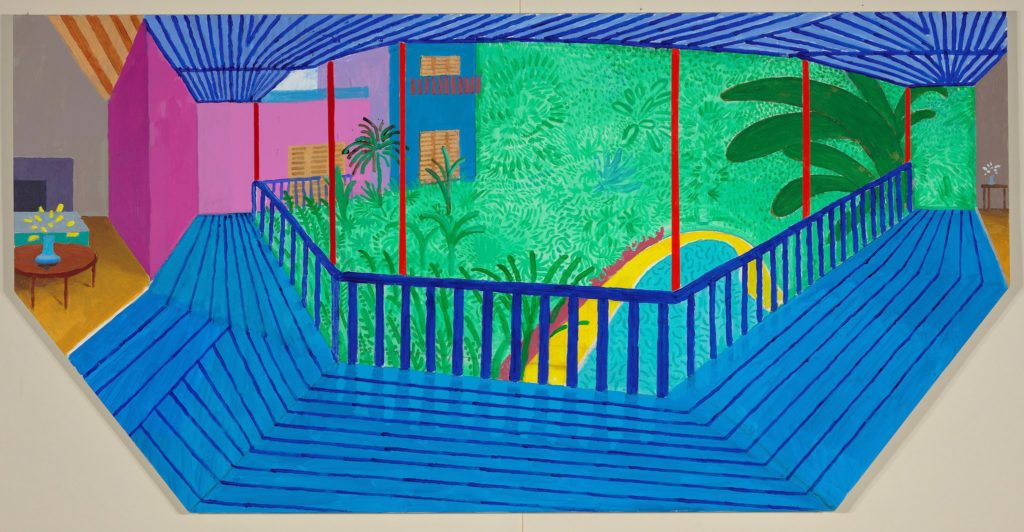

David Hockney’s show of new work, currently up at Pace in New York, is an explosively energeting exploration of “reverse perspective.” Hockney deploys hexagonal canvases, the lower ends notched out, so as to allow the eye to bend the picture far beyond the frame. As Hockney quips, “far from cutting corners, I was adding them.” In Lawrence Weschler’s catalogue essay, Hockney suggests what he means by “reverse perspective” by way of an allusion to an experience he once had coursing through the arrow-straight 18-kilometer St Gotthard pass road tunnel, the tiny pinpoint of light ahead epitomizing “the hell of one-point perspective.” “I suddenly realized,” Hockney tells Weschler, “how that is the basis of all conventional photographic perspective, that endless regress to an infinitely distant point in the middle of the image, how everything is hurtling away from you and you yourself are not even in the picture at all. But then, as we got to the end of the tunnel everything suddenly reversed with the world opening out in every direction. (…) And I realized how that, and not its opposite, was the effect I wanted to capture.”

In one of Hockney’s first experiments in his recent series, he took the Fra Angelico San Marco Annunciation (a masterpiece of one-point perspective)— a poster of which used to grace the upper corridor of his elementary school — and turned it inside out, offering a sense of what it might have looked like in reverse perspective.

Weschler’s catalog essay, two long adapted excerpts from which we will be publishing this week and next, goes into further detail on the taproots and implications of Hockney’s current reverse-perspective passion. The first, below, involves an improbable recent mentor. —Nadja Spiegelman

During this period, Hockney came under the spell of a new intellectual mentor. He’d always been a ferocious autodidact, and in the past, entire bodies of work had come into being in tandem with his discoveries of one fresh contemporary influence or another: the physicist David Bohm and his implicate order, the historian George Rowley and his ideas on moving focus in Chinese art, the art and science historian Martin Kemp and the optical physicist Charles Falco and their notions on mirrors and lenses as possible contributors to the rise of one point perspective (and the optical look it began enforcing) as far back the start of the Renaissance. Approaching eighty years of age, Hockney was as susceptible to such sudden passions as ever, only the inspiration this time round proved perhaps his most surprising yet, a Russian Orthodox monk and his writings from almost a full century earlier.

Early on in the creation of these new notched paintings, David had been rhapsodizing on the virtues of reverse perspective, and one evening, one of his friends and assistants, Jean Pierre Goncalves de Lima (universally referred to around the studio as JP) decided to burrow into the world wide web in search of further clarification on what this boss of his kept yammering on about, where he quickly came upon a long essay, from 1920, offered forth in its entirety, indeed entitled “Reverse Perspective” and credited to one Father Pavel Florensky of Moscow, Russia. JP printed out a copy of the eighty-page monograph and left it on David’s studio chair for David to discover in the morning, which indeed he did, becoming progressively more engrossed (“positively thrilled,” being the way he described his reaction later that very day when he called me up, along with many other friends no doubt, positively ordering us all to download the text and get back to him with our reactions).

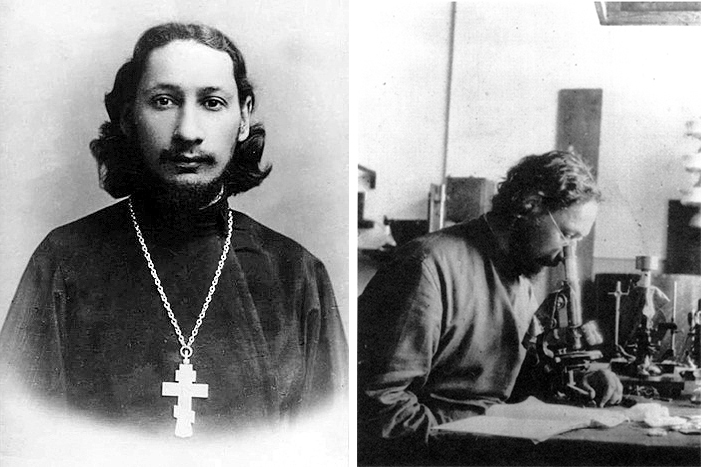

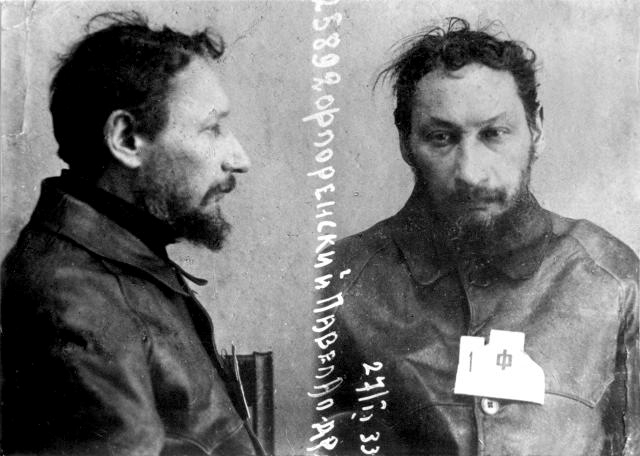

And the text was indeed something—as was its author. Florensky, born in 1882 in Azerbaijan, the scion of secular Westernizing parents (his father a Russian railway engineer, his mother the cultured product of ancient Armenian nobility), proved a mathematical prodigy from his earliest years and went on to do path-breaking work in non-Euclidean mathematics while also pouring himself into wider scientific studies more generally, but apparently following a visit to Tolstoy in 1899 fell into a growing spiritual crisis in which he came to doubt the primacy of the scientific positivism that had guided his studies thus far. Following graduation from Moscow State University in 1904, he declined the offer of a teaching position in mathematics, instead repairing to the nearby holy city of Sergiev Possad (site of the Trinity Lavra of St Sergius, the most important monastery in the Russian Orthodox Church) where his theological studies culminated in his being ordained as a priest in 1911 (though he married and would have five children). Although he wrote widely on philosophy and theology (his essays on the idea of the Divine Sophia would later become central to the concerns of feminist theologians), he nevertheless continued his equally far-flung scientific investigations, all the while trying to meld the two vocations. Following the Bolshevik Revolution, and even though the Communists shut down many of his most beloved Orthodox institutions, he threw himself into technical work, particularly on behalf of the electrification of rural soviets, under the sponsorship of Trotsky himself (notwithstanding his insistence on wearing clerical robes all the while). By 1932, however, Trotsky was gone and Stalin, finding the charismatic and querulous cleric an increasing nuisance, had him exiled to Siberia, where he launched into investigations on the nature and properties of permafrost, further path-breaking research that has become increasingly relevant in recent years with the rise of global warming. Meanwhile, in 1937, at the height of his Red Terror, Stalin had Florensky brought back to St Petersburg and following a brief trial, summarily executed—that being the very year, as it happens, of the birth of David Hockney in Bradford, England.

The point is that on top of all of that, Florensky was also a hugely influential art critic and aesthetic theorist, one of the leading lights of Russia’s Silver Age and well known to the likes of Malevich and Kandinsky (and such writers as Alexei Biely and Sergei Bulgakov). His Reverse Perspective essay, in particular, dates from a moment in 1920 when Bolsheviks were busily imputing the value of the medieval Orthodox icons they were tearing off the walls of museums and monasteries, dismissing them as hopelessly “primitive” for their allegedly clumsy handling of modeling and perspective (the way, for instance, a nose might be seen to be going one direction, while the lips went another and the eyes a third—not in any way, at any rate, as in “real life”). But Florensky fired back, marshalling tremendous erudition to argue that if, as far back as Babylonian and Egyptian times, artists and craftsmen continually made similar “errors,” it was not because they didn’t know about rigorous one-point perspective (they would have had to call on such knowledge to be able to build pyramids and the like) but because they sensed there was something wrong with its practice when it acutally came to the depiction of “real life” in all its timely and timeless vivacity–and they chose not to use it. In Ancient Greece and Rome, Florensky showed how conventionally one-point perspectival tricks first began being deployed on theater sets with the express intent of deceiving audiences, such illusionistic effects being likewise prized on the walls of decadent villas, say, in Pompeii, even though they really only registered as accurate from one specific location, completely falling apart from any other point of viewing. Over and over again, Florensky marshalled arguments that Hockney himself would start deploying over sixty years later as he launched into his photocollages around 1982 (one hundred years almost to the day after the good monk’s birth, though Hockney obviously hadn’t known this at the time). For example, Florensky pointed out how young children, when asked to draw their house, say, will naturally include the front, the back, the tree and the doghouse in the backyard, and so forth (all of that correctly, since all of those details form part of the house they live in), and they have to be rigorously trained instead to draw in a “correct” manner, which is to say as if arbitrarily standing stock-still with only one eye open, and then only to accept that way as accurate. For that matter, Florensky, like Hockney after him, pointed out that we ourselves never ever see in rigorously abstracted perspective (the way a camera does) because, for starters, we look out at the world from two eyes simultaneously, and for that matter our eyes and bodies are always in motion, as we construct our actual sense of the world across time from all those multiple vantages.

You can see what thrilled Hockney. At one point, for example, Florensky writes how “it was not in pure art that perspective arose, it came out of applied art sphere” (theater design in antiquity, and subsequently alongside the rise of positivist science on the far side of the Medieval era) “which enlisted painting in its service and subordinated it to its own purposes.

[However,] the task of painting is not to duplicate reality, but to give the most profound penetration…of its meaning. And the penetration of this meaning, of this stuff of reality, its architectonics, is offered to the artist’s contemplative eye in living contact with reality, by growing accustomed to and empathizing with reality, whereas theater decoration [for example] wants as much as possible to replace reality with its outward appearance.

(One of the problems with conventional photography, Hockney often says, is the way it can only capture surfaces.)

For that matter, you could see what thrilled me, for in the sentences that followed, Florensky insisted that “stage design is a deception, albeit a seductive one, while pure painting is, or at least wants to be true to life” (his italics, though as it happens, those last three words track exactly with the title I gave my own 2008 collection of twenty five years of conversations with Hockney, starting with those photocollages in 1982)—“not a substitute for life,” Florensky went on, “but the symbolic signifier of its deepest reality.”

It’s of course interesting how Florensky locates the original sin of perspective in antique theatrical design whereas contemporary opera staging proved one of the places where Hockney himself chose to elaborate his critique of one-point perspective, but that was only because Hockney was consciously trying to wrestle radically free from what Florensky saw as the very foundations of a prior perspective-infused tradition.

Florensky meanwhile has a slightly different take from David’s on the waning of the reverse (or multiple, or moving) perspective traditions that had, as far as he was concerned, haloed the art of the Middle Ages (both in the West and in Mother Russia. Although Floresnksy saw the growing Renaissance focus on humans in their secular individuality as opposed to their sacred community as one of the well-springs renewing the antique theatrical bias toward a one-point perspective that by definition required a solitary individual’s solitary gaze (out of one eye), and of the positivist science such a revolution in turn helped occasion, he declined to point to a particular moment when the world views suddenly flipped (as Hockney was to do with the Great Wall that formed the heart of his research program leading up to the Secret Knowledge volume of 2000, in which he argued that something revolutionary must have occurred between 1425 and 1435, a point at which artists from Bruges to Florence, from Van Eyck to Brunelleschi, must have suddenly started using optical aids and it was “as if from one decade to the next, European art put on its glasses.”) Florensky argued for a more gradual transition, pointing out that as late as Leonardo (The Last Supper, 1495-7) and Raphael (The School of Athens, 1509-1), masters were deploying multiple perspectives to heighten spiritual interpretations of their material.

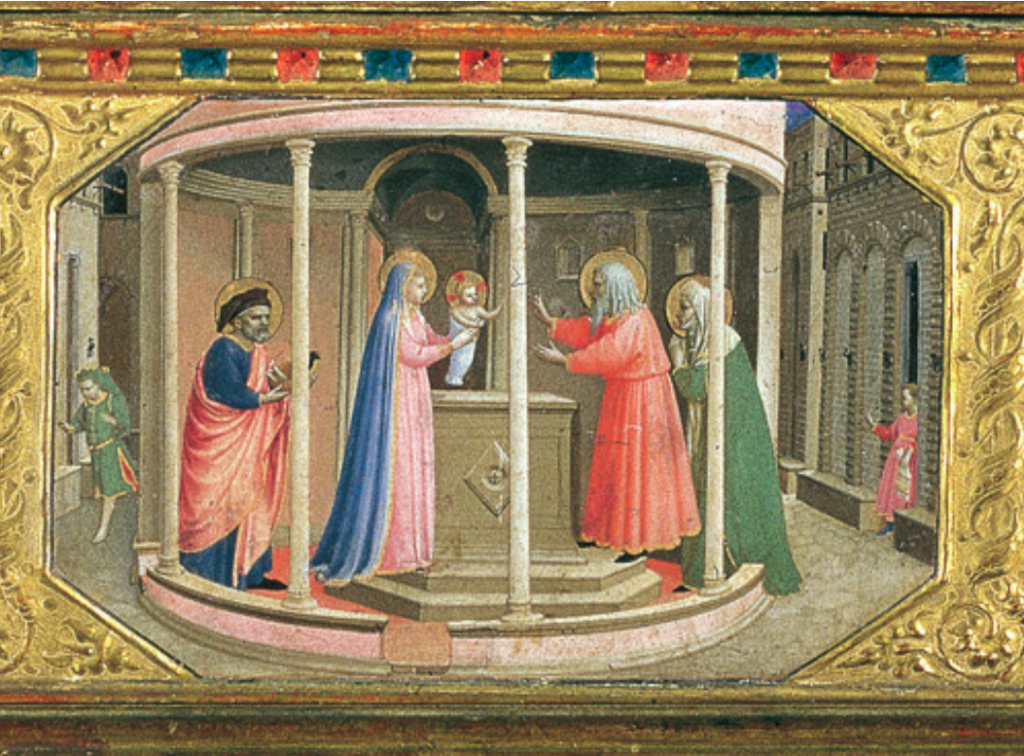

Notwithstanding the reading of which, I was thoroughly startled a few weeks later in Madrid, when visiting the Prado, I came upon another Fra Angelico Annunciation (c. 1430), similarly squeezed into a tapering one-point perspective:

Underneath it, there was a predella consisting of five scenes all of them (but especially the second and the fourth) laid out in pure Hockneyesque notched reverse perspective:

So, go figure.

“Something New in Painting (and Photography) [and even Printing]” will be on view at the Pace Gallery from April 02 to May 12th.

Lawrence Weschler, late of the New Yorker and director emeritus of the New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU, is the author of over twenty books on myriad subjects. He is currently completing work on a biographical memoir of the years, during the early eighties, when he was serving as a beanpole Sancho to Oliver Sacks’s capacious Quixote, due out in 2019.

Excerpted with permission from David Hockney: Something New in Painting (and Photography) [and even Printing]; introduction by Lawrence Weschler, Pace Gallery, 2018.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2qDcTUM

Comments

Post a Comment