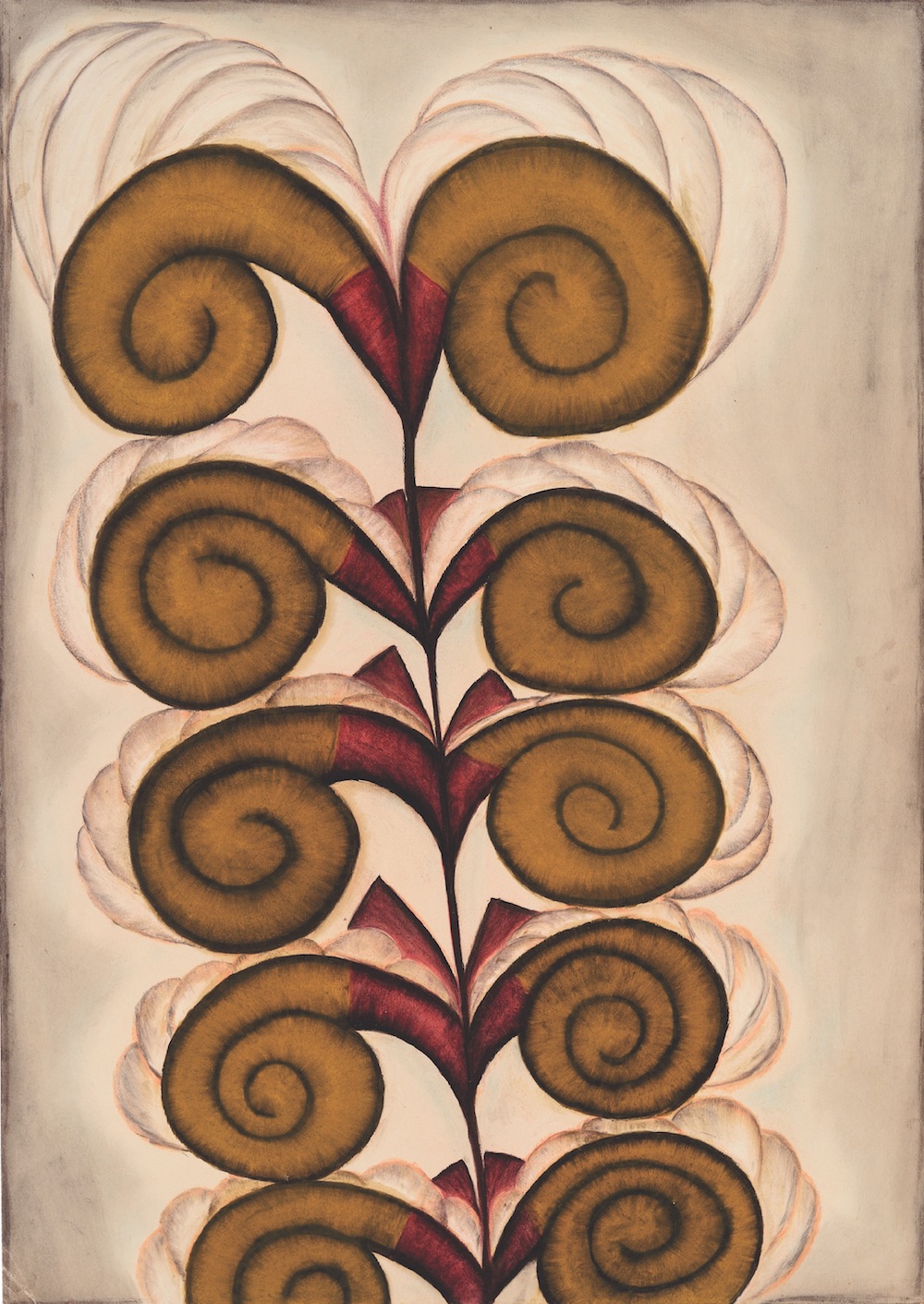

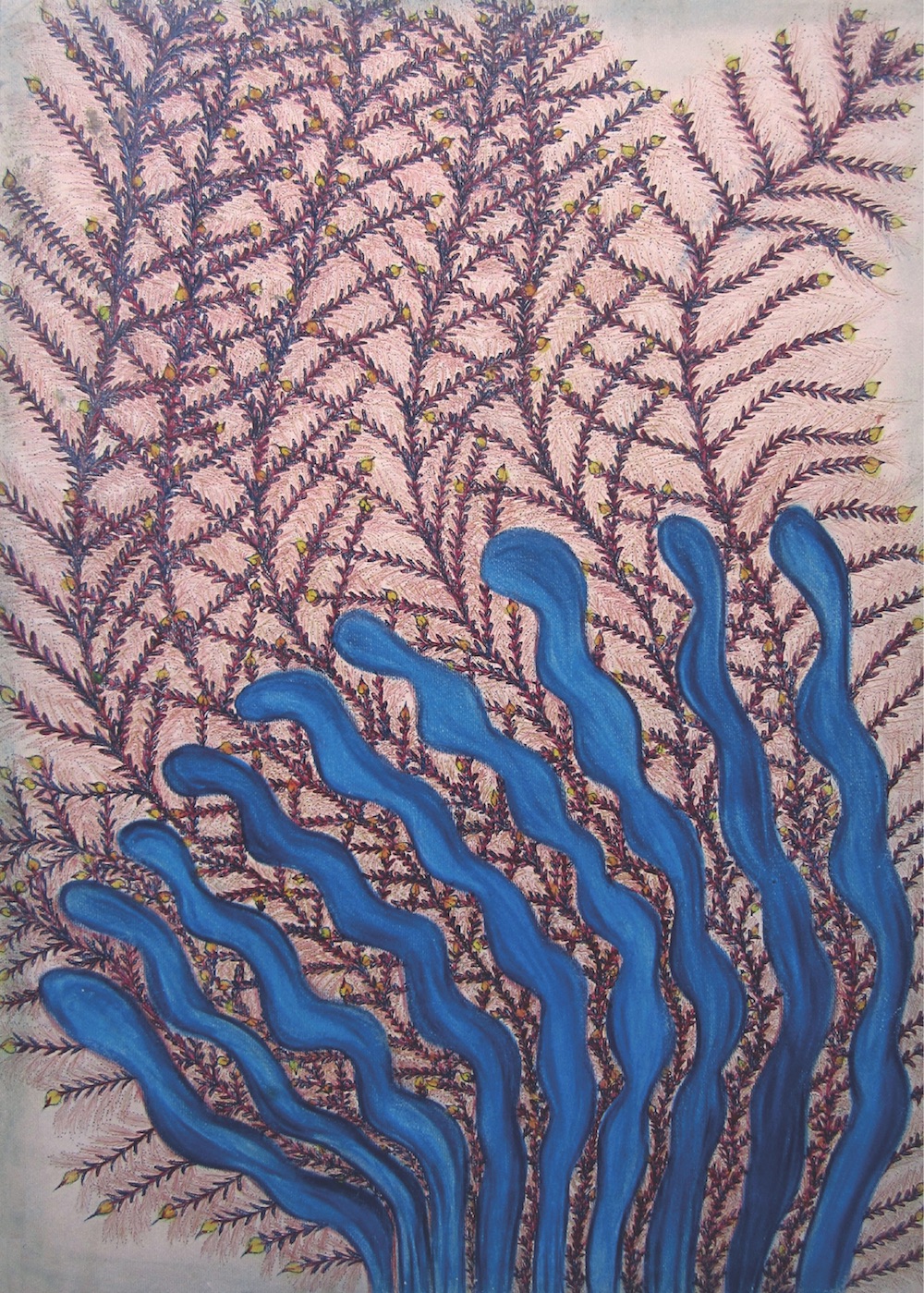

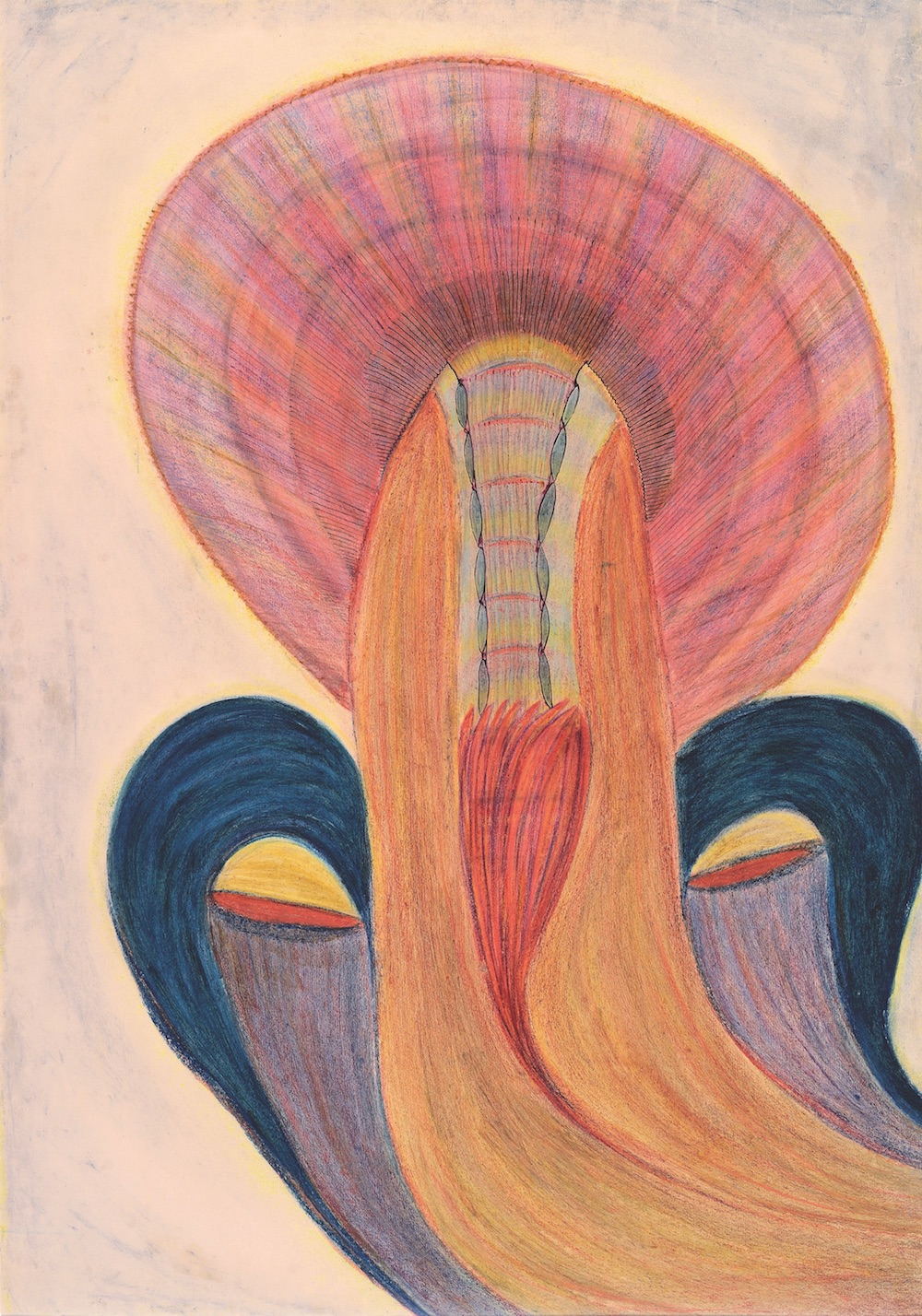

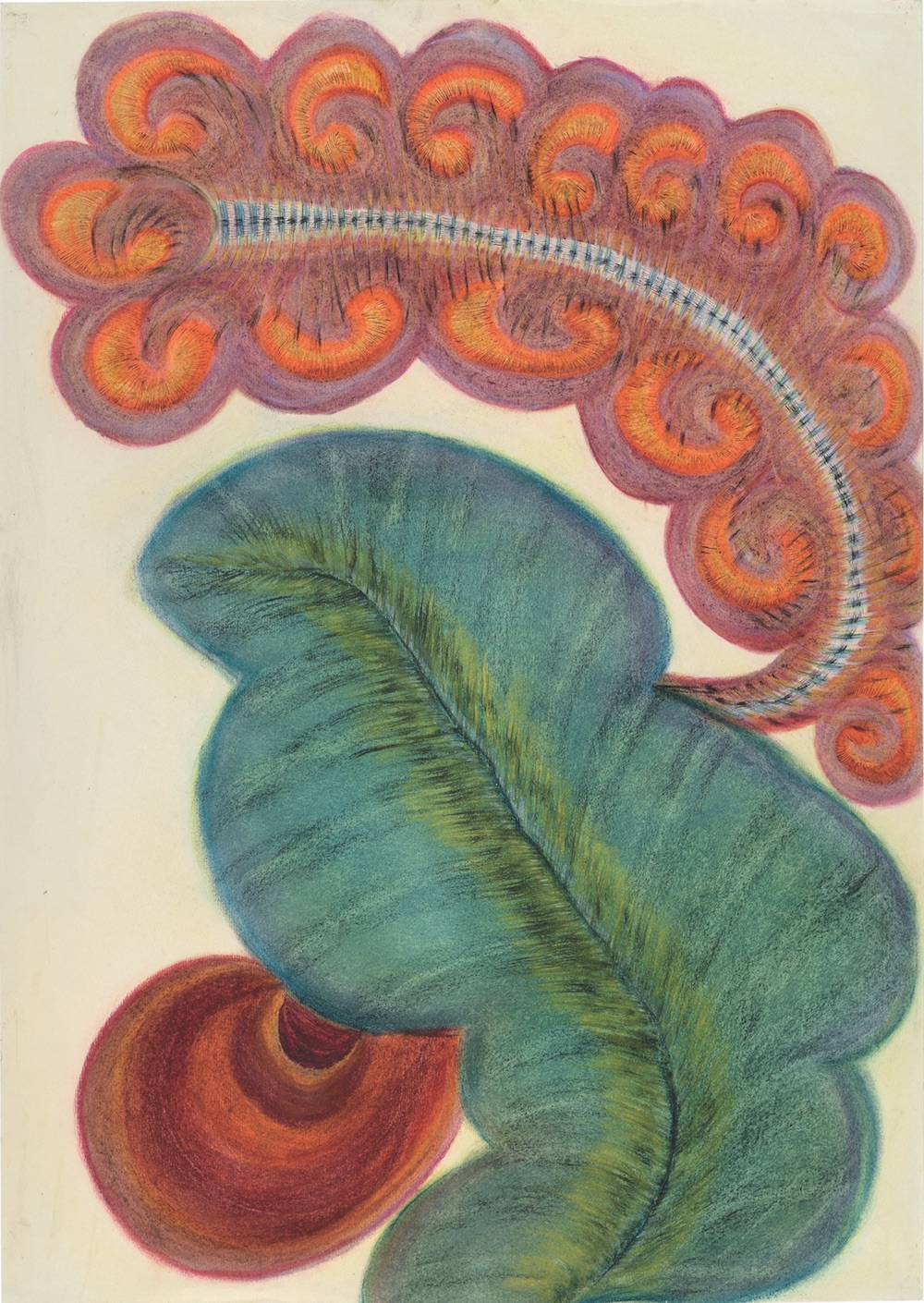

Like most artists, Anna Zemánkova was encouraged, from a very young age, to pursue a more lucrative career. From the age of fifteen to eighteen she studied dentistry, and then worked as a dental technician until her marriage, when she forwent paid labor in order to care for her children. In 1948 she and her family moved to Prague, and when she found herself increasingly depressed, her son, a sculptor, implored her to pursue the creative work she had previously disavowed. Early in the morning, before anyone else arose, she’d sketch pastel and ink onto large swaths of paper, creating botanical dreamscapes all her own. As a self-taught artist, Zemánková tends to be described as Art Brut, but her Art Brut is of a mysterious and magical strain. She believed her inspiration was derived from a divine source: “I am growing flowers,” she said, “that are not grown anywhere else.” Following a major retrospective of her work at The Collection de l’Art Brut in Switzerland last summer, Kant books has released a stunning 300 page monograph.

Excerpted from Anna Zemánkova, edited by Anežka Šimková and Terezie Zemánková, and released in March 2018. Published by arrangement with Kant Books.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2vYsNOJ

Comments

Post a Comment