Some of the stories in Rita Bullwinkel’s debut collection, Belly Up, take place in a world that we could call real, and others take place in a world we could call supernatural, but in the hands of a craftswoman like Bullwinkel, both are somehow equal in their strangeness. While reading, I would arrive at the end of a story in which nothing truly paranormal had happened and be nonetheless filled with a sense of disquiet, a sense that I was looking at a photograph of my own world, the light and color settings tweaked ever so slightly. Reality, in Bullwinkel’s hands, is subverted with nuanced strokes of the surreal, in much the same way that David Lynch tilts our perception with his depictions of suburbia. The forms of the stories vary, and Bullwinkel is just as good in a longer, traditional-style narrative as she is in a short, two-page piece of poetic prose. They’re joined by a macabre thread, peopled with dead husbands, teenaged girls obsessed with the idea of cannibalism, and zombies. But even stronger is the sustained interest in the mystery of human connection; a wife tests out a double life after witnessing a fatal car accident and “Phylum” interrogates selfhood and intimacy. As much as Bullwinkel asks us to reconsider the strangeness of our external reality, she asks us to question our internal reality as well; this collection, which absolutely heralds an exciting new talent, takes place at a four-way crossroads between the mind and the body, the reality we can know and the reality adjacent to our own, which we can only glimpse through fiction. —Lauren Kane

In fiction, a character will sometimes wind up on a train platform, pacing back and forth, smoking cigarette after cigarette, deciding whether to stay or to go. This happens in life, too, though I can’t remember hearing an instance of it as dramatic as the one in this past Tuesday’s episode of “The Daily,” the popular New York Times Podcast, about Lam Wing-kee, a bookseller in Hong Kong, who made a career for decades smuggling banned books to customers in mainland China. Reporter Alex W. Palmer explains how Wing-kee figured out how to game the system (shipping into the busiest ports, disguising his products with alternate book jackets), and how, in 2012, when he was taken into custody, he managed to charm and joke his way into being released. Palmer’s article, which accompanies the podcast, starts with a scene in which Wing-kee is detained yet again, in 2015. This time, his jokes aren’t landing with the arresting officers. Xi Jinping has consolidated power, and ordered the government to crack down on this kind of dissent. Wing-kee is taken to a cell in an unknown location. He is held for months. Then follows a surreal scene in a fancy dining room that wouldn’t feel out of place in 2001: a Space Odyssey. From this point on, my pant leg could have caught fire, and I would have dealt with it, while trying to keep my earbuds from falling out. Wing-kee experiences a Joseph Campbell-style moment of reckoning. He must choose between two destinies. I recommend the article for its context, but I would start with the podcast. It tells the story so vividly, you feel like you’re there on the platform with Wing-kee, as he stops pacing, finishes his third straight cigarette, tosses it to the ground, and makes his choice. —Brent Katz

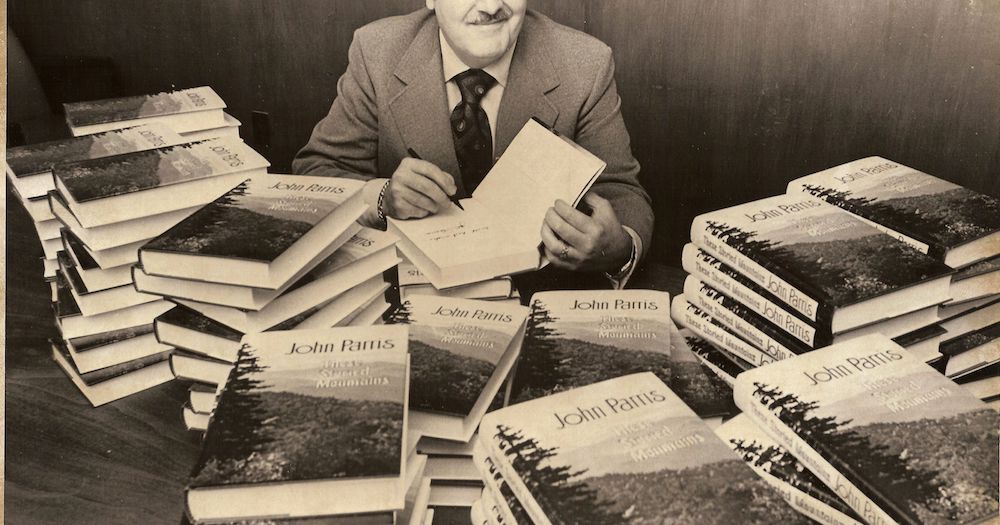

In the early 1950s, John Parris, a well-travelled reporter for the Associated Press who covered World War II, returned to his birthplace in the mountains of Western North Carolina. He spent the rest of his life writing columns for the Asheville Citizen-Times about those mountains, walking them, and collecting stories. A selection of the columns has now been compiled in Walking the Mountains with Joe Parris. He is interested in everything about these mountains, devoting pages to rare mountain sourwood honey and transcripts of learned disquisitions among mountain-folk. The best columns exhibit a beautiful time-slippage—Parris writes of a busy mountain road in 1826 as if it were a week-old piece of journalism, with a snappy lede (“Zacariah Chandler stood in the door of his wayside inn and watched the dust boil up the turnpike”) and short, staccato paragraphs. For Parris, the mountains, amber-like, preserve story in a physical sense. He is aesthetically attentive to the physical beauty and remoteness of the mountains, and his appreciation is inextricable from the people and narratives they conjure. The mountains are Parris’ private, complete cosmos, outside the world and time. A day after discovering his collected columns, I stood at the bottom of the Natanhala Gorge, among Parris’ beloved mountains. The boulder walls, slick and dark, bulged over the river like a mountain range half-folded. The river was green glass, and as I looked up into the mountains I couldn’t help but also see Parris’ scrim of story and talk, actual as rain. —Matt Levin

I am perhaps not among the target audience for Edmund White’s memoir, The Unpunished Vice, because it is the first of his books that I have ever read. I’m all the more ashamed to admit it now that I know the kind of sentences I’ve been missing out on. Take, for instance, the first in the collection: “Reading is at once a lonely and an intensely sociable act.” White leads his readers into his own experiences of reading as well as the life that framed them. To encounter The Unpunished Vice was at once a lonely and an intensely sociable act, the latter not just for the intimacy I felt with White and the characters in his life story, but also for the relationship I learned to recognize between my own favorite reading experiences and all of the parts and people of my life. A reader’s life informs their reading and their reading informs their life. Their reading also informs their future reading. The Unpunished Vice has certainly informed mine—at the very least, by making the top of my reading list all things Edmund White. —Claire Benoit

For the first time in many mornings of being “held temporarily,” I read beyond my stop on the train. It was the fault of an ancient love, Love in the Last Days, a re-telling of Tristan and Iseult by D. Nurkse. I know the story more or less, and I thought I was done with philtres and dragons, but Nurkse’s reimagining makes for beautiful verse. Plenty of poets have taken this reimagining as their task, but Nurkse’s work seems to ask: is a love potion in the woods still compelling poetry? The answer here is yes. “She stared as I struggled with her kirtle,/vissoir and mandemain. Then we were naked. Except for her eyes. I was scared. I’d been naked in combat,/never in love.” Each poem is spoken from a different voice, including a horse whose words are among my favorite. When Tristan sleeps among dogs on the floor of the king’s chamber “Each snored according to his breed […] The kennets and harriers twitched and writhed,/from their thick faint furious cried I deduced/a wounded rabbit, a feist in heat, an adored master.” The lines are lovely, the lovers are doomed, the legend lives, and then you’re sitting in an empty L train at Eighth Avenue long after the doors have opened to release you. —Julia Berick

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2r4zSIR

Comments

Post a Comment