Hair is a large part of the wonderment—and objection—Beyoncé courts each time she holds a mic. As the critic madison moore writes of her “haircrobatics” in 2014, hairography is “the special genius of Beyoncé’s stagecraft” and “punctuates everything else happening on stage: the lights, the dance moves, the glitter, the sequins, the music.” Hair for black cultures at large is often a vehicle for small acts of daring, for everyday articulations. But the newest iteration of the natural-hair movement does not welcome all black hair equally. The natural-hair revolution, a public-facing campaign corroborated by name-brand moisture treatments, the YouTube “hair journey,” and op-eds in the New York Times, embraces the kinky, the nappy, and all manners of patterns and styles still dubbed “unruly” by the nonblack population—or so natural-hair enthusiasts claim. But the natural-hair movement puts forth a false consensus of what black representation should look like that accommodates the standards of nonblack bystanders.

Andre Walker’s trademarked typing system, the taxonomy of four hair types upon which the natural-hair movement relies, has failed to yield textural egalitarianism—as my fellow lowly type-4 girls can attest. There is a tendency to map our hair on a spectrum from weave to Afro as a stand-in for anti- to pro-black politics. If she, he, or they wear their hair straight, they are lost, some say. If it is long, this person is lost—unless of course it is natural and long, in which case it is revered above the teeny-weeny Afro. No matter if Miss Thing takes their black behind to a black-ass beauty shop in a black-ass neighborhood to hand over their black-ass bottom dollar to a black hairdresser who, like a chemist, wields oil, water, paste, and heat to transformative results—if they walk out with something pressed, bumped, sewn, or curled, they are lost.

The inventions borne of our spaces—the wigs, weave, and crochet—encompass entire aesthetic worlds. The people who use and wear them are not, for the record, lost. Nor missing, if what one can see in the shops or on the bus or on Instagram are any indication. These techniques—a hairline too seamless for even God to tell, locs in every dreamy color, a relaxed pixie cut worthy of Sophisticate’s—go unsung by the natural-hair movement. The movement means well, but it adheres to a sense of naturalism that leaves out the ingenious wonderland of black hair over the past century. Perfected if not pioneered by queer black and brown folks who inhabit a diversity of identities and experiences, these technologies bring to life the everyday avant-gardism that has long been a part of black cultures. As I’ve written before, “Looking fly is a labor not necessarily made legible to activism.”

As an artist who embodies so many intersecting traditions of Afro-techne—including, of course, her own distinct Southern black American roots—Beyoncé embraces the gamut of black hair practices. If she may be allowed a preference, we could point to some consistency on color—a sure sign, detractors say, that she worships whiteness. Bey garnered new fans when she swung her blonde braids out the window of a moving El Camino in the video for “Formation,” but despite those who claim that Beyoncé “grew into” her blackness, Bey’s aesthetic has been black the whole time, in life and performance.

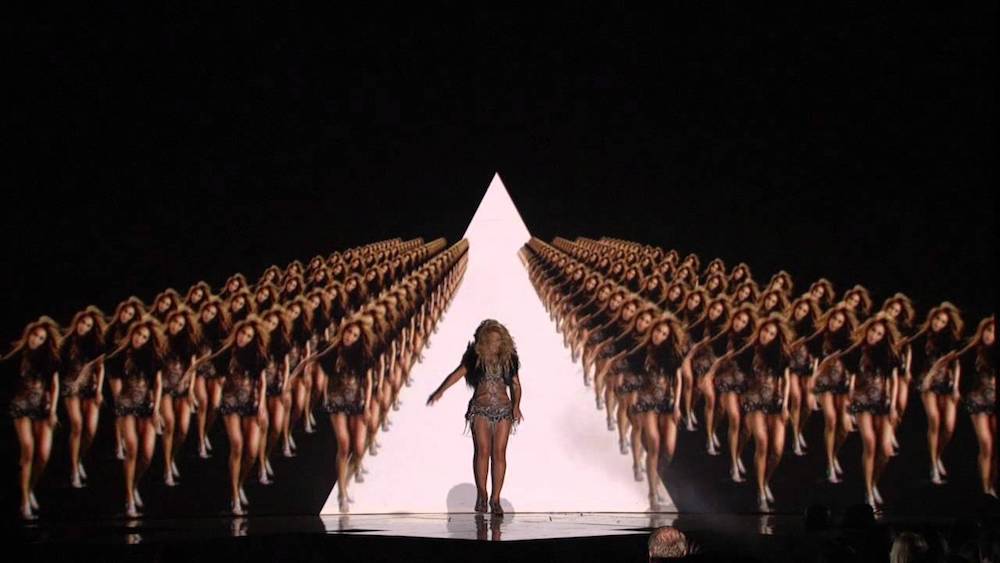

Just as iconic as the click bops that signal the start of Beyoncé’s “Run the World (Girls)” is her synchronic shaking of the shoulders, up-down-down, up-down-down, while her face turns right to left to right to left. “Girls, we run this mutha.” In the track’s 2011 music video, a patchwork Brian Lichtenberg vest accentuates the vertical motion, crosscut by Beyoncé’s beachy mass of long blonde hair moving side to side. This dynamism carries into live performances. For example, during the Billboard Music Awards and the season finale of The Oprah Winfrey Show later that year, Bey’s fringe and big hair amplified her fast weight-shifting movements. For the Perth, Australia, stop of her The Mrs. Carter Show World Tour in 2014, Beyoncé appeared in a short wavy bob that flipped on beat with the delicate epaulettes of a white textured bodysuit. The choreography is a motif whose patterns were intended for us. Us, the “beautiful, “loyal” “ride-or-dies” whom she shouted out at the end of her historic Coachella performance on April 14 this year. As she stood atop a twenty-four-step bleacher, shrugging and tossing once again, her voluminous blonde cascade played peekaboo with the face we know so well.

During the summer of 2006, an online petition emerged addressed to Columbia Records requesting that “Ms. Beyonce’ Knowles, Columbia Records, Music World Entertainment, and all other entities associated with the creative process of creating the long-form music video known as ‘Deja Vu’ reshoot aforementioned video immediately.” The petition claimed to be the work of fans who considered the production “an underwhelming representation of the talent and quality of previous video projects of Ms. Knowles.” The fast-paced movement—of the camera, of Bey—“causes one to get dizzy and disoriented,” the petition said. The choreography, it continued, was “erratic, confusing and alarming at times.” A scene between Bey and Jay-Z in which the former dances all up on the latter, whipping a sleek ponytail around, is described as “alarming.” The petition accumulated more than five thousand signatures, but the video was not reshot. This would not be the last time Bey would be urged to take up less space.

Beyoncé performed “Déjà Vu” at Coachella, accompanied by a band as big and boisterous and loud as the waist-length waves falling from her head. In both performances, her husband joined her, and they looked just as joyful now, on the other side of a decade-long marriage and the birth of three kids, as they did in 2006. Up against her man, Beyoncé arched her back and mouthed the letters H-O-U-S-T-O-N while her hair reached for the ground behind her.

I watched the performance through grainy fan-made footage as Beyoncé’s sister, Solange, jogged out onstage during “Get Me Bodied” to join Bey in a reenactment of the track’s music video. The lyrics command listeners to “pat your weave, ladies, pat, pat your weave, ladies,” among other black celebratory stunts: “drop down low and sweep the floor wit it,” “do an old-school dance,” “wind it back, girl.” In the video, Bey sits sandwiched between Solange, Kelly Rowland, and Michelle Williams, patting her slick and snatched ponytail with two hands. Onstage, the two very different sisters, in two different shades of blonde, synced up, laughing, to pat their respective ‘dos.

With diasporic intertexts in sound and footwork, hair movement—hairography—deserves due appreciation. Especially Beyoncé’s—she is so attuned to wind fans that mid performance, she bent down and righted an errant wind fan herself. When I watched Bey walk up and readjust the wind flow to receive the current she deserved, I thought of the beautiful Octavia St. Laurent in Paris Is Burning, climbing atop some chairs in heels and a pencil skirt to catch the breeze of a steel pedestal fan. Within the beats and steps that draw from Houston, New Orleans, New York, Nigeria, Atlanta, Jamaica, and Mozambique—the step show, the jazz club, and the dancehall—there is also the ballroom, felt through each theatrical bob and wave of Bey’s head. What else could be summoned to compel a braid to wind around her body and land on her shoulder just so?

At Coachella, Bey’s hair whipped and bounced and exceeded the limits of her body while also remaining under its command. A compilation of her finest moments of hairography would better rehearse the entire show, though I do have favorites: the double nod to punctuate “I slay”; the coquettish curl behind the ear as she surveys the row of bugaboo pledges; a triumphant head shake to capstone her step show; the in-sync lift and sway beside Kelly and Michelle, each with an expressive style all her own. Although I was privy to only her first Coachella performance, I imagine the tall strawberry ponytail she wore the second weekend was treated to similar choreography.

When she was interviewed by Diane Sawyer in 2006, Beyoncé said, “I wanted to be more like Josephine Baker because she didn’t—she seemed like she was just possessed, and it seemed like she just danced from her heart, and everything was so free.” On a dim festival stage the past two weekends, Beyoncé reanimated Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2012 TED Talk, “We Should All Be Feminists,” and its citation in 2013’s “***Flawless.” Out of a twenty-nine-minute speech, the sample begins here: “We teach girls to shrink themselves, to make themselves smaller.” The choice of the line was no accident.

“This is everything and more that I dreamt of it being,” Beyoncé told an audience she largely couldn’t see. She began the final song, “Love On Top,” in a cappella, relatively serene yet ever a diva, down to the smallest of microadjustments. She returned home, center stage, to conclude the set victorious. Her hair floated gently behind her, in a wave of her own making.

Lauren Michele Jackson is a doctoral candidate in English at the University of Chicago. She is currently working on a collection of essays about race and appropriation, forthcoming from Beacon Press.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2vYT2EH

Comments

Post a Comment