I spent my first twenty-three years on this planet living in the same apartment building in the Bronx. I felt ownership over those gum-stained concrete blocks. I dreamed of scattering my ashes on them when I died, like Miguel Piñero scattered his around the Lower East Side. (I still might.)

Then, two years ago, when I was twenty-five, I left New York. I left because I was tired. I started working at thirteen to contribute to my household. I busted my ass in public schools, got a scholarship to a Catholic high school, and graduated college with an Ivy League degree. Despite all this, I still lived check to check, just like everyone else I knew. I wanted to do the things my single mom had never had the chance to, like own property or save for retirement. But I saw the money flowing into New York City. I saw neglected neighborhoods regurgitate cocktail bars and cycling studios. I saw the rents skyrocket as fast as the property values. I knew, at best, I could only hope to maintain. I was fucking tired of maintaining.

When I first got to South Florida, I did what most New Yorkers do when they leave: I constantly compared my new home to my old one. I drove past deserted sun-bleached streets and searched for pedestrians. I grew tired of Latin food and longed for Indian or Vietnamese options. Mostly, I missed the people: the looks they served, their affection for breaking out in dance and song, their displays of affection, their catty arguments, their plethora of languages, the way energy pulsated out of their bodies with each step on the pavement. Eventually, I learned to adopt the crazed stare drivers here give to anyone actually walking. I found an Indian spot. I still miss New York City people, though.

Thank God for Andre D. Wagner. There are many Instagram accounts I follow for a fix, but his is one of the best. Born and raised in Omaha, Nebraska, Wagner moved to New York in 2011 after completing his undergraduate degree at a small university in Iowa, where he was a guard on the basketball team. He came to New York hoping for a career in social work, but, after finding a job in a photo studio in Manhattan, fell in love with the medium. Since, he has put together an impressive portfolio of freelance work—his images documenting African American and immigrant communities in New York City regularly grace the pages of the New York Times.

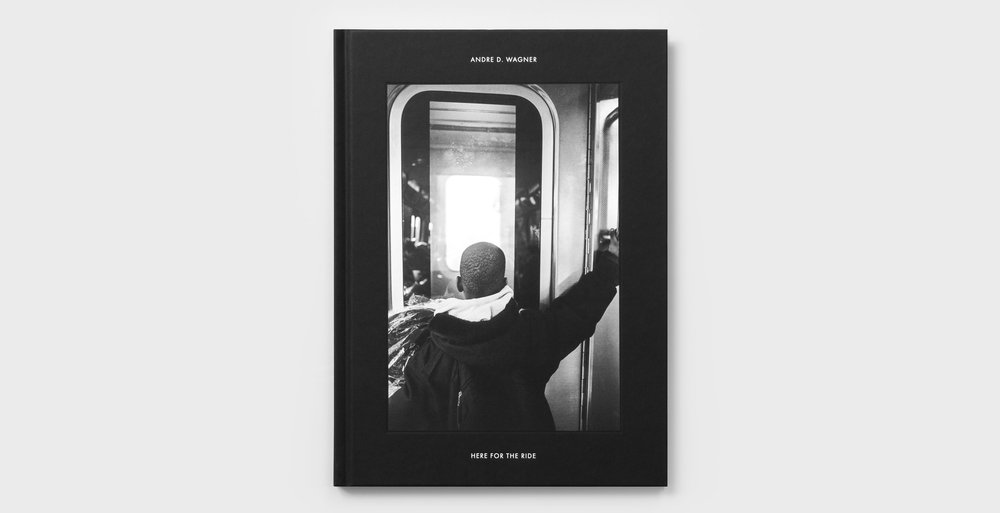

Late last year, Wagner released his first book-length collection of photography, Here for the Ride. When I saw the cover photo, a young boy staring out the very last car of the train, barely tall enough to grip the handle bar, I saw myself as a young boy riding the 4 train home from middle school in the South Bronx. I remembered the rattling elevated train tracks and how they wound through buildings. Remembered how I’d stare from the same scuffed windows at rooftops slathered in graffiti, in awe of how mere mortals made art that high.

Wagner’s book is a compilation of sixty-two photographs taken on the subway over three years. He began work on it, unknowingly, in 2013, after he moving to Bushwick. He still had his job at the photo studio in Manhattan and made the long commute back and forth each day, shooting to pass time. The book coalesced, then the title. “I was literally there for the ride,” he said in a phone interview this month.

Like all of his work, the book is shot on film (Wagner built his own home photo studio from scratch and methodically creates his own prints). Flip through and find the familiar exasperated expressions staring out the windows of packed trains, or necks craned down to the ends of platforms, willing trains to arrive. A commotion of bodies flowing up and down the stairs, oblivious of one another. Bodies folded into each other and themselves, turning shoulders and guard rails into pillows.

In other photos, you’ll find the diversity the New York City subway engenders—the train car an equalizer in a city that often feels like two different ones depending on the stop. In one image, two young black children lean against each other with silent, despondent faces. Next to them sit two giggling white girls their age. The sliver of space between them is a visual representation of the feeling I recall riding the train as a fifteen-year-old.

That summer, I’d gotten my first job in Manhattan as an office assistant at a nonprofit in Midtown. Each day, on the forty-five-minute ride south, I watched the train morph from the mostly brown and black people who got on in the Bronx, feverishly sipping coffee and already tired, to the mostly white faces that got on after Harlem. I stared at these new arrivals and wondered where they purchased their winged-tipped shoes. I eyed their leather briefcases and purses, pocket squares, pinstriped suits and hemmed skirts and wondered what their apartments looked like and if they shared them with roaches and mice, too. On the way home each evening, I watched the performance in reverse. I learned that if I stood in front of one of these people in the packed car, the odds were I’d have a seat to rest my legs, which were tired from pushing boxes on a dolly back and forth to the UPS store, by Eighty-Sixth Street.

Wagner says this sort of fluid movement between communities and cultures and the ways in which they clash underground is central to his book. “What does it mean to be a black man moving through these different spaces?” he asks. “What does it mean to live in a community like Bushwick and travel to Manhattan?” Many of his photos attempt to answer these questions. To me, some of the most poignant are the images of middle school and high school boys traveling in packs, claiming subway cars and stations as their own for a few hours after school, before their parents come home from work.

“Kids have so much agency in the subway,” says Wagner. “They have their own community in a way. That was important for me to capture.”

I knew that agency. By the third grade, I walked to and from school on my own, and by the fifth grade, I took my younger sisters by the hand with me. By middle school, I rode trains and buses into one of the more dangerous neighborhoods in the South Bronx, and by high school, I took them to underlit sections of Brooklyn to drink and smoke at warehouse parties.

One photo, of five posturing boys staring straight into Wagner’s lens, teleports me back to the days I was just like them. With seemingly endless hours to kill, my friends and I took trains and buses to out-of-the-way pizza places or chicken spots in the Bronx, killing time in booths, sharing one soda between two or three of us. We killed more time on subway benches, letting the trains pass as we talked about the Mets or the Yankees, or the girls in class we were too afraid to speak to. When we’d finally board, we crowded around each other, as the boys in Wagner’s photo do, gripping the pole, feeling stronger and brasher in our number. We joked, or cut each other’s ass, as we’d say, affectionately, laughing louder than we needed to. And in the gang-plagued days of the early 2000s, when you still had to be mindful about what color your T-shirt was, we paused to shift our eyes every so often to size up who was around us.

Wagner counts photographers such as Roy DeCarava and Garry Winogrand among his influences. When he came to New York, he pored over their books, forgoing a traditional education in photography for a self-guided approach. He spent hours and hours walking the streets and coming home to process what he shot slowly and methodically. It is this careful approach that, in a city full of street photographers, makes his eye stand out. His images beckon to be revisited. “Photography has this nostalgia component to it. With time, good work always gets better because people want to look back,” says Wagner.

Everyone who has set foot in New York has their own stories of the subway. Part of the charm is the experience, one that always feels personal and distinct, with each ride in the car. Wagner’s photographs are special in that they encapsulate a multitude of experiences, allowing viewers, even those who live thousands of miles away and no longer ride the trains as often as they used to, to see themselves.

Andrew Boryga is a writer whose previous nonfiction has appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Times, and The Atlantic. He is currently at work on a novel.

from The Paris Review http://ift.tt/2oq1uWm

Comments

Post a Comment