I suppose there are mathematicians out there “working on prime numbers.” I don’t know if there are. There probably are. They’re putting on coffee at eleven o’clock at night. They’re getting upset at each other on email, cussing. Or adopting “withering tones.” They’re working.

I myself don’t work on prime numbers. I work … on working on prime numbers. Not really. I’ve given the matter some thought. I did work on prime numbers for a few ecstatic days in the year 1999. That was the outcome of more than ten years of brooding. Intermittent brooding. And now it’s been almost twenty years since that. And now I brood over people who brood about prime numbers. I understand them.

I don’t want to explain prime numbers, but I’d better. Let’s at least mix it up. I’ll define prime numbers the way a child does—the way a child has to. Prime numbers are those where, if you had a mass of pencils of that number, you wouldn’t be able to separate the pencils into evenly distributed piles. (One pencil is not a pile, okay?) Like if you have seven pencils. Try to separate ’em into nice even piles.

Ah! doesn’t work! —Prime number.—

I know you know what a prime number is. But there’s a strange pleasure in explaining things like that, over and over. And the existence of that pleasure is meaningful. We’ll come back to it another day.

Once upon a time, I was in college. I had an engineering-major roommate. I loved him, though he was an asshole. As was I. He loved me too. But to get back to my story. He knew all about math and programming and was also a visionary. I was a visionary. We had visions.

Put a straw in a soda. Cover the end with your finger. Take the straw out, the soda stays in the straw. Take your finger off, out comes the soda. So why can’t we make an inverted swimming pool—up into which you would leap—on the same principle? And so on.

I liked to set him teasers. One day it was prime numbers. Look: there’s no space at all between prime numbers two and three. That’s the last time that happens! Between three and five there’s a “space”: the four. Between five and seven there’s a space. But between seven and eleven, uh-oh! Three spaces. Okay. So the question is: How far up the number line do you have to go to encounter a hundred one “spaces” between two prime numbers?

We tried to guess. He had a guess; I didn’t have a guess. He flashed on some kind of equation that would answer the question in no time. Except it didn’t work. Memory says he covered both sides of two pieces of paper with Einstein before his hypothesis was pronounced dead. All this, in 1987. Itself a prime number.

Now skip to also-prime 1999. Brooklyn. Lot of time on my hands. I resolved on getting to the bottom of the matter by brute force. Took a big piece of paper. Wrote out the first thousand numbers. I didn’t have a computer. I took a magic marker, crossed out all the numbers divisible by two. Then by three. Then by five. This system has a name: sieve of Eratosthenes. I’m surprised it has a name; it’s a pretty obvious procedure. Here is a picture of Eratosthenes’s cryogenically preserved head:

I wasn’t really hoping to find that hundred-one-item gap. I just wanted to see what patterns would arise. I was hoping to put myself in a position to venture a guess as to where, more or less, my unicorn was hiding.

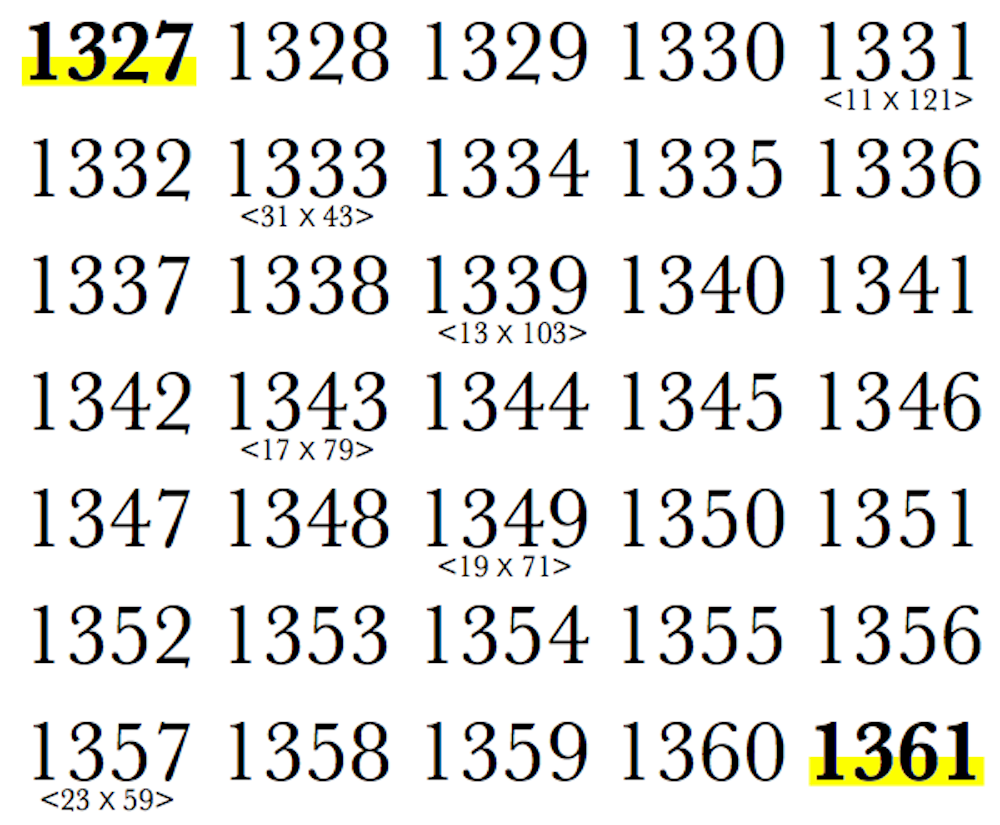

You see where this is going. There was no bloody pattern. I did the whole thing over, starting with two poster-size pieces of paper and a fistful of colored markers. Sieved out all the primes up to five thousand. The largest gap I found was thirty-three “spaces” between the prime numbers 1,327 and 1,361.

The following picture cost me blood—so look at it.

Most of the nonprimes there are divisible by two, three, five, or seven; I have annotated the more exotic cases of nonprimeness, my favorite being 1,333—thirty-one piles of forty-three pencils each. Or, if you like, forty-three piles of thirty-one pencils each.

You should be alarmed, though. That thirty-three-space gap did not occur in the four-thousand-to-five-thousand range. Far from. I don’t even know when the next one occurs. I’d have to go through that sieve nightmare again. Except I wouldn’t, ’cuz there are computers now.

So where would you guess the first hundred-one-space gap occurs? Don’t bother guessing. I’ll just tell you. There are computers now.

It occurs between the prime numbers 1,444,309 and 1,444,411.

Between the numbers two and two million, there are precisely three such hundred-one-space chains. And there are thirty-four of ’em in all if you go to ten million.

Now it has always seemed to me that such gaps must become more and more common if you simply pursue the number line into outer space. Somewhere way, way out there, there must be cases of gaps, not of a hundred one composite numbers but of a billion one. There must even be cases where prime numbers a mile long are posted, slowly rotating in inspissated gloom, a billion one nonprime numbers on either side.

Supreme loneliness. Silence. The darkness of the outer reaches. And no way to get a message to them.

Anthony Madrid lives in Victoria, Texas. His second book is Try Never. He is a correspondent for the Daily.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2KfRVn9

Comments

Post a Comment