Something shapes people. It’s the world in which they act that makes their experience, that furnishes the economic background that he grows up in and the folkways and the stories that come down to him and his family. It’s the fountainhead of his knowledge and experience. One of the reasons Southerners have this to talk about is that they don’t have much else to talk about—it’s their source of entertainment, besides their source of knowledge. You’ve got the family tales to wile away a long winter evening, and that’s what they have to drawn on, especially in the little hamlets where people sit on the store porch and talk in the evenings. All they have to talk about is each other and what they’ve seen during the day and what happened to so-and-so and also encourages our sense of exaggeration and the comic, I think. Because tales get taller as they go along. It is a pleasure but it’s also something of deep significance to people.

Eudora Welty’s introductory dialogue in the 1977 documentary film Four Women Artists, by William Ferris, is also a metacommentary on the filmmaker himself. Ferris was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1942, grew up on a farm outside town, and began documenting his friends and community at an early age. Between the fifties and the late seventies, he captured—in photographs and on tape and film—the stories, the songs and music, and the spirit of Southern culture during Jim Crow and the fight for civil rights: among his subjects are musicians James “Son Ford” Thomas, Sonny Boy Watson, Lovey Williams, and Fannie Bell Chapman, and writers Barry Hannah, Alex Haley, Alice Walker, and Robert Penn Warren. Best known as a folklorist, Ferris founded, with the filmmaker Judy Peiser, the Center for Southern Folklore, in Memphis, in 1972; in 1979, he became the founding director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi, where he taught for nearly two decades. In 1989, he coedited the Pulitzer Prize–nominated Encyclopedia of Southern Culture and in 1997 was named chair of the National Endowment of the Humanities.

But in 1977, Ferris had the famous Southern writer Eudora Welty on 16mm. And not only Welty, but three other Mississippi artists: Pecolia Warner, a quiltmaker in Yazoo City; Ethel Mohamed, an embroiderer in Belzoni; and Theora Hamblett, a painter in Oxford. Ferris put these four portraits together in the twenty-four-minute film Four Women Artists. Before she was a fiction writer, Welty was a journalist and photographer. “I would see something I thought was self-explanatory of the life I saw,” she says of the images she produced, before reading a portion of her story “Why I Live at the P.O.,” from 1941, in which Welty uses spoken word to drive the narrative. That story was inspired by one of her own photographs, of a woman ironing behind a post office. (“Not that it isn’t the next to smallest P.O. in the entire state of Mississippi,” the story’s narrator complains.)

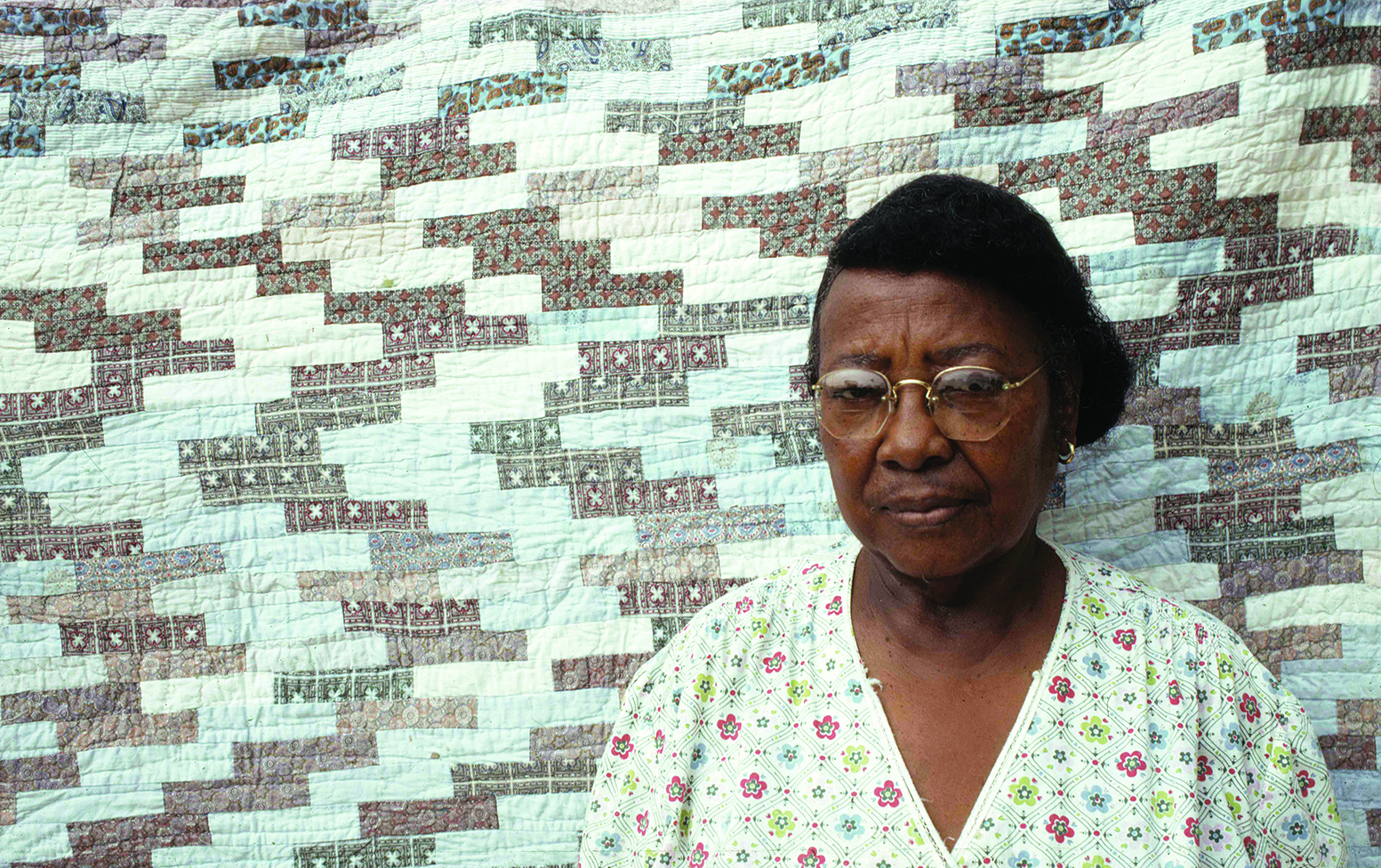

The film’s other women confirm Welty’s introductory claims: that telling tales, through oral and visual culture, is a way of elaborating on and sharing knowledge, experience, and pleasure. Warner offers the best illustration of how this particularly Southern process works. She learned to quilt from her mother—“and if I didn’t do it right,” she explains, “she’d pull it out, make me do it again. She said, If you’re gonna do anything, do it right.” Warner describes observing her mother working on a quilt with seven or eight other women. “While they’re sittin’ there,” she recalls, “they’d get to talkin’ about religion and talkin’ about the Bible and all that and they’d get happy and commence to crying and I’m layin’ up under the table, watchin’ ‘em.” Warner relates this story on camera when she is seventy-three—older than her mother would have been in the memory—as she sits around a quilt with several younger women as her audience.

We’re pleased to premiere Four Women Artists here. The film will be released on June 1 as part of Voices of Mississippi, a CD/DVD/book set of featuring blues and gospel recordings, interviews, and documentary films by Ferris—an archive of his life’s work. —Nicole Rudick

Nicole Rudick is managing editor of The Paris Review.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2seUD5a

Comments

Post a Comment