Tom Sachs: Tea Ceremony at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas (which closed yesterday) was a vast and complex exhibition of ideas within ideas about ideas, wherein the protocols of the Japanese tea ceremony and those of NASA’s space program are revealed to express opposed yet deeply similar understandings and even longings. There is a “me upon my pony on my boat” sort of yearning throughout this profound yet willfully childlike theater of imitation. Lucia Simek, an artist and the communications manager for the museum, and a friend of both Sachs and the writer David Searcy, arranged for the two to get together in the spirit of their weirdly similar interests—rockets, Mars, Japanese tea bowls, and switchblade knives.

Part 1

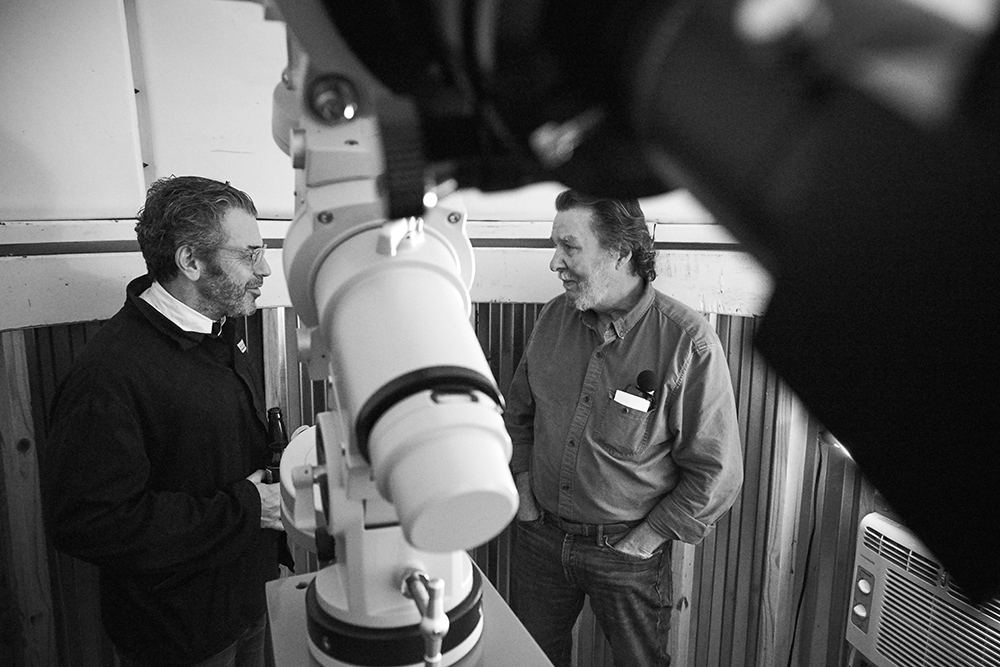

David Searcy (left) and Tom Sachs (right) standing by Sachs’s Big Cock, a reconstruction, in red-painted 1/4 inch plywood puzzle pieces, of Brancusi’s famous abstract rooster.

SEARCY

I had great doubts after just seeing shots of this piece in the press. It looked like easy ironies. I didn’t realize this was after the Brancusi, I thought this was Jean Arp or something. But immediately, when I saw it in person, I came upon this thing that’s just adoration. I thought to myself, This is a guy who does crossword puzzles with a ballpoint pen.

SACHS

(Laughs.) Thank you. I really appreciate that. My drawing teacher was Guy Goodwin. He taught at Cooper Union, and at Bennington, where I went. He’s a legend at helping each person find their way into drawing. And for me, he was just, Draw it! And sometimes he’d like smack me, not in the face but like in the back (Tom smacks himself in the back of the head) just to kind of shock me, and to say, Just go!

SEARCY

Well, he sounds like a Zen master with the whack on the head, you know.

SACHS

Yeah, yeah—and so I went to Brancusi’s atelier in Paris, measured it, built a form that was a quarter of an inch less than this and then just went. I’m not skilled, but I just threw a lot of tenacity and care into it.

SEARCY

How many pieces wound up on the floor?

SACHS

A big pile—but those scraps are sacred. I’m very careful to make sure people don’t sweep up the scraps. Because, you know, you’ve got the negative of it on the floor. So that’s a good place to start with the next idea.

SEARCY

Wandering around, looking at everything in this show—there are pieces deriving from NASA’s space program, tea ceremony, iconic modern art—you almost always go for the artifact, the preexisting idea. You reproduce the idea. And it’s about the idea. It’s an idea about ideas. And I don’t see the natural world appearing here at all except when you look at the ground. That’s the world. That’s the dirt. That’s the rock. Is that your default?

SACHS

The ground?

SEARCY

The ground like in there (indicating the next room, the Outer Tea Garden, where a faceted, gray, stonelike “berm” surrounds a koi pond).

SACHS

Oh, the berms. Yeah.

SEARCY

That’s a natural object. It’s not an idea of the world. It’s the world.

SACHS

Right. I think I’ve started with the things I love—like McMop Buckets (referring to his foam core reconstruction of a McDonald’s mop bucket with ringer) and modernist sculpture and spaceships. But then to go do nature is tough because nature is so refined—it’s so sophisticated and complicated and simple. But you know, if you look at that Noguchi over there (a large stone sculpture by Isamu Noguchi on loan from the Noguchi Museum to join Sachs’s Tea Garden)—that’s a found rock, he did just a very few interventions.

SEARCY

The scholar’s rock tradition, almost.

SACHS

I think probably ninety percent of it was just selecting the right rock and putting it at the right angle, and everything else was about ten percent. So, yeah, I think the way I’m doing those berms is trying to keep it to the minimum number of gestures to still look like nature and yet not be too shitty.

SEARCY

What it reminds me of is a certain kind of camera they use in astronomy—they’re all terrifically sensitive, and if you’re looking at a planetary object or a nebula, then that’s what you get, but if it goes to black sky it starts picking up its own static. You tune the gain way up to a place on an empty field and this is what comes out.

SACHS

So you just see—what do they call it?—the artifact.

SEARCY

Yeah. It’s like you’re just looking at the world itself without idea imposed upon it. You get this wonderful—as my wife who is an art historian knows—Giotto-like late medieval ground. And there’s this sense, speaking of Japanese tradition, that the idea is not really understood until it’s imitated. There’s this sixteenth-century Korean rice bowl that’s a Japanese national treasure. The story goes, the student of tea asks the museum curator, How can the Koreans know how to make such a wonderful tea bowl? And the reply is, Well they can’t know. If they knew what they were doing, they couldn’t make a beautiful tea bowl.

SACHS

So it’s just by virtue of the Japanese regard.

SEARCY

Right, the regard creates the idea. And, I mean, your regard almost remakes the idea.

SACHS

I’m trying to understand what you’re saying. I’m very selective about the things that I choose to represent and make. But I never really thought about how that’s quintessentially Japanese—like stealing Korean rice bowls to make them into these kind of things.

SEARCY

It’s not a national treasure until you know it to be.

SACHS

Right. And that’s the job of the artist or the curator or the scholar or … I don’t know how that happens.

SEARCY

I don’t know either. I don’t know either. (Laughter.)

SACHS

But I know that in the things we choose to represent, there are some things that work out better than others. And Marcel Duchamp, he’s the guy who takes the urinal and puts it on the pedestal and says, Okay, now this is art. And that’s regard.

SEARCY

Sure. Yeah, exactly.

SACHS

And then I don’t know if you are aware of this word mitate? It’s a Japanese word that means using the wrong thing for the right reason—or appropriation. I think that guy Rikyu, Sen no Rikyu, the sixteenth-century father of the way of tea, was the first guy to do some of what Duchamp was doing, with that Korean rice bowl.

SEARCY

Well, it starts in the sixteenth century with tea, and then there’s the Renaissance. The moments of self-consciousness. Modern art is an exquisite perfection, or concentration, I should say, of self-consciousness. And that’s why it’s so easy to think, well, it’s about irony. But irony is nothing. Irony is not even a gate. Irony is a vast illusion. You think you’re getting leverage with irony—you’re not. You’re just posing. The self-consciousness that occurred with that wabi thing—the sense of beauty that celebrates the struggle, the simple and imperfect gesture in the making of a thing. What’s more impossible than to contrive to be absolutely honest and natural? It’s almost the beginning of modern art, in a sense, in that moment—that tremendous self-consciousness.

SACHS

Well, I think that’s a really important time. I think that’s one of the reasons why I’m so interested in the tea ceremony. And also, by the way, every samurai movie you’ve ever seen takes place in that same period. Like, we don’t really know anything else about Japan before or after.

SEARCY

I just saw A Space Program.

SACHS

Yeah.

SEARCY

And even if there had there been no tea ceremony in the middle of it, it would nonetheless have spoken very clearly to what happened in here (indicating the adjoining Tea Garden and Tea House)—I mean, to me, in the middle of this utsushi, there’s this caution. The red-and-white-striped barricades. That’s important—the idea is startling. Be careful! Ideas are startling!

SACHS

Oh that’s (laughs)—I never really put it together.

SEARCY

I just think it’s terrifically important. I was standing there watching my wife participating in the tea ceremony for about an hour and a half, and all this calm is surrounded by this signal—Be careful! Look out! Go away! Don’t come any … Oh God, an idea! This is terrifying stuff!

SACHS

I’d never thought about that.

SEARCY

Peacefulness is terrifying.

SACHS

It is.

SEARCY

And the outer space and the inner space.

SACHS

Don’t they do a thing—aren’t there some tests where they put you in an orange room and you go a little crazy, so they put you in blue and green rooms? I remember when I was a kid, we lived in an old house and my mom was redoing my bedroom and said to me, You’re old enough to pick the color. I was into the New York Mets, so I said, I want the walls orange and the furniture blue like the Mets. But I didn’t realize I was buying into an orange room, and I must have lived in that room for a decade—in this orange room, right? And I think maybe that’s one of the reasons why I’m so fucked up (laughs).

SEARCY

My excuse is I fell out of a tree. Yours is much more interesting.

SACHS

You fell out of a tree?

SEARCY

Yeah, out of a tree.

SACHS

Did you hit your head?

SEARCY

Yeah, yeah.

SACHS

Awesome. It so worked in our case.

SEARCY

Do you have time to come over?

SACHS

Yeah.

SEARCY

That would be great. I, too, have rockets (in silly Russian accent). I, too, have tea bowls.

SACHS

Amazing.

Part 2

Across town at David Searcy’s place, standing before a floor-to-ceiling glass case of Japanese tea ware, seventeenth century to modern, several repaired by the traditional Japanese gold-lacquer process called kintsuge, which Tom Sachs also employs with certain of his NASA tea bowls.

SEARCY

I love your kintsuge. Here is a very elaborate kintsuge on a very undistinguished bowl—it became the fashion in the nineteenth century to recover these old tea bowls as “wasters” from kiln sites and restore them as if they were precious. And the regard for them makes them precious.

SACHS

Yes.

SEARCY

Like we were talking about.

SACHS

I’m making the same tea bowl over and over again. The bowl that I’m making now is for Johnny Fogg. He comes over, and it’s too thick, too thin, too heavy, too light, too big, too small—we’re making this Goldilocks bowl. I’ve made six hundred of them, but we’re always trying to refine and I’m getting closer and closer—like the Fibonacci sequence, always getting half…

SEARCY

Or Zeno’s Paradox.

SACHS

Is that what it is? Is that what it’s called?

SEARCY

Yeah, you can only get half.

(Drifting out onto the back deck toward a little observatory, entering the observatory through a tiny door.)

SEARCY

It’s kind of like the tea room—you have to bend down.

SACHS

As you should.

SEARCY

It’s kind of crazy to have an observatory in a forest, my backyard overhung with trees, but somehow, again, the struggle is part of it. (A large refracting telescope is the object of attention.)

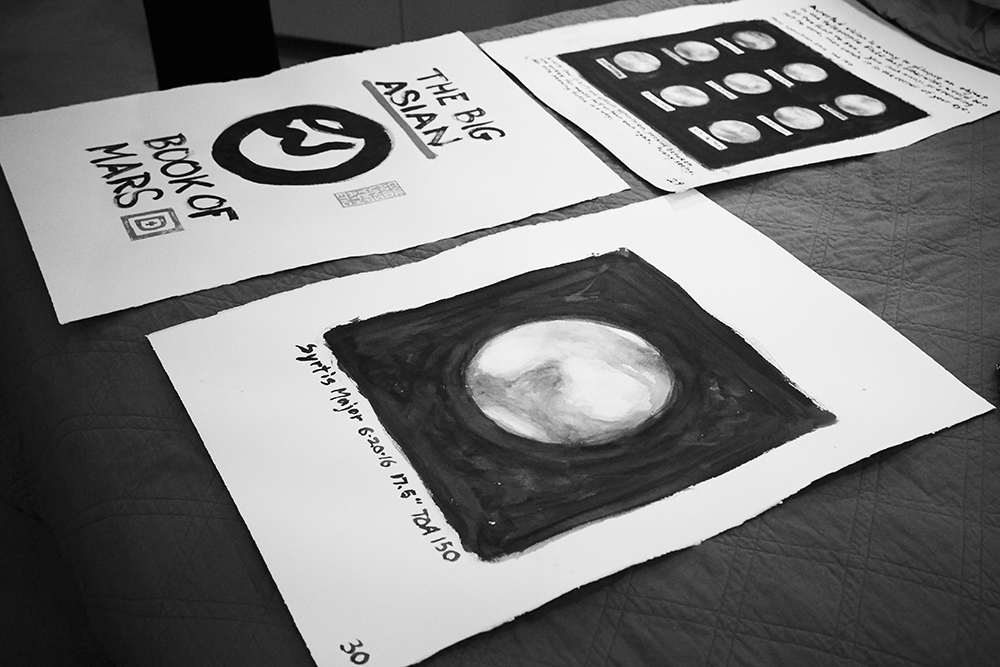

There’s this thing, this book I’ve been working on for a while called The Big Asian Book of Mars. I’ll just do a few pages, perhaps, a year—big pages … thirty by twenty-two inch ink drawings. I’ve got my little drawing table down here and I’m peering at Mars through the telescope. I’ve got an hour between the trees at biannual Martian opposition and you got to paint the damn thing within that period of time.

SACHS

Cool.

SEARCY

And I’m not an artist, so it’s always a struggle. But there’s something about the peeking out from between the trees that’s like peering at something through a hole in the fence … I love telescopes more than I love the heavens.

SACHS

Well, there are three reasons people are into things—spirituality, sensuality, and stuff. (Laughter.)

SEARCY

I’m in the final category.

SACHS

Me too.

SEARCY

I try to squeeze something philosophical out of it. I have this idea—it’s very dear to my heart—that vertical is only a special case of horizontal. That we think flat—and your Space Program, which all takes place on the flat surface of the earth is just gorgeous—you get lost in that.

SACHS

You know, as much as I love the art work, it doesn’t mean anything without the aspiration of the spiritual, and the sensual of course. Without those there’s no point.

SEARCY

I think that we think horizontally. We live horizontally, and I think when we look up we just tilt the horizontal up in some strange way. But that sense of “as above, so below”—I mean the whole idea of outer space is not that different from that of inner space. You’ve got the great emptiness up there and the great emptiness in here. And you’ve got those working together, explicitly nested, you know, in the Space Program and the Tea Ceremony. To have those two things going on together, it’s exhilarating and a little bit terrifying. (The group drifts back inside.)

SACHS

I heard that you have a switchblade collection.

SEARCY

Well, I have a few left. I have some nineteenth-century ones, which are hard to find, upstairs. (Pulls a grungy old early twentieth-century Schrade switchblade from a cabinet.) This is the one that got me going again. It’s not a very good example. It’s got a weak spring (sound of blade snapping open) … clunk.

SACHS

I’ve recently become inspired because there are so many good modern ones that are out there lately. The one that I think is the best one is by Spyderco, and they make, I think, the nicest heavy good one. Like, three hundred bucks—beautifully machined.

SEARCY

There are a lot of custom makers who are making some extraordinary ones.

SACHS

Those are great but they’re too fussy.

SEARCY

Yeah.

SACHS

I have a thing called Rock Steady from Japan that someone gave me and I’m pretty sure you carry it if you’re a yakuza, for when you have to cut off your finger. You take this thing out and …

SEARCY

“This is the one …” I can see the TV commercial.

SACHS

“When you have to … ” (Laughter.) Because it’s, like, heavy and it’s all I would use it for. I keep that in a drawer. (Sachs turns to look at a massive, shiny-knobbed, 1950s National HRO-60 receiver.) And is this a ham radio ?

SEARCY

Yeah—I love these guys.

SACHS

Are you communicating?

SEARCY

No, I don’t have a license for that and all they talk about is their equipment and their failing health.

SACHS

We got ’em for the team—pirate style, because of the Internet now. It’s thirty dollars, eight watts. Totally irresponsible.

SEARCY

I love these things because they don’t have all the filters. You can hear all the noise in between stations. You can hear the ether out there. You’re sensing the difficulty and the texture of the transmission. (Moving into the hall, there’s a display of five mizusashi—large, ceramic fresh-water containers for the tea ceremony.)

SACHS

Are those water containers?

SEARCY

Yeah, those are my favorite tea vessels. I love mizusashi—little buckets. That guy (indicating a rather brutal rectangular vessel) might be pretty old. It might be like late sixteenth or early seventeenth century. Iga ware—which is weird stuff.

SACHS

That’s really cool

SEARCY

It looks like something you’d keep your, uh …

SACHS

Ashes.

SEARCY

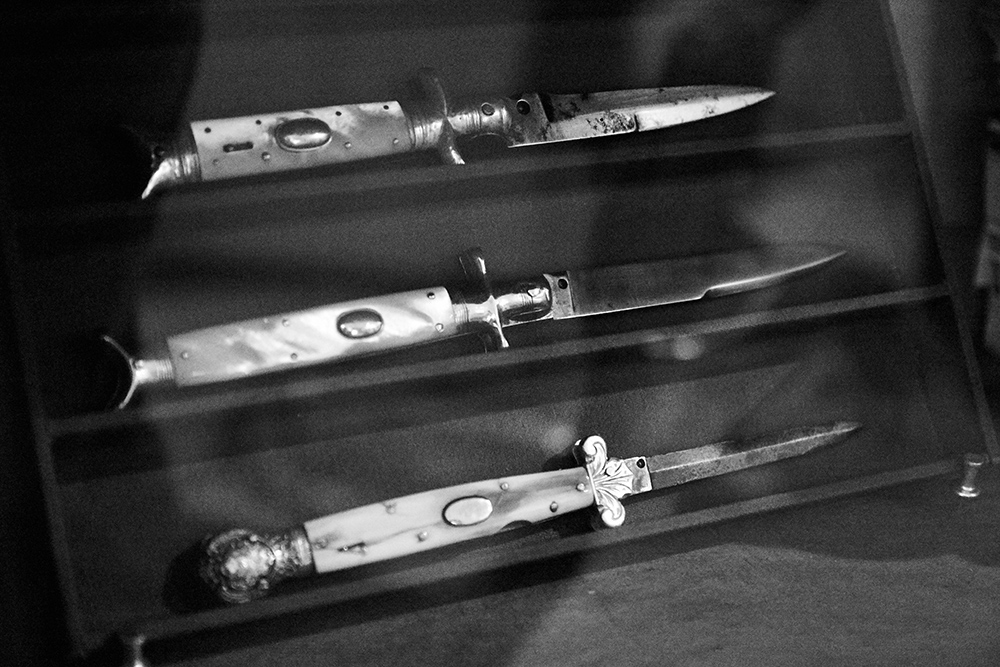

… waste plutonium in or something. (Laughter.) Anyway, if you’ve got time for one brief ascent—come up. (Sounds of climbing a creaky spiral stair, then moving to a small display of three very old switchblade knives.)

SACHS

Oh, beautiful.

SEARCY

The top one is Belgian, the one under it is French—those are probably around 1850. And the British one on the bottom is about the same period, I think. But the idea that that switchblade gesture, that threat, was available a hundred and fifty years ago …

SACHS

Must have been terrifying.

SEARCY

You know—just click. One thinks of that as 1950s stuff, that’s Rebel Without a Cause. How do you do that dressed like those guys were dressed? What would it have meant? You know—click. It would have been worse, I think.

SACHS

Well, you wouldn’t see it coming.

SEARCY

Yeah. (Laughter.)

SACHS

I’m particularly frustrated that they’re illegal.

SEARCY

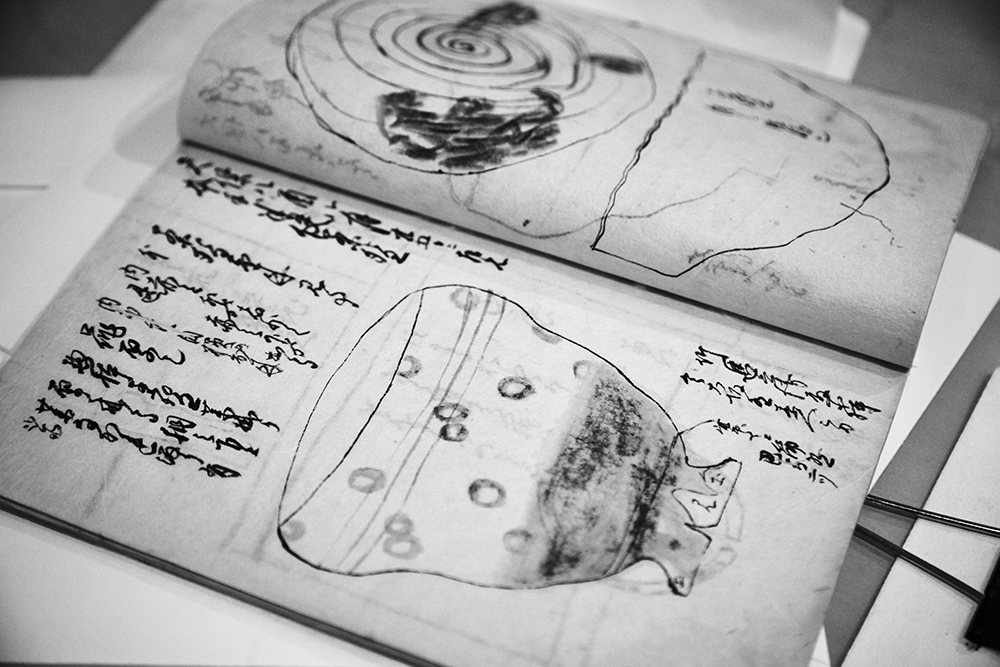

Well, they’re not in Texas anymore. You can carry ’em … of course you can carry bazookas in Texas, for that matter. (More teaware in an adjoining room. Perusal of a nineteenth century Japanese tea journal. Preparations to leave.)

SACHS

Thank you.

SEARCY

Yeah, well thank you for coming by. Oh, just one more thing (retrieving an old riveted aluminum suitcase and placing it on the bed). This is my only serious rocket, although it’s a little bit silly—it’s only a little bit silly. I mean it’s not philosophical like yours—but it’s kinda (opening the suitcase to reveal swoopy-finned silver rocket nested in green foam along with gray plastic fuel canister and yellow launch control device).

SACHS

Ooh. Wow. Is that the one you were telling me about?

SEARCY

Yeah—this is the finest of the Friedrich Schmiedl Rocket Society production. (Laughing) I think it’s got all the appropriate stamping—oh yeah, there’s the date and all the stuff.

SACHS

And so you put the sugar and potassium chloride (actually nitrate) in here?

SEARCY

Yeah, everything unscrews. It’s not the sort of thing you want to get on the airline with, although I was able to get on the airline with a much larger and more dangerous-looking one that I took to Black Rock Desert in Nevada in 1990. What you got in there? (imitating Texas drawl of ticket agent). Oh it’s just a rocket. Oh, okay, uh, yeah I guess it’s okay—what do you think? Yeah I guess its okay, just go ahead.” (Laughter.) Those were the days. But this one, now I’m not so sure I want to fire it anymore. I’ve had it for so long.

SACHS

Oh, it will be so much nicer when it’s all dented up and stuff.

SEARCY

It would be! It would be, but I’m afraid it’s going to come down through a cow. I was going to shoot it in West Texas but couldn’t find a rancher who was willing to endanger his cows.

SACHS

(Holding the rocket horizontally) I think it’s going to come down like this.

SEARCY

Nope. I’ve checked the center of pressure. I know how it’s going to come down.

SACHS

So, why do you think it’s gonna … (silent balancing and contemplation).

SEARCY

(In stupid Russian accent again) Eez no center of gravity. Eez center of pressure.

SACHS

How does that work, how does that work? Explain to me. ’Splain me.

SEARCY

Well, you, uh—this is how I do it.

SACHS

Yeah, yeah.

SEARCY

You’ve already put too much weight back here—this thing (the machined stainless steel exhaust nozzle) is very heavy, heavier than I intended. So the center of pressure is a function of aerodynamics, so tie a string around it (at the center of gravity) you know, tape it, and swing it around and see which way it faces.

SACHS

So it will come down through a cow.

SEARCY

Yeah, it’ll come …

SACHS

I mean, the worst case scenario, the most expensive cow in the area.

SEARCY

I like cows. I don’t want to hurt it. I’d feel terrible. It might take days to die. Could be a performance piece, I guess.

SACHS

And also—what about you?

SEARCY

Well, what are the odds, if you stand right at the launching pad? What are the odds?

SACHS

Well, there’s Murphy’s Law.

SEARCY

But that’s not a real law. Murphy just made that up. Because he was bitter.

SACHS

But I guess if you have a helmet …

All black-and-white photographs are by Peter Salisbury

David Searcy graduated SMU with a BFA in painting in 1969. He is the author of the novels Ordinary Horror and Last Things. Searcy’s first book of non-fiction, Shame and Wonder, is a series of interconnected ruminations about life, longing, obsession, the inner workings of various beautiful machines, and childhood dreams of space travel. He lives in Dallas, Texas.

Tom Sachs’s work has been included in many exhibitions in the U.S. and abroad, and has been collected by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Centre Georges Pompidou, San Francisco MOMA, and the Astrup Fearnley Museet for Moderne Kunst, Oslo. Major solo exhibitions include SITE Santa Fe (1999), the Bohen Foundation, New York (2002), Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin (2003), Astrup Fearnley Museet for Moderne Kunst, Oslo, and Fondazione Prada, Milan (2006), Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles (2007), Lever House, New York (2008), Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT (2009), Park Avenue Armory, New York (2012), The Noguchi Museum, New York (2016), Brooklyn Museum, New York (2016), Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco (2016). Sachs lives and works in New York.

from The Paris Review https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/01/08/tom-sachs-and-david-searcy-japanese-tea-rockets-and-switchblades/

Comments

Post a Comment