In December, it seemed like all anyone did was go to the movies and cry. My friends sobbed over Call Me by Your Name, with its dizzyingly lush depictions of queer desire; over the women leading Star Wars’ resistance; and over a girl who called herself Lady Bird. At most of these, I cried, too, but the outpouring of feeling around Lady Bird made me feel sad, and a little isolated.

Lady Bird is Greta Gerwig’s solo directorial debut; it follows the titular Lady (née Christine)’s struggles over the course of her senior year of high school. In the weeks after its release, my Twitter timeline overflowed with women who related to its particulars: who had grown up in stifling suburbs or spent their teen years singing along to cast recordings in overstuffed minivans. We had all, it seemed, written boys’ names onto our notebooks and sneaker rubber and wrists. We had all fought bitterly, epically, endlessly, with our moms.

Every time I saw a woman opine that Lady Bird was the future of film, an unprecedented and astonishing event, I wished we were somewhere other than on Twitter, where everything sounds like shouting. I wanted to be able to say, gently, There is actually a very rich tradition of this kind of writing available to you. You just have to know that you want it. And then you have to know where to find it.

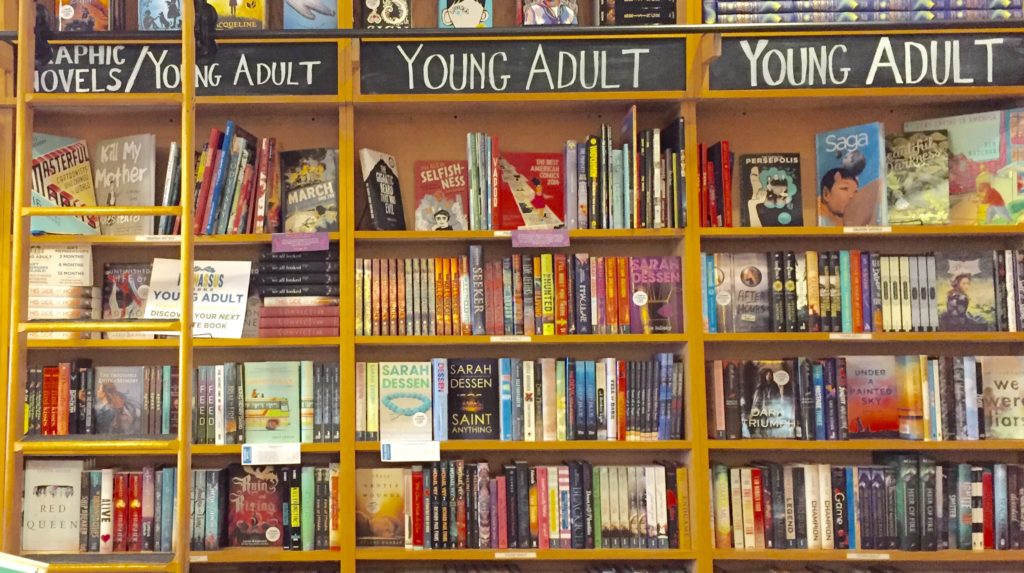

Where to find it, of course, is on the young-adult shelves of every bookstore in America, which are piled high and bright with novels written by people—many of us women—who care deeply about how and why we tell the stories of teenage girlhood. We’ve been trying to do it carefully and beautifully and well for the space of our careers.

I liked Lady Bird, but I didn’t love it—but then, I didn’t feel that I had to. I live surrounded by a surfeit of stories like that one. Lady Bird lacked the particular chemistry that makes books like Brenna Yovanoff’s Places No One Knows or my friend Maurene Goo’s forthcoming The Way You Make Me Feel so shockingly, achingly familiar: that electric recognition of yourself in someone else’s art. The feeling that without even knowing it, the artist has made space for you. They have called you home.

In Goo’s case, that sense of home was literal: her evocations of a Los Angeles girlhood made me ache with recognition of my city and my self.

My relationship to Yovanoff’s heroine, Waverly, was a little more interior. Waverly seems at first like a straightforward, straight A, good girl, but Waverly is obsessed with the idea that everyone else is good, and that it’s only her who has to work so hard to pretend to be.

Waverly reminded me how difficult it is to be bright and intense and aggressive and a little manipulative, sometimes, when you are also trying to be a girl. When you don’t yet understand that a girl can be—is—only exactly what you are. It was books like those that made me want to write YA myself. Long before my own two YA novels were published, I haunted the teen-fiction aisles of bookstores. I’d been too proud for this kind of fiction when I was a teenager; now, those novels help me see, understand, and reframe the myths I held about myself—the first one being that a teenage girl was a dumb, embarrassing thing to be. They make me feel cared for, because they make me, in all of my unpleasant particulars, feel seen.

I’ve heard it suggested that looking for yourself in fiction is an unsophisticated way to read. But it can be emotionally authentic—who doesn’t want to see herself reflected in her culture?— and more importantly, it can be fun. The true worth of reading for pleasure is often undervalued, especially among women. As Jaime Green recently argued in a piece about romance novels for Buzzfeed, “the idea of women reading books that are escapist delights instead of ‘bettering’ themselves via the male-adjudicated canon or, honestly, doing housework or tending to their kids [is subversive]. Romance novels are political because of, not despite, the fact that they are usually really fucking fun.” I’d argue that the same is true of YA.

And like romance novels, YA has a significant marketing problem: the category has been cast as silly and shallow in myriad bad-faith op-eds. And yes, the biggest blockbusters of the genre won’t resonate with a reader who’s mostly drawn to literary fiction. But then, no one dismisses literary fiction on the basis of what’s sitting atop the New York Times’ best-seller list. It’s understood that what’s broadly popular doesn’t represent the depth of what’s available.

YA is not a reading level, and it’s not a genre, either. It’s a marketing category, and all kinds of things end up shepherded onto its shelves. Robin Wasserman wrote young-adult novels before her adult debut, Girls on Fire; Naomi Novik’s Uprooted is double-shelved in YA and among fantasy novels for adults. I know the arbitrary nature of these categories firsthand: when I was looking for an agent, shopping the book that would become A Song to Take the World Apart around, I found readers frustratingly and precisely divided. Agents who represented literary fiction felt certain it was YA; young-adult agents wondered whether I had considered trying to sell it as literary fiction.

Not all YA will work for every reader, but to dismiss the entire category may be to dismiss the very book you didn’t know you needed. After all, YA may be aimed at teens in theory, but it’s almost always being written by adults with an intimate experience of teenage girlhoods. We are speaking, on some level, to ourselves, and to our past selves. Just like Gerwig with Lady Bird.

If you were interested in Lady Bird, I promise you, you are interested in YA. You might be interested in the magical realism of Samantha Mabry’s National Book Award–nominated All the Wind in the World, or the twisted fairy tales of Melissa Albert’s The Hazel Wood. Katie Coyle’s Vivian Apple books are tender about friendship and sharp about politics. Kate Hart’s After the Fall has a complicated mother figure and a midsize city and a girl who wants more for herself—without more necessarily being conflated with expensive private college and life in a big coastal city.

Lady Bird posits that paying real, careful attention to something is closely akin to loving it. In a moment that demands that we expend so much of our focus on things that are painful and difficult, even I could feel the reprieve of it: how wonderful it was to be given the gift of Gerwig’s alert gaze. How unusual to allow a teenage girl, and, in turn, our own teenage selves, to be the center of our attention.

I am thrilled that Lady Bird reminded women how it feels to be seen. I only hope that it will also encourage them to look for more reminders. There are many unexpected, uncool, too-earnest unabashedly female things to pay attention to, and to love as well.

Zan Romanoff is a full-time freelance writer and the author of two young adult novels, A Song to Take the World Apart and Grace and the Fever.

from The Paris Review http://ift.tt/2E9dlyR

Comments

Post a Comment