1964

This is not the first memory I have of food. My first memory, I believe, was when I ate the Wet-Nap that came in the bottom of a two-piece dinner from Kentucky Fried Chicken just outside the high school football stadium in Sylacauga, Alabama, because I believed it was food. The less we say about that the better.

This is only my first memory of my mother’s food.

And I thought I would die.

I had already been banished from the kitchen, banished from any proximity to the hot stove and sharp instruments. She made me step back even a few steps farther, beyond the door, in case I should suddenly go peculiar and fling myself into the cabbage grater. I had exhibited some unusual behavior already, even beyond the Wet-Nap incident, behavior that made biting into a moistened towelette seem almost humdrum in comparison. I had, after chewing on it like it was gum, somehow poked a plastic poinsettia berry up my nose, requiring medical attention. The less said about that the better, too—though even that should not be strange for the son of a woman who walked around with a marble in her mouth for about three years. I also went crazy at a lumberyard. That time, they said it was probably just sunstroke.

So I stood in the doorway, at a safe distance, and watched her work. The holidays were approaching, and all manner of fine things appeared as if by magic from that little stove. She did not talk to herself then, but she did sing, and over a lifetime of memories of my mother’s cooking, those first days, listening, hold a peace and a warmth I cannot put into the right words no matter how hard I try. I guess the less said about this, too, the better.

Of this day, I mostly remember the smell. Later, much later, I would recognize it as a blend of butter, roasting pecans, melting brown sugar, vanilla flavoring, and more. When she pulled the thing from the oven, she showed it to me, a perfect pecan pie, at or near the top of the pinnacle of what a great Southern cook can do with a dessert.

“It has to sit and cool,” she told me, “and then you can have a piece.”

“How long?” I asked.

“A hour or two,” she told me.

I had a peculiar habit, as a boy, of spinning in a circle when I heard something I did not want to hear.

This time, I damn near went into orbit.

“One HOURRRRRRRR!”

That equated to starvation. I would be down to rag and bones, crawling across the floor, faint and quavering.

“Can’t he’p it,” she said.

“Damn,” I said.

“What did you say?”

I think I shrugged.

“Let me get my belt.”

She had never actually struck me with a belt and would never. But I still harbored some fear of the unknown. I fled. If you did not want your children to learn any new words, you should not let them play in the proximity of pulpwooders or anywhere close to the playground at the Roy Webb Junior High School Halloween Carnival.

One of the first things I had learned about my mother was that although she had the memory of an elephant, her wrath was short-lived, and a lap around the house or a sprint through the cotton field usually took me out of danger. But the smell of that pie kept me in a tight orbit of the house, as if it were calling my name. I circled and circled until I saw her, finally, step out the front door and head down the short walk to my aunt Juanita’s house.

As soon as I saw her reach for the door, I was inside the kitchen, reaching for a knife. I was usually not allowed to touch knives, for fear that I would cut off my own head.

I did not cut a piece. I cut a slab. Half, roughly. Maybe half and some.

I did not take a plate. There was something just wrong about stealing a plate. I cradled the still-hot pie in my hands and sprinted across the backyard and took a hard left turn to the horse pasture and the shed that sheltered a long legacy of poor choices in the selection of Shetland ponies. I settled down behind it, well out of sight, and started to eat.

Lord.

There is nothing else to say about it.

Just …

Lord.

I did not wolf it down. I savored it, trying my best to keep the filling from running through my fingers. It was like trying to eat a very savory puddle of mud. I would learn that this was why you had to let a pie “set.”

I ate it all. I licked my fingers clean. I passed out.

It may be I just had a nap, but when I woke up, I had a little trouble walking a straight line, and I think I was seeing double. I think I was mildly drunk and at the same time talked very, very fast. I had the strength, the energy of a hundred little boys. I giggled, and I hopped. I was so drunk I staggered straight into the house, straight into her.

“What did you do?”

“Et some pie,” I said, and giggled.

I do not recall being beaten then. I guess she figured that pie theft was in my history, in my genes. I do recall that it was quite some time before I could see right again.

She would have liked to present it to us at supper. It deserved that, not to be wolfed down behind a shed by a nitwit.

She just did what she often did.

She sighed.

“Well,” she said, “you can’t have no more.”

Any more and I’d have floated into space.

***

Pecan Pie

WHAT YOU WILL NEED

1 1/2 cups chopped pecans

1 cup brown sugar

1/2 cup granulated sugar

1 stick butter

2 tablespoons flour

2 eggs

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

1/4 cup pecan halves

1 pie shell

HOW TO COOK IT

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees.

Mix everything except the pecan halves and the pie shell. If it seems a little thick, you can thin the mixture with about two tablespoons of water. Then pour it into the pie shell.

Top with the halved pecans in whatever design you wish, or just eat them.

Bake about forty-five minutes, but check it after forty.

Let it set, under guard, for two hours, covered only with a clean cloth. Do not cover it with anything airtight. It needs to breathe.

Some people eat this with ice cream, but that is just crazy talk. “You sure don’t want no more sugar,” my mother believes. “That’s just askin’ for trouble.”

***

I never had a piece of pie that good again, but then my mind was not sound. I believed, for at least part of a day, there was some kind of dark magic in that pie that crossed my eyes and gave me the giggles and set me to staggering and hopping like a fool. My mother said it was probably just sugar; you can get roughly the same effect with a Ding Dong and a large RC Cola. I know. But though I am ashamed to admit thinking this way, it might have been a little better, that pie, because it was illegal pie. I think I know how James, William, and Rodney Rearden felt so long ago when they absconded with pie. I remember all manner of morality tales and fables about boys who stole pie and were hexed, vexed, and haunted, so many and so often that I came to believe that pie thievery must have been a very common thing back then. I would not do it again—it would be unseemly. But sometimes I pass a pie in a bakery, and I wonder. It would probably just taste like pie. But how will I ever know unless …

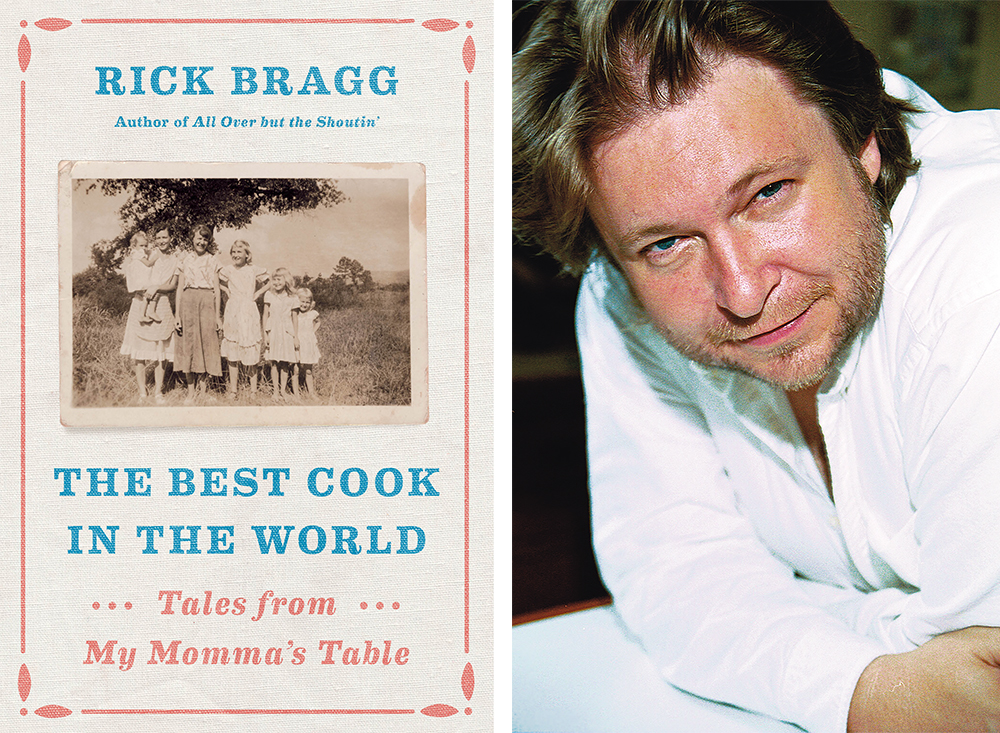

Excerpted from The Best Cook in the World: Tales from My Momma’s Table. Copyright © 2018 by Rick Bragg. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher.

Rick Bragg is the author of seven books, including the best-selling Ava’s Man and All Over but the Shoutin’. He is also a regular contributor to Garden & Gun. He lives in Alabama.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2FazI6R

Comments

Post a Comment