Now out in its fiftieth-anniversary edition, Jill Freedman’s Resurrection City documented the culmination of the Poor People’s Campaign of 1968, organized by Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and carried out under the leadership of Ralph Abernathy in the wake of Dr King’s assassination. Three thousand people set up camp for six weeks in a makeshift town that was dubbed Resurrection City, and participated in daily protests. Freedman lived in the encampment for its entire six weeks, photographing the residents, their daily lives, their protests and their eventual eviction.

I knew I had to shoot the Poor Peoples Campaign when they murdered Martin Luther King, Jr. I had to see what was happening, to record it and be part of it, I felt so bad. Besides, it sounded too good to miss.

So I went and had one of the times of my life, and this is my trip. And I never realized how much it had become a part of me until I was writing this and saying we and us and feeling homesick.

Which is what Resurrection City was all about.

Of course, it was old stuff from the start. Another nonviolent demonstration. Another march on Washington. Another army camping, calling on a government that acts like the telephone company.

Even poverty is ancient history. Always have been poor people, still are, always will be. Because governments are run by ambitious men of no imagination. Whose priorities are so twisted that they burn food while people starve. And we let them. So that history doesn’t change much but the names. Nothing protects the innocent.

And no news is new.

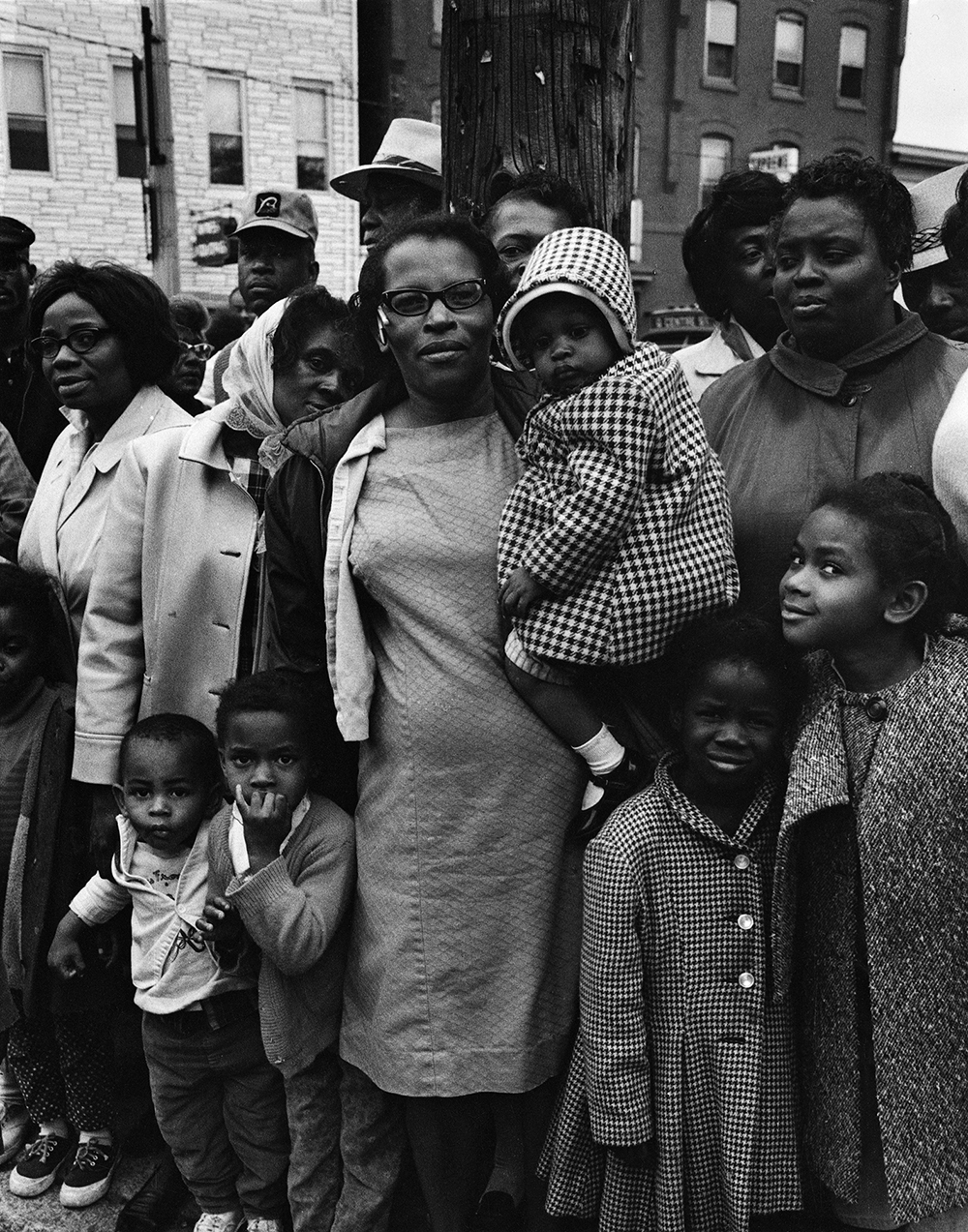

Jill Freedman. Residents watch Poor People’s Campaign, Northeast caravan people marching through their town. 6 days of caravan, 6 towns, marching, rally. Some joined us, we picked up new people at each stop. The Black community fed us and we slept in their churches, 1968

Martin asked the Indians if we could come stay on their land awhile. They said sure and so, like earlier pioneers, we went to Washington to build a city. Long covered Greyhound wagon trains, full to bursting with the tired, the hungry, the poor, buddle and yearning to breathe free. A new Bonus Army, coming to collect on the dues we’d been paying all these years. Coming to take what was ours.

I went down on the Northeast Caravan, which started in New England but picked most of us up in New York the second day. From New York we went to Newark, then Trenton, Wilmington, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, taking new people with us each morning.

It was exciting, counting ourselves going around curves, rolling into a new city each day. People coming to meet us. “Join us, join us,” we’d shout. Many would. Until it seemed as though the whole town were marching, singing together.

Jill Freedman. Shanties being built in Resurrection City, Poor People’s Campaign, Washington, D.C., May 13, 1968

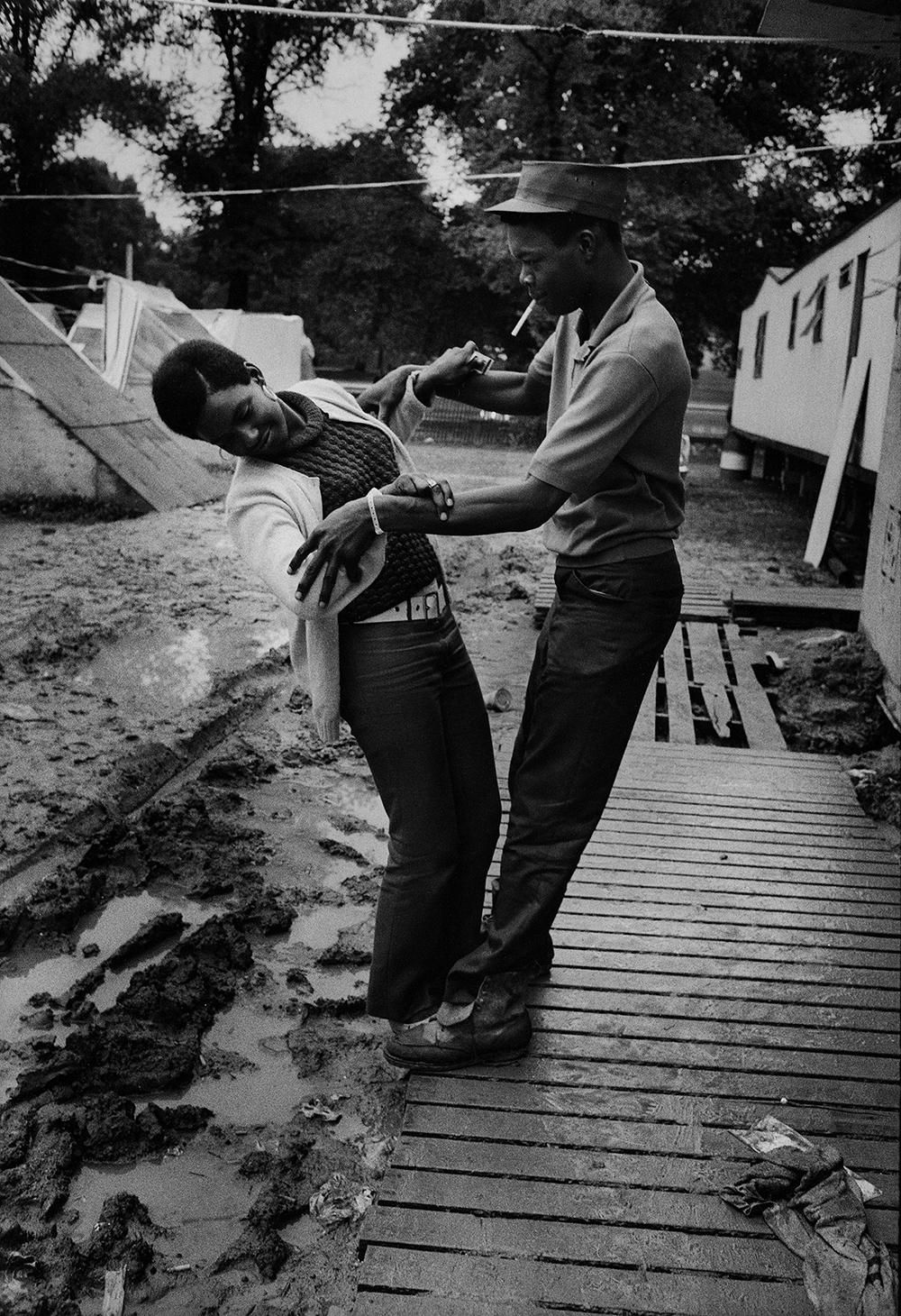

Jill Freedman. Couple playing on muddy walkway, Resurrection City, Poor People’s Campaign, Washington, D.C., 1968

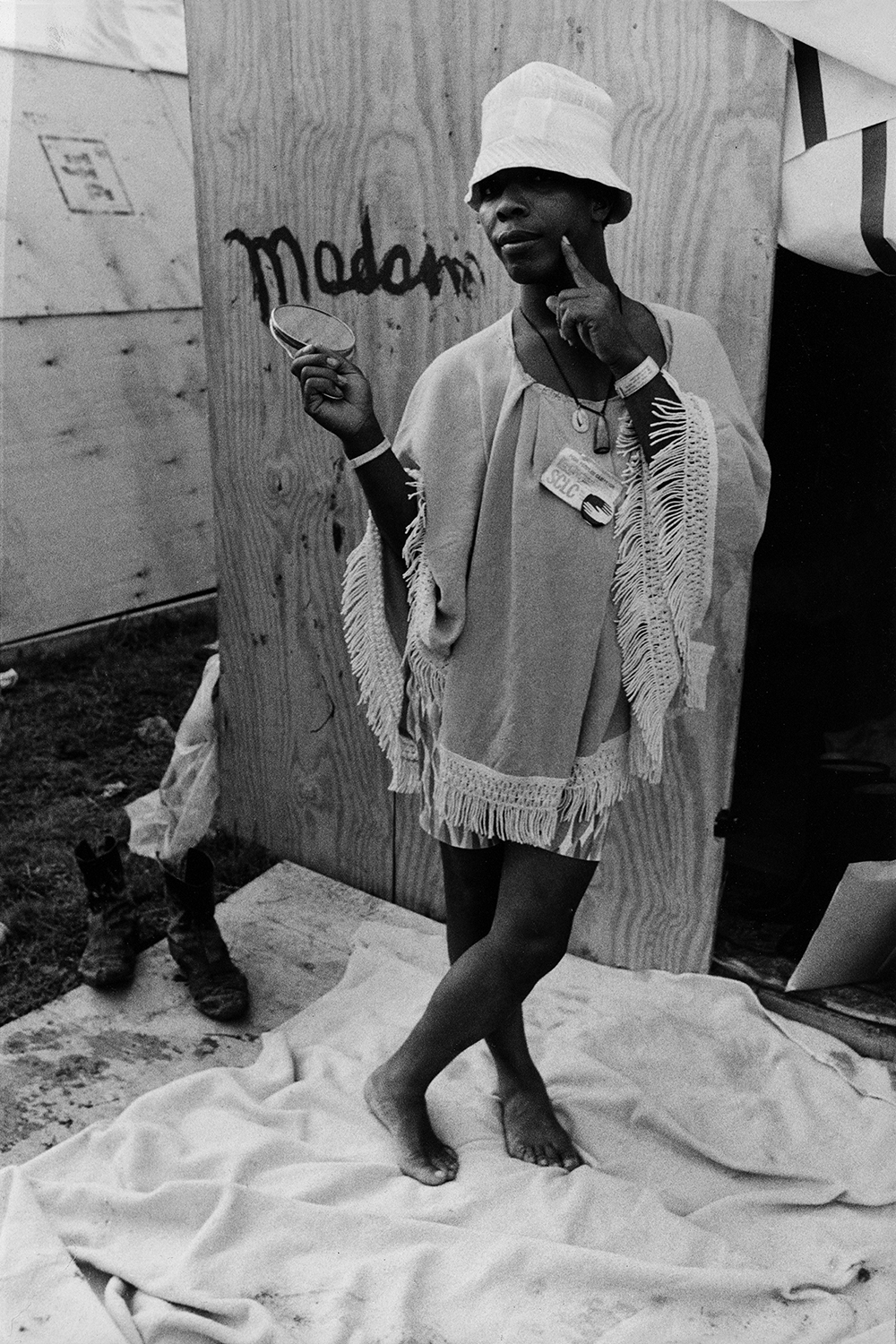

If you forget about things like traffic lights and dress shops and cops, Resurrection City was pretty much just another city. Crowded. Hungry. Dirty. Gossipy. Beautiful. It was the world, squeezed between flimsy snow fences and stinking humanity. There were people there who’d give you the shirt off their backs, and others who’d kill you for yours. And every type in between. Just a city.

Jill Freedman. Little Joe at the free clothing swap in Resurrection City, Poor People’s Campaign, Washington D.C., 1968

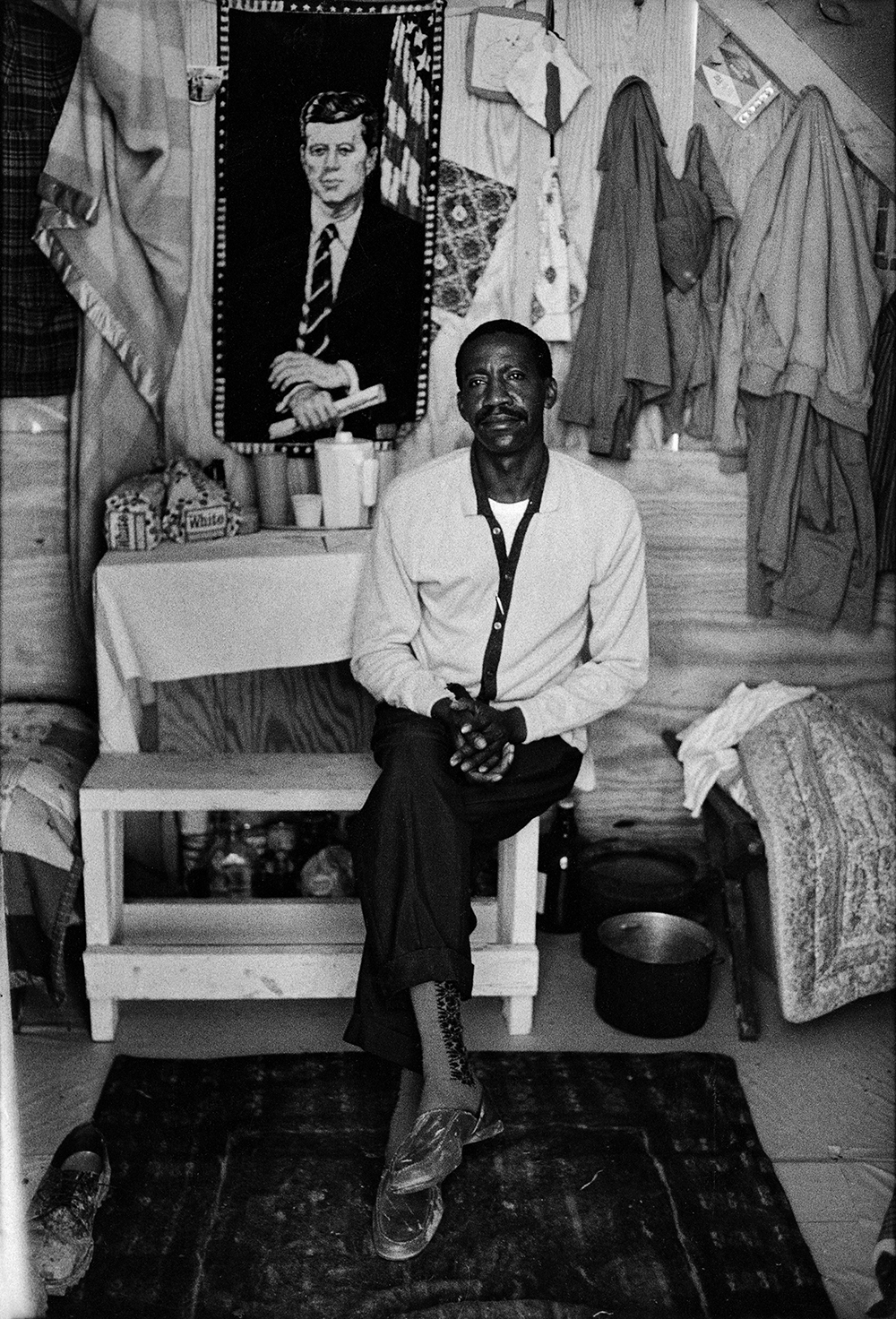

Jill Freedman. Man in front of tapestry of JFK inside his temporary home in Resurrection City, Poor People’s Campaign, Washington, D.C., 1968

Talk about poor.

Some of those people raised their whole standard of living just by moving in. For the first time in their lives, they knew their kids would eat every day. Not only that, they thought they were eating good. Soggy cabbage leaves and baloney sandwiches. Even the houses were better than what they’d come from. Electric lights, clean new wood, and—believe it!—enough beds for everyone. This mudhole was a paradise, that’s how poor some of these people were.

And it showed. In the wizened children and winos and junkies and schizos, casualties of the war for survival, their eyes broken as their shoes. And in the others, wearing their faces like medals. Tough, proud, dignified faces.

I’ve seen poorer people commuting to Wall Street.

Much poorer.

But not as hungry.

Jill Freedman. Boys playing in the mud after days of rain, Resurrection City, Poor People’s Campaign, Washington, D.C., 1968

Jill Freedman. Demonstrator with Dr. King sign at the Puerto Rican Day March, Poor People’s Campaign, Washington D.C., 1968

Poverty and war are death. Resurrection City was lobbying for life. The Vietnam War was costing us 80 million dollars a day. $3.8 million an hour just to kill people. Some of them our own kids. We thought this was impractical. So when a small group of men and women came to D.C. to burn draft cards, some Soul City people were there to support them.

This was the first time that women burned draft cards, and the punishment was the same as for men. $10,000 and five years in jail. For trying to stop a dirty war they hated. Maybe wondering whether anything they did would matter a damn. But unable to give up hope.

During the interviews, two reporters were unmasked as somebody’s secret agents and skulked away. Men and women risk five years of freedom, and these cornballs play spy.

The ceremony was simple. Each woman traded her young man a flower for his card. Calling out her name and his, she put it to a torch.

One by one, taking turns until the last card was burned and everyone joined hands and sang we shall overcome and it was over. Even the camera crews were quiet.

When BANG like an orgy at a church bazaar come the American cops’ Pavlovian response to peace. Twirling their patriotic clubs like drum majorettes, they knocked people around until they found the one they wanted and threw him into the wagon. A draft resister who, while somehow having the last word, revealed that Dream City had lost a son. Another family for peace.

Send a poet to the moon.

Give peace a chance.

Jill Freedman. Madam, Outside of her Shack, Resurrection City, Poor People’s Campaign, Washington D.C., 1968

The last day was a formality.

At 9:00 a bullhorn gave us a generous half-hour to pack up out city. Anyone remaining longer would be arrested on the spot. Everyone else could choose between being arrested up at the Capitol Building, or leaving.

And so it went, smooth as a politician, the people singing and joking as they filed themselves into the transports.

The rest of us couldn’t see it.

So we split.

Jill Freedman. Protest sign in a pile of trash on the last day of Resurrection City, Poor Peoples Campaign, Washington D.C., 1968, June 24, 1968

Jill Freedman is a New York City documentary photographer.

Excerpted from Resurrection City, 1968. Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York.

from The Paris Review http://ift.tt/2Ed4oc4

Comments

Post a Comment