Frances Lee Glessner, Kitchen, from The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death (courtesy of Benrubi Gallery and Monacelli Press.)

Homicide. Suicide by hanging. A great deal of drinking, mainly of whiskey, mainly by men. Blood pooled on the floor. Chairs overturned. Many weapons: guns and knives and ropes. “Burned Cabin,” where a burned skeleton is barely visible, “Dark Bathroom,” which contains a dead woman in a bathtub beside an empty liquor bottle, and “Unpapered Bedroom,” in a boarding house where an “unknown woman” has been found dead.

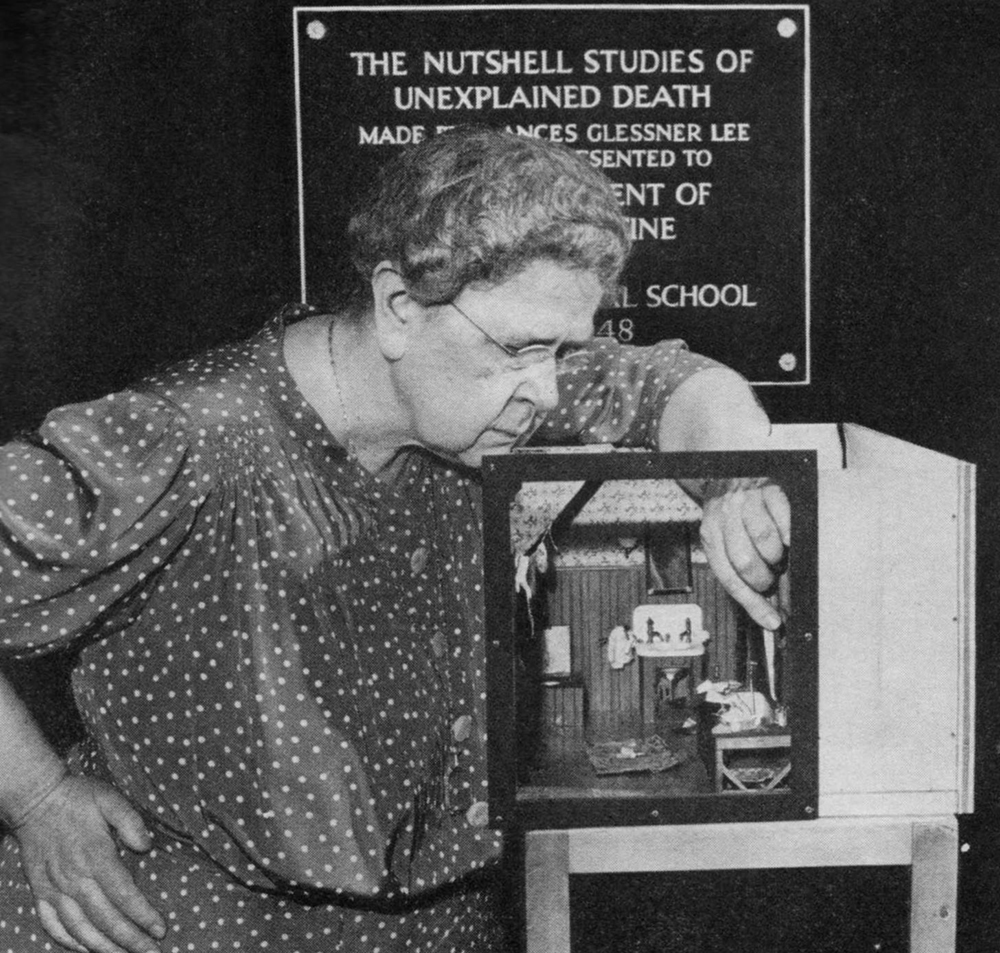

In Frances Glessner Lee’s dioramas, the world is harsh and dark and dangerous to women. “The Nutshell Series of Unexplained Death,” her series of nineteen models from the 1950s, are all crime scenes. Glessner Lee built the dioramas, she said, “to convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell.”

Frances Glessner Lee with her Nutshell diorama, Dark Bathroom. Image courtesy Glessner House Museum, Chicago, IL

The word “nutshell” might strike us as childish, cute, even sweet. Indeed, the dioramas are rendered exactly on the 1:12 scale of traditional dollhouses. Inside the dioramas, along with the weapons and bodies, are round crocheted rugs and neatly set kitchen tables with tiny flowered plates and coffee cups. And, like the Nuremberg Kitchens from 17th century Europe — miniature houses designed to show affluent young girls how to run a household — Lee’s dioramas also had a pedagogical purpose: they were used to train police officers and detectives.

Yet there is nothing traditional about Frances Glessner Lee or her work. Her dioramas are deeply subversive. And they are ideal viewing for our current moment.

Frances Glessner Lee at work on the Nutshells in the early 1940s. Image courtesy Glessner House Museum, Chicago, Il.

Most of the dead in Frances Glessner Lee’s models are women killed in their own homes. (Seventeen of the nineteen dioramas are set in homes, and eleven depict dead women.) Women fallen down stairs. Women with rope burns on their necks. Women murdered in the of act of packing to leave, dresser drawers and suitcases splayed open to reveal miniature clothes.

Although I have spent several years researching and writing a book on dollhouses and miniatures, I never expected to see the nutshells unless I began a new career in law enforcement. The dioramas are generally kept in Baltimore at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner.

But this fall, the first public exhibit of Glessner Lee’s work, “Murder Is Her Hobby,” took place at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. On my several visits, I stood in crowds of people, in the dark, sharing small flashlights (one provided for each diorama). Everyone was trying to solve the crimes. The gallery buzzed with voices. A sign noted, “Photography Encouraged.” The first time I visited, as I scribbled in my notebook at the entrance, a woman beside me whispered to her friend, “Where’s your paper to write down the clues like her?”

Frances Glessner Lee began designing and building the dioramas when she was sixty-five and worked on the project for ten years. Her life (1878-1962) spanned two world wars, women finally getting the right to vote, and the beginnings of second-wave feminism. Corinne May Botz, artist and author of the first and only scholarly book about Glessner Lee, the gorgeously photographed and beautifully written, The Nutshell Series of Unexplained Death (2004), gives a feminist reading of Glessner Lee’s dioramas. She explained to me that “Lee was able to redefine her own role in society late in life. The Nutshell Studies gave her a voice in the world and allowed her to advance in the male dominated field of crime scene investigation. The Nutshells can be viewed as precursors to the women’s movement because they depict the isolation of women in the home and expose the violence that originates and is enacted there.”

As is the case with so many women involved in miniatures in the early and mid twentieth century, Glessner Lee’s husband apparently did not like her miniature work. As one article attests, “The couple had three children and at first appeared happy, but Glessner Lee eventually received a divorce. Their son attributed the failed marriage partly to her “creative urge coupled with high manual dexterity—the desire to make things—which [Lee] did not share.” Again and again, I’ve seen, in my research on female miniature artists, a disapproving husband often tries to thwart a wife’s career in miniatures.

In addition, as I’ve found in all the writing about the most prominent American miniaturists of the twentieth century (Narcissa Thorne, Colleen Moore, Florine and Ettie Stettheimer), most pieces about Glessner Lee emphasize her upper-class background. Her wealth afforded her the time to make the dioramas, and she later endowed the Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard, but her status as an affluent woman also leads to an odd kind of judgment about her. A recent New York Times review of the Renwick Gallery show refers to her as a “rich, frustrated woman.”

Much is also made of her lack of education. Glessner Lee’s brother had been sent to Harvard, but Glessner Lee did not attend college. This did not stop her from inventing an entirely new teaching tool for police investigation. In 1942, Glessner Lee was named a captain in the New Hampshire State Police force, with no formal forensic training. In a letter quoted in Corinne May Botz’s book, Glessner Lee explains her interest in constructing the dioramas and her fascination with the field of legal medicine: “When an opportunity came to me to start something new in the medical line. I was delighted to take it on. As a girl, I was deeply interested in medicine and nursing and would have enjoyed taking training in either one.” She was a mother and a grandmother—in fact, in much of the writing about her dioramas her status as a grandmother is insisted upon. As if grandmothers should not have anything to do with murder and violence, should not invent and build models of crime scenes?

To me, her being a grandmother—and a mother, and a daughter, and a sister and a wife and a woman living in the world—gives her all the authority she will ever need to depict violence against women. Though it was made in the 1950s, Glessner Lee’s work feels decidedly – and disturbingly — contemporary.

Part of this is due to the dolls in her dioramas. The inclusion of bodies in a miniature scene is a radical choice. While most twentieth century and contemporary miniature artists keep their scenes deliberately empty, Glessner Lee puts the body at the center. The dead women, six inches tall, lie in the bathtub, on the steps, on the floor, in their beds. Always, it is the female body that is at the center.

This is what strikes me as the most contemporary and urgent element of the dioramas. Frances Glessner Lee is telling us that women’s bodies are in danger, over and over.

In the diorama titled “Kitchen,” a woman lies on the floor, face up, next to a refrigerator, which is open. A metal ice cube tray is beside her face. In the background, a pie is slid halfway out of the oven. Potatoes are partially peeled in the sink. A knife rests on a stack of linens. An iron waits on a wooden ironing board. The question is: which of the domestic objects in this scene has been used to kill the woman?

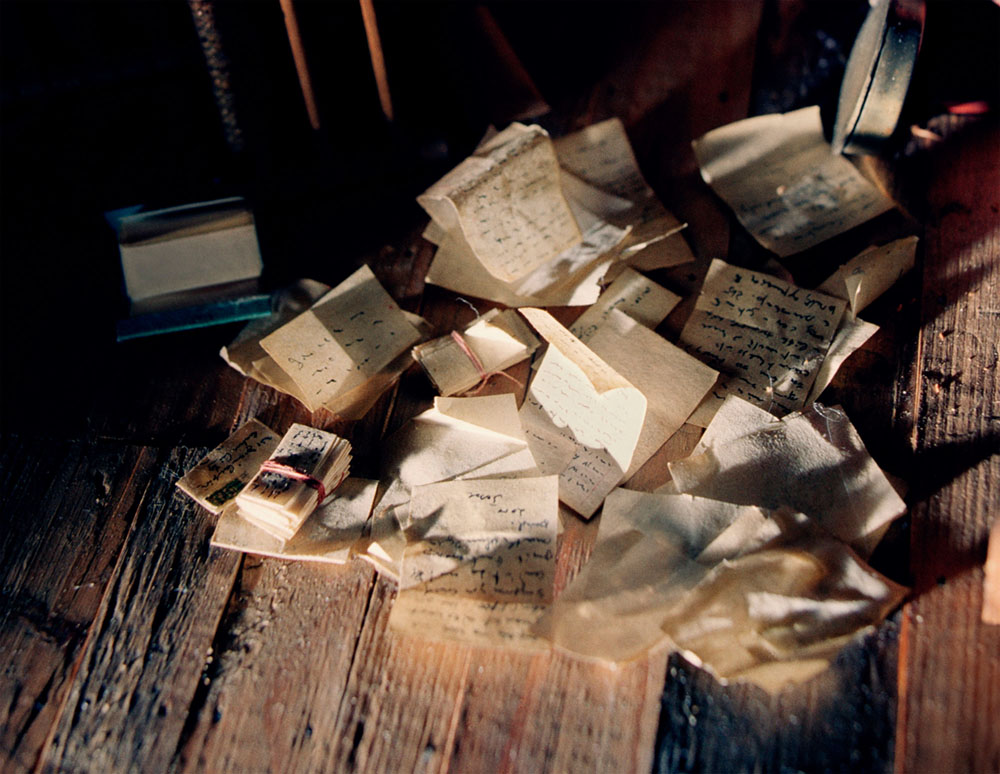

“Attic” asks us to consider both suicide and murder. An elderly woman is dead by hanging, an overturned chair below her body. Her eyes are painted open; her face might be bruised. On her feet are tiny darned socks, one shoe slipping off. Packets of opened letters, and a series of odd objects surround her, including a china doll and a gramophone. Did she kill herself? Or did someone stage this woman’s death? And why?

Frances Lee Glessner, Attic, from The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death (courtesy of Benrubi Gallery and Monacelli Press.)

Frances Lee Glessner, Attic (letters), from The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death (courtesy of Benrubi Gallery and Monacelli Press.)

In “Three Room Dwelling,” the largest of the dioramas, an entire family is dead. The viewer looks down at the scene of a roofless house to find a husband face down on the floor, a wife dead in her bed and a baby with a bloody face dead in a white crib. The floor of each room is splotched with blood. A rifle lies on the kitchen tiles. The table is set for breakfast and included a highchair. Did an intruder kill the family? Did the husband murder everyone then kill himself?

When the show at the Smithsonian closes, the nutshells will return to Baltimore. They are still used to instruct homicide detectives. In the past few years, several women have produced new work about Glessner Lee and the Nutshell series: from Carol Guess’s poetry collection Doll Studies: Forensics to the play in progress, Nutshell, by C. Denby Swanson to Susan Marks’ 2017 film ‘Murder in a Nutshell: The Frances Glessner Lee Story.

Glessner Lee’s work lives on. The dioramas could be teaching tools for all of us. As Corinne May Botz told me, “Just like in the models, in the US women are much more likely to be killed by intimate partners than by strangers. The grim reality is that the world is full of violence. The models are a reminder that domestic space can be safe as well as terrifying.”

It was not lost on me that I saw Frances Glessner Lee’s work—and the bodies of all these women and the gendered violence she makes explicit— at a gallery just across the street from the White House.

Nicole Cooley is the author of seven books of poems and is currently completing a non-fiction work titled, My Dollhouse, Myself: Miniature Histories. She is the director of the MFA Program at Queens College-CUNY.

from The Paris Review http://ift.tt/2EhMCDD

Comments

Post a Comment