post a Comment