Willa Cather was not a flashy stylist, and though she was ambitious in her work, she did not attach it to a publicity-worthy life like some of her contemporaries, such as Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Cather’s first book of poetry came out in 1903, when she was twenty-nine; her first book of stories followed a couple years later, when she was thirty-one. Her last novel appeared in 1940, and a volume of three more stories was published in 1948, shortly after she died. Forty-five years is a long career for a novelist, but she possessed an intensity of observation and a curiosity about human psychology, especially as it relates to nature, that never waned. My Ántonia is one of her best-loved books, and it displays all the characteristics that make Cather both elusive and fascinating even as it depicts a world that vanished almost as soon as the novel was published.

Willa Cather was born in an interesting spot in the mountains of Virginia, near Winchester, on the banks of a tributary of the Potomac, Back Creek. The family properties (one owned by her grandfather, another given to her father by her grandfather) were about ninety miles from Washington, D.C., and fifty miles from prosperous plantation regions like Loudon County. But—perhaps especially after the Civil War—it was difficult to make a living in the mountains and dangerous because of tuberculosis outbreaks, so Cather’s father and mother, Charles and Mary Virginia, took Willa and the other children (eventually there were seven in all) to rural Nebraska. After their first winter in the country, they settled in Red Cloud, a new town six miles north of the Kansas border and about halfway between the northwestern corner of Missouri and the northeastern corner of Colorado. Willa was about to turn ten. In Nebraska, the Cathers, immigrants from Virginia, immediately encountered a huge population of other immigrants from more distant and perhaps more romantic—to Willa—places: Norway, Sweden, France, Bohemia, Mexico. A sense of the world that compelled Cather for the rest of her life began to develop, a sense of the world that is deeply American, simultaneously local and exploratory, rustic and cosmopolitan.

Cather’s early prairie novels were published over the course of six years that were extremely eventful in American and world history—O Pioneers! in 1913, The Song of the Lark in 1915, and My Ántonia in 1918. She did not address the issues of World War I until her next novel, One of Ours, published in 1922. (It won the Pulitzer Prize.) But in all four works, the main characters—Alexandra, Thea, Ántonia, and Claude—wrestle with more or less the same question, maybe the essential question of the twentieth century: to stay or to go, and if so, how and why?

O Pioneers!, The Song of the Lark, and My Ántonia (and also the first half of One of Ours) are linked by place, not by character—unlike Émile Zola’s or Anthony Trollope’s series, Cather does not write about characters who are related to or know each other. As a result, once we have read the early novels, we feel as though we are watching the characters from a distance as they put their lives together and move across the landscape. Other prominent and bestselling authors in the first two decades of the twentieth century were looking at Europe and high society (Henry James, Edith Wharton) or the future (H. G. Wells) or the trials of the urban poor (Upton Sinclair, Winston Churchill—not the Winston Churchill, but a bestselling, now unknown novelist from St. Louis). Authors who wrote about the West wrote books like Zane Grey’s The Lone Star Ranger, disparaged by critics as unrealistic and unnecessarily violent. Cather, who began her career in magazine publishing, knew perfectly well what was popular and what was respected, but like Alexandra, Thea, and Ántonia, she was determined to go her own way. As a result, her novels stick in the reader’s mind as flickering memories of places we may never have seen with our own eyes.

O Pioneers! and The Song of the Lark are told from the omniscient point of view. O Pioneers! begins with a long shot of a snowstorm and a young boy crying because his kitten has gotten away from him; it then hones in on Alexandra, the protagonist, who will eventually, and almost by herself, develop the family farm. The Song of the Lark, which focuses on Thea, a child of eleven, begins with a visit from the town doctor, who makes a house call and discovers that Thea has pneumonia. We are asked to contemplate Thea through the lens of her family, not her landscape—her family and friends are what she must leave in order to achieve renown as a musician. For My Ántonia, Cather chose a more conversational first-person point of view—in the introduction, Cather recounts a chance encounter with an old acquaintance on a train across Iowa. They reminisce about a striking girl whom they both remember fondly. Cather wants to write about her, but Jim Burden, a lawyer in New York, has already set down his memories of Ántonia. He sends them to Cather, and his notes form the novel.

Jim is a stand-in for Cather’s own voice. In Red Cloud, Cather was old enough to remember Virginia and to observe the uniqueness of her new environment as well as the energy and hardships of the immigrants around her. She thrived in school and planned to be a doctor—she dissected frogs, kept her hair short, and even signed her name “William Cather.” After giving a celebrated high-school graduation speech, she went to college at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln. In her biography of Cather, Hermione Lee points out that Cather also felt a sense of constriction in Red Cloud and that her seesaw of ambition and constriction was common to writers who were growing up in small towns during the same time period, such as Sinclair Lewis, Sherwood Anderson, and Theodore Dreiser. Life at the end of the nineteenth century meant easy rail transportation, lots of magazines, and plenty of books, but these modernizations came with the sense that one was an outsider. They also came with the sense that an outsider could get to the inside with some effort.

At the University of Nebraska, Cather was ambitious in her studies and in her extracurricular literary activities, one of which was editing the Hesperian, the university literary journal. She studied with a journalism professor who was managing editor of the local town paper, and eventually he hired her to write reviews of itinerant theater productions put on by companies that passed through Red Cloud and Lincoln. (Her column was called The Passing Show.) Her reviews were often harsh, and because the acting companies were traveling from coast to coast, she became famous, or notorious, which led to a job with a magazine based in Pittsburgh called Home Monthly. When she left Nebraska for Pennsylvania, she was twenty-two.

Jim is ten, sent from Virginia, where both of his parents have died, to his grandparents in Black Hawk. Since he is the same age Cather was when she first experienced Nebraska, his immediate observations are telling—one is, “The only thing very noticeable about Nebraska was that it was still, all day long, Nebraska.” And his whole way of perceiving the world is changed by the emptiness of the landscape: “I had the feeling that the world was left behind, that we had got over the edge of it, and were outside man’s jurisdiction.” His grandparents are loving and kind, their cowboy hired man friendly and amusing, and almost as soon as he wanders out of the house and over to the distant garden, Jim realizes that he is “entirely happy” and has a revelation: “At any rate, that is happiness; to be dissolved into something complete and great.”

His sense of being right at home is contrasted to the difficulties of his nearest neighbors, the Shimerdas, whom he had seen on the train and who have just immigrated from Bohemia (now the western half of the Czech Republic, which was, in the 1880s, under the control of the Austro-Hungarian Empire). Even on the train, he had noticed Ántonia, who is twelve or thirteen, and he soon gets drawn into her life and the life of her family, which is difficult, partly because they have bought an undeveloped property sight unseen and partly because Mr. Shimerda never wanted to leave Bohemia in the first place. And so Ántonia must do something similar to Alexandra in O Pioneers!: make her own way but also do her best to save her family.

Cather gains a few things from ceding the narrative to a first-person male point of view—Jim is an active boy, raised without many restrictions, who can move at will in town and out in the countryside. He is not required to adhere to the same social norms as the girls are; the daughters of prosperous families have to behave like ladies, and the daughters of working families have to devote themselves to making money. He can also express all his varied feelings toward the girls he grows up with, who are much more the focus of the narrative than he is. Cather gives Jim Burden some of her own restlessness. He does well in school, goes to Lincoln, realizes that he is not cut out to be a scholar, and ends up in law school. But even as he succeeds, he cannot get his Black Hawk experiences out of his mind: “But whenever my consciousness was quickened, all those early friends were quickened within it, and in some strange way they accompanied me through all my new experiences. They were so much alive in me that I scarcely stopped to wonder whether they were alive anywhere else, or how.”

It is tempting for a reader to speculate about whether a novel, especially one written in the first person, is autobiographical, and certainly Cather’s uncanny ability to evoke the landscape (and the humanscape) of a town in Nebraska similar to Red Cloud invites that question, but the plot of a novel doesn’t have to be autobiographical to enable vivid perceptions and feelings; in fact, I would say when a plot is not autobiographical, the author feels a freedom of depiction that opens up the world of memory to bits and pieces that are alive but unattached to any particular history. In O Pioneers! and The Song of the Lark, Cather is interested in how Alexandra and Thea manage to achieve the successes they seek. My Ántonia is much more about who Ántonia is, what it feels like to others to recognize her charisma and to love her—yes, she undergoes many trials and is successful, and Jim admires her success, but what he is really interested in is how her beauty and toughness reflect the landscape she lives in and how he feels about that. My Ántonia is about permanence and ephemerality and how they coexist.

The first time Cather mentions My Ántonia is in a letter to her publisher from March 1917. She is living on Bank Street in New York City. She tells her publisher that she has set aside the book she had been working on and begun another, “a Western story which will run about the same length as O Pioneers!” She is halfway through the first draft and hopes to be finished in time for an autumn 1917 publication. In the summer, she goes back to Nebraska to receive an honorary doctorate and then back to Red Cloud, perhaps for inspiration. But she can’t get the manuscript completed because, like most Americans, or maybe most people in the world, she is preoccupied by the World War I. She writes that she thinks that the American entry into the war is the only thing that can save Europe and maybe Russia and maybe America itself—“If we don’t do this, we will have to be Prussians in the end.” The other letters she writes to her publisher about My Ántonia are focused on illustrations and binding, not on her progress or dissatisfaction or pleasure in the actual writing of the novel. When we read the novel, what is indeed amazing is how absent the war, or any sense of external danger to the world that she is writing about, is. It may be that in composing My Ántonia, Cather managed to successfully remove herself from the present and even more deeply immerse herself in her past.

Unfortunately, the war impinged itself on Cather’s life in June 1918, when her cousin G. P. Cather was killed in France and his death listed in one of the New York newspapers (the inspiration for One of Ours). She immediately wrote to her aunt, lamenting G. P.’s death but also recalling his restlessness and honoring his desire to serve a cause that she considered essential to the survival of modern society. Around the same time, she was sent the copyedited manuscript of My Ántonia. As with the illustrations, she is particular about the details of the style, the paper, and the layout. But she also writes to her brother, “It’s a queer sort of book. It’s at least not like either of the others.” This is maybe the best review an author can give her own work because it indicates that the book has surprised even her, challenged her own expectations and recollections, and taught her something new.

Cather sent the proofs back to the publisher in early August, and the book was published in October. The reviews were raves; in a letter to her brother Roscoe, Cather, always opinionated, says that she’s pleased that her brother and her parents “liked this book,” and she appreciates the excellent reviews, but she prefers The Song of the Lark because it contains “more warmth and struggle.” One reviewer, from The Nation, praised its “atmosphere of pure beauty.” Cather scoffs: “Nonsense, its [sic] the atmosphere of my grandmother’s kitchen, and nothing else.” A hundred years later, what I take from her remarks is that one of the things critics loved about My Ántonia was that it recalled a world of relative human innocence and natural beauty that readers knew, even as the book was being published, was disappearing because of technology, war, and urban expansion. My Ántonia is set, perhaps unknowingly, at a particular turning point in American history, where the plains and the mountains, people and towns, writers and readers, were simultaneously isolated and connected, able to feel the power of the landscape and also to escape it.

Jim Burden’s last visit to Ántonia is a visit to her victory—she has prospered on the farm she owns with her husband; she is mother to many active and good-natured children who have inherited her health and her wildness. She is happy. A hundred years later, we must set her happiness in the context of the history of the West—fifteen years after the publication of My Ántonia, drought and dust storms brought on by the mechanized plowing of the prairies would challenge the very idea that the land should have been populated, should have been cultivated, should have succumbed to the system of monoculture. Yes, Cather was right, My Ántonia is a queer book, flickering with darkness and light, a true representation of its time, both in terms of wisdom and in terms of ignorance.

We read novels for suspense and drama, and My Ántonia has plenty of both—the Shimerdas’ efforts, and those of the other immigrants whom Jim knows, are sometimes tragic, sometimes amusing, and sometimes rewarded. And there is always the pleasure of watching Cather’s characters develop—she is perceptive and detailed about their motivations, about their idiosyncrasies, and about how they affect each other. But finally, it all comes back to landscape, to humans changing and being changed by the difficulties and the beauties of the world they must contend with. It is also true, though, that we read older novels differently from new ones—we read them to understand what we have lost and what we have gained, what the author knew and what she didn’t know that she knew, but that we now understand shaped the world we are living in. Because of Willa Cather’s intensity of observation, My Ántonia remains a revelation.

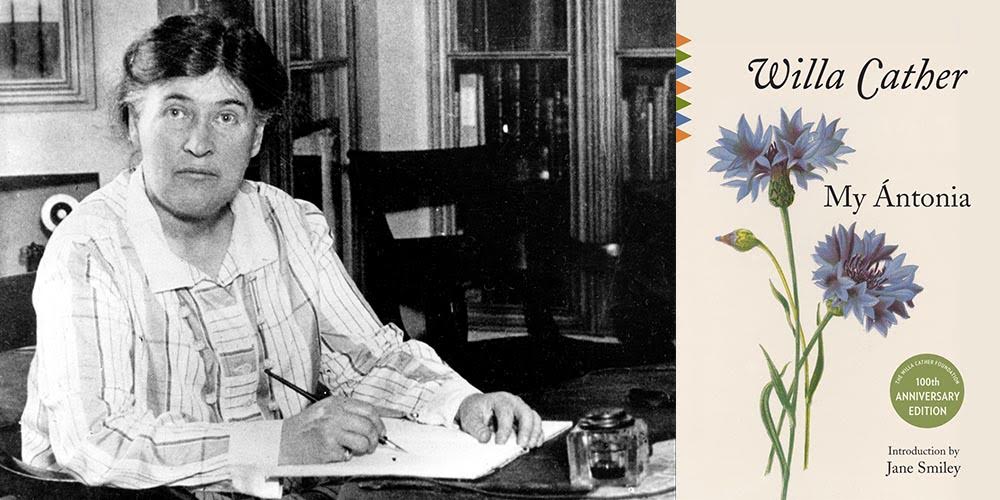

Jane Smiley is the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of numerous novels, five works of nonfiction, and a series of books for young adults. A member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, she has also received the PEN Center USA Lifetime Achievement Award for Literature. She lives in Northern California.

From the book My Ántonia, by Willa Cather. Introduction copyright © 2018 by Jane Smiley. Published by arrangement with Vintage Anchor Publishing, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

from The Paris Review http://ift.tt/2EVPZ4g

Comments

Post a Comment