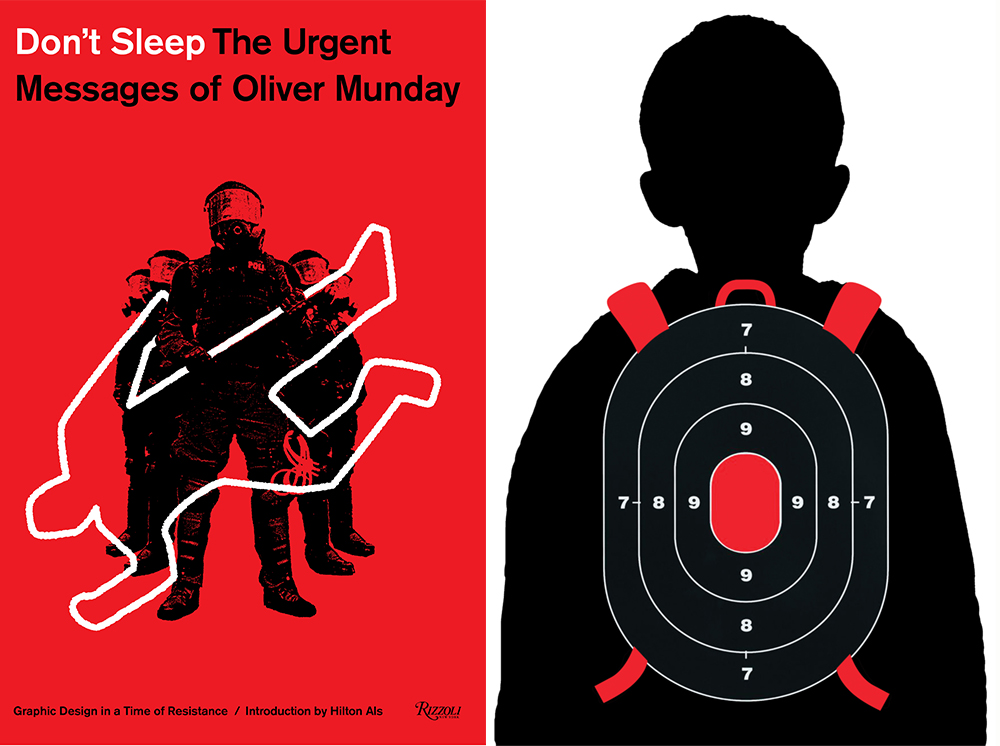

Perhaps the most striking images in Oliver Munday’s new monograph, Don’t Sleep (Rizzoli, March 2018), appear just before the title page. On the left-facing page is a nineteenth-century map of the Senate floor. On the page opposite is an illustrated cross section of the hull of a slave ship, scaled to the same size as the Senate and in the exact same semicircle shape. This encapsulates Munday’s design work: arresting juxtapositions, an engagement with the political, and above all, a deliberate, understated presence. As heavy as the visuals are, Munday’s hand is light. The images speak for themselves.

Don’t Sleep is a powerful survey of thirty-three-year-old Munday’s career thus far. The title, which asks readers to stay alert to the implicit and explicit messages of an image-saturated culture, also calls to mind “wokeness.” Though Munday is hesitant to call himself an activist, he readily acknowledges the role of design in various social movements, from May 1968 to Cold War Cuba. Munday’s editorial illustrations, posters, and book jackets draw attention to social-justice issues—and awareness is the first step in making change. He is after, as he says, “the thing that makes you stop and think for just one extra moment.”

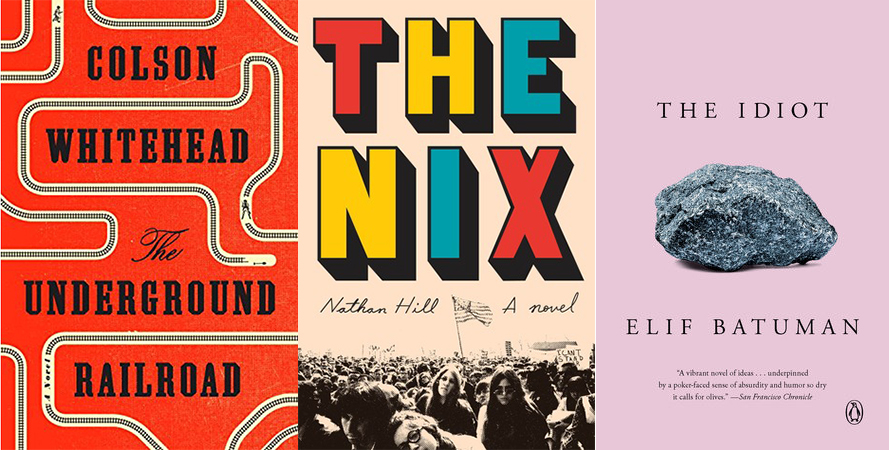

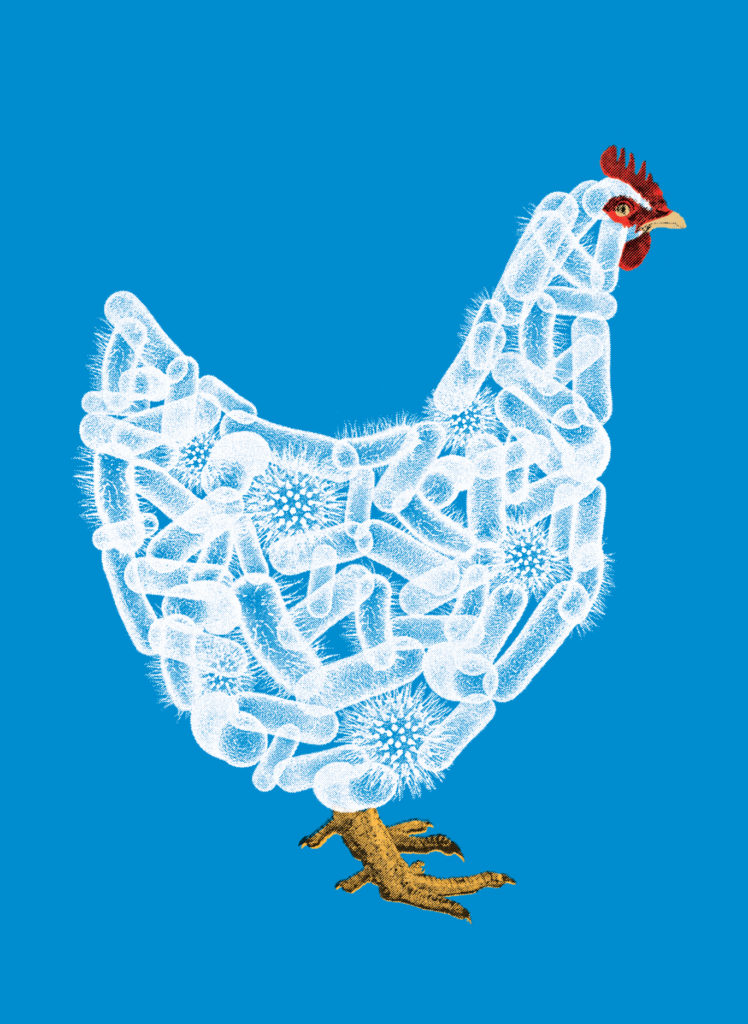

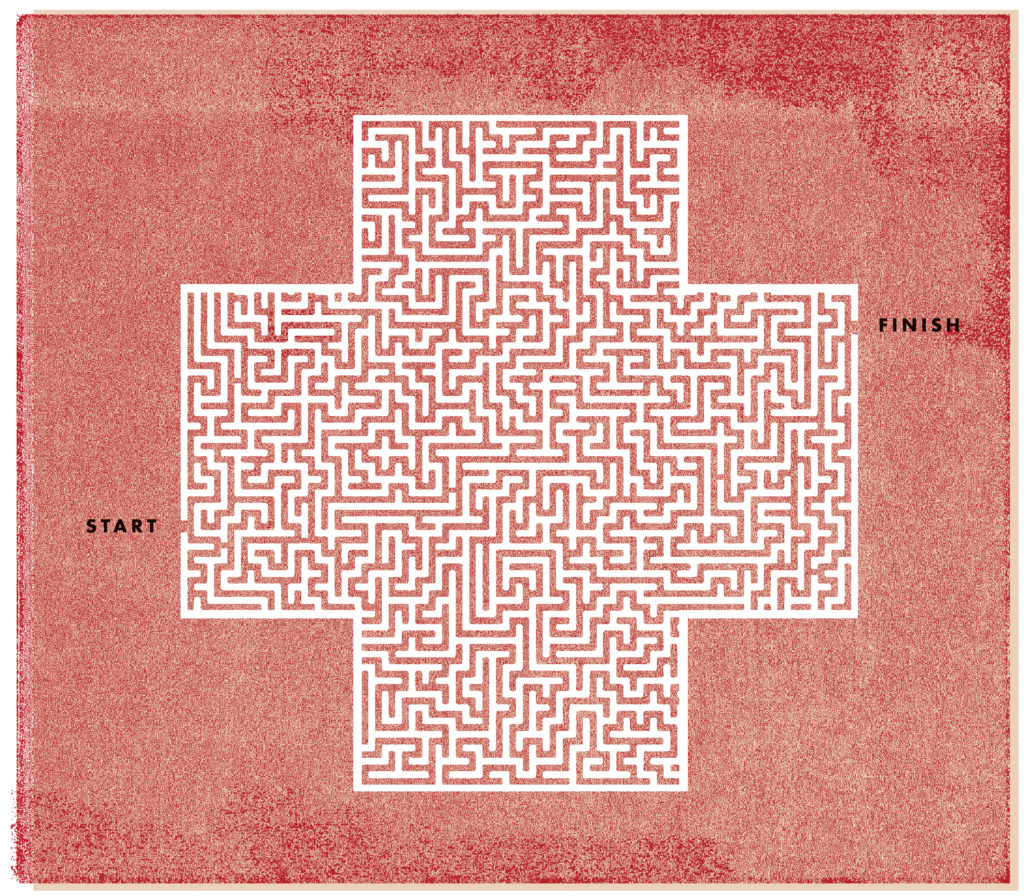

Munday is responsible for the covers of Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad and Margo Jefferson’s Negroland, as well as Elif Batuman’s The Idiot and Nathan Hill’s The Nix. He is a fixture in the pages of The New Yorker, the New York Times, and The Atlantic, and he has designed numerous iconic covers for Time magazine. The table of contents in Don’t Sleep reads like an accounting of the thorniest problems facing America today: Criminal Justice, Race, Democracy, Education, Environment, Heritage, History, Economy, Health, Foreign Policy, War. Working in a variety of styles that draw on his constructivist influences but also street art, Pop art, and collage, Munday’s illustrations tackle everything from the Israel-Palestine conflict to the Flint water crisis. Also on display is his work for nonprofits like Cuba Skate, the Baltimore Urban Debate League, and Dave Eggers’s 826 D.C.

The standout section, “Heritage,” is a visual essay. In these pages we are confronted by a stock photo of the White House, blocked from view by a blank check; a statue of a Civil War soldier posing proudly with an automatic weapon; and the Washington Monument repurposed as a giant pillory. In other images, Munday, like Kehinde Wiley, imagines black bodies into classical Western art and architecture. One image replaces the bust of Alexander von Humboldt in Central Park with one of Kalief Browder, the teenager who spent three years on Rikers Island after being wrongly accused for stealing a backpack. (Browder committed suicide two years after his release.) “Kalief Browder is a hero,” Munday says. “He was an explorer, just like Humboldt, only he was forced to explore the darkest recesses of our broken criminal justice system. I wanted to imagine a world where we honor those who suffered wrongly.”

Munday grew up in Washington, D.C. His mother worked as a fundraiser for different causes and his father was in real estate. After they divorced, his mother married a personal injury lawyer, and the family suddenly “jumped up a rung on the class ladder.” Though some accused Munday’s stepfather of being an “ambulance chaser,” he was actively involved in the community, winning a high-profile case for the families forced to evacuate their homes by a fuel spill at a BP Amoco gas station in Southeast Washington. Munday remembers the reporters and cameramen that occasionally showed up at the law firm, and the seeming intrigue of civic engagement.

After a brief and unsuccessful stint at St. John’s, a Catholic JROTC school, Munday transferred to Woodrow Wilson High. Wilson had a reputation. Though located in the affluent, predominantly white neighborhood of Tenleytown, due to school closings and rezoning it also served all of Southwest Washington north of the Anacostia River, which was predominantly black. Munday’s mother worried about him falling into “the wrong crowd.” In the 1980s, the school was notoriously violent. The social issues plaguing D.C. played out in the hallways. Teachers were beat up. A principal was thrown out of a window. Key figures in the 1980’s D.C. hardcore scene had gone to Wilson, including Ian MacKaye of Minor Threat and Fugazi, whose recollections of his time there involved a classroom catching fire and a kid bringing a shotgun to school. “Socially,” Munday writes in the preface to Don’t Sleep, “I was often the only white boy—a novelty—and I enjoyed being considered down. As I got older, the distinction proved complicated. An internal tension took hold…Our home and its abundance of unused rooms were hard to explain.”

Munday was more interested in basketball, sneakers, and seeing go-go bands like UCB than he was in his studies. The only class he liked was Intro to Computer Graphics. Both of Munday’s paternal grandparents were artists, but he attributes his career to the “thrilling revelation” that “design was everywhere, omnipresent to the point of invisibility.” His work directs the eye toward the margins. He took the class four times before graduating high school.

He studied design at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore. The state of the city threw the relative privilege of MICA into sharp relief. Munday studied under Bernard Canniffe, a proponent of Blue Collar Design Theory, which encourages designers to partner with local institutions—in Munday’s case, the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health—to take direct action in improving the social conditions of their city. Munday took Canniffe’s class three times, and was exposed to Russian constructivism and the work of Emory Douglas.

When I asked Munday if he would call himself a propagandist, he paused longer than most designers might, before acknowledging that he often works for magazines, newspapers, and publishers, meaning he’s usually charged with “selling something.” But he’s careful about what he chooses to sell. “Moral calculation comes into it,” he said. “I’ve turned down a good number of projects because on some level they were working against something I believed in, politically, economically, or socially.” He told me about buying his first house in the Butcher’s Hill neighborhood of Baltimore just before the market crashed. “Homes were inexpensive, and I got a loan from Wells Fargo with zero money down. And then I ended up underwater.” Years later, when Wells Fargo approached him with a project, Munday turned it down. “It was one of those moments when you think, absolutely not,” he said. Munday often steers away from potentially lucrative work in branding and advertising in favor of book covers (he worked at Knopf for four years) and editorial illustrations with a political bent.

Halfway through my conversation with Munday, we realized that neither of us had a solid working definition of the phrase “graphic design.” The first Google hit read: “the art or skill of combining text and pictures in advertisements, magazines, or books.” Munday took issue with the definition. “It’s not just that. Protest signs are design,” he says.

“The first task of the graphic designer is communication, which often involves language,” he added. But his own work eschews text whenever possible. When he worked at Knopf, he repeatedly tried to push through book covers with no words on them. He doesn’t have anything against typography; Munday uses images the way writers use words. In his introduction to Don’t Sleep, Hilton Als comments that Munday, in his book jackets and editorial illustrations, “collaborates with the text by finding an element in the writing that invites it…The excitement his work generates is as old and new as the ancients reacting to the news of the world through alchemy, the beauty that comes when images become words, and words, images.”

It’s rare that a monograph can be accurately described “important” or “necessary.” Don’t Sleep, however, fits the bill. Isolated from their original context and arranged by theme, Munday’s images accumulate power—the power not just to move readers, but to move them to action. Don’t Sleep is the kind of book that burns through the coffee table it’s left on.

Andrew Ridker’s first novel, The Altruists, is forthcoming from Viking/Penguin in 2019. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Paris Review, Guernica, Boston Review, The Believer, St. Louis Magazine, and elsewhere.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2GdXXm0

Comments

Post a Comment