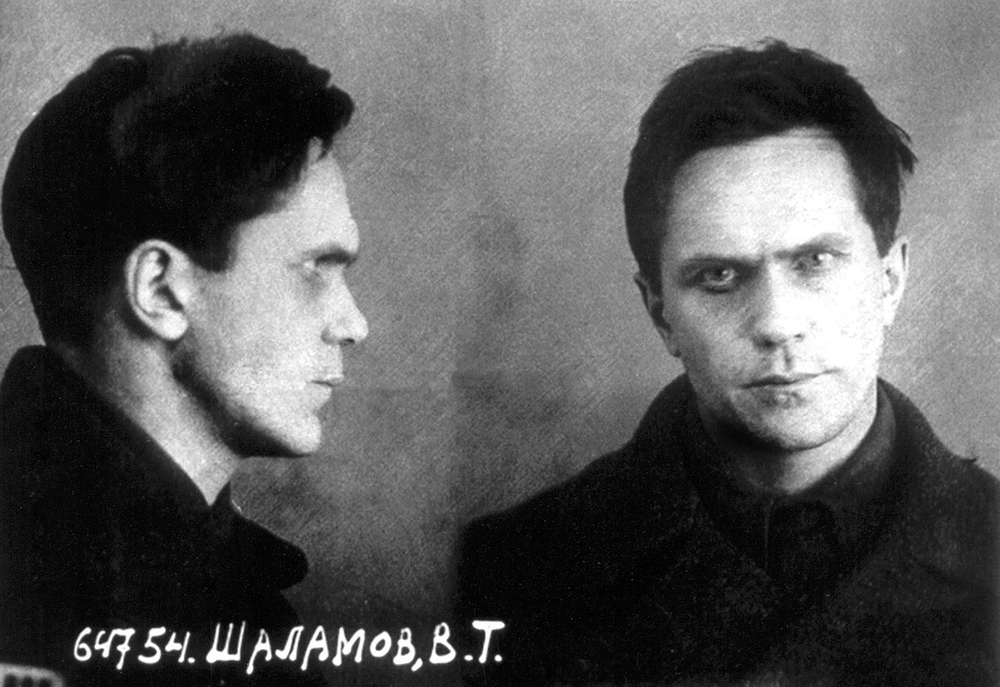

For fifteen years the writer Varlam Shalamov was imprisoned in the Gulag for participating in “counter-revolutionary Trotskyist activities.” He endured six of those years enslaved in the gold mines of Kolyma, one of the coldest and most hostile places on earth. While he was awaiting sentencing, one of his short stories was published in a journal called Literary Contemporary. He was released in 1951, and from 1954 to 1973 he worked on Kolyma Stories, a masterpiece of Soviet dissident writing that has been translated into English for the first time and published by New York Review Books Classics this week. Shalamov claimed not to have learned anything from Kolyma, except how to wheel a loaded barrow. But one of his fragmentary writings, dated 1961, tells us more.

1. The extreme fragility of human culture, civilization. A man becomes a beast in three weeks, given heavy labor, cold, hunger, and beatings.

2. The main means for depraving the soul is the cold. Presumably in Central Asian camps people held out longer, for it was warmer there.

3. I realized that friendship, comradeship, would never arise in really difficult, life-threatening conditions. Friendship arises in difficult but bearable conditions (in the hospital, but not at the pit face).

4. I realized that the feeling a man preserves longest is anger. There is only enough flesh on a hungry man for anger: everything else leaves him indifferent.

5. I realized that Stalin’s “victories” were due to his killing the innocent—an organization a tenth the size would have swept Stalin away in two days.

6. I realized that humans were human because they were physically stronger and clung to life more than any other animal: no horse can survive work in the Far North.

7. I saw that the only group of people able to preserve a minimum of humanity in conditions of starvation and abuse were the religious believers, the sectarians (almost all of them), and most priests.

8. Party workers and the military are the first to fall apart and do so most easily.

9. I saw what a weighty argument for the intellectual is the most ordinary slap in the face.

10. Ordinary people distinguish their bosses by how hard their bosses hit them, how enthusiastically their bosses beat them.

11. Beatings are almost totally effective as an argument (method number three).

12. I discovered from experts the truth about how mysterious show trials are set up.

13. I understood why prisoners hear political news (arrests, et cetera) before the outside world does.

14. I found out that the prison (and camp) “grapevine” is never just a “grapevine.”

15. I realized that one can live on anger.

16. I realized that one can live on indifference.

17. I understood why people do not live on hope—there isn’t any hope. Nor can they survive by means of free will—what free will is there? They live by instinct, a feeling of self-preservation, on the same basis as a tree, a stone, an animal.

18. I am proud to have decided right at the beginning, in 1937, that I would never be a foreman if my freedom could lead to another man’s death, if my freedom had to serve the bosses by oppressing other people, prisoners like myself.

19. Both my physical and my spiritual strength turned out to be stronger than I thought in this great test, and I am proud that I never sold anyone, never sent anyone to their death or to another sentence, and never denounced anyone.

20. I am proud that I never wrote an official request until 1955.

21. I saw the so-called Beria amnesty where it took place, and it was a sight worth seeing.

22. I saw that women are more decent and self-sacrificing than men: in Kolyma there were no cases of a husband following his wife. But wives would come, many of them (Faina Rabinovich, Krivoshei’s wife).

23. I saw amazing northern families (free-contract workers and former prisoners) with letters “to legitimate husbands and wives,” et cetera.

24. I saw “the first Rockefellers,” the underworld millionaires. I heard their confessions.

25. I saw men doing penal servitude, as well as numerous people of “contingents” D, B, et cetera, “Berlag.”

26. I realized that you can achieve a great deal—time in the hospital, a transfer—but only by risking your life, taking beatings, enduring solitary confinement in ice.

27. I saw solitary confinement in ice, hacked out of a rock, and spent a night in it myself.

28. The passion for power, to be able to kill at will, is great—from top bosses to the rank-and-file guards (Seroshapka and similar men).

29. Russians’ uncontrollable urge to denounce and complain.

30. I discovered that the world should be divided not into good and bad people but into cowards and non-cowards. Ninety-five percent of cowards are capable of the vilest things, lethal things, at the mildest threat.

31. I am convinced that the camps—all of them—are a negative school; you can’t even spend an hour in one without being depraved. The camps never gave, and never could give, anyone anything positive. The camps act by depraving everyone, prisoners and free-contract workers alike.

32. Every province had its own camps, at every construction site. Millions, tens of millions of prisoners.

33. Repressions affected not just the top layer but every layer of society—in any village, at any factory, in any family there were either relatives or friends who were repressed.

34. I consider the best period of my life the months I spent in a cell in Butyrki prison, where I managed to strengthen the spirit of the weak, and where everyone spoke freely.

35. I learned to “plan” my life one day ahead, no more.

36. I realized that the thieves were not human.

37. I realized that there were no criminals in the camps, that the people next to you (and who would be next to you tomorrow) were within the boundaries of the law and had not trespassed them.

38. I realized what a terrible thing is the self-esteem of a boy or a youth: it’s better to steal than to ask. That self-esteem and boastfulness are what make boys sink to the bottom.

39. In my life women have not played a major part: the camp is the reason.

40. Knowing people is useless, for I am unable to change my attitude toward any scoundrel.

41. The people whom everyone—guards, fellow prisoners—hates are the last in the ranks, those who lag behind, those who are sick, weak, those who can’t run when the temperature is below zero.

42. I understood what power is and what a man with a rifle is.

43. I understood that the scales had been displaced and that this displacement was what was most typical of the camps.

44. I understood that moving from the condition of a prisoner to the condition of a free man is very difficult, almost impossible without a long period of amortization.

45. I understood that a writer has to be a foreigner in the questions he is dealing with, and if he knows his material well, he will write in such a way that nobody will understand him.

From Kolyma Stories by Varlam Shalamov. Translation and introduction copyright © 2018 by Donald Rayfield. Courtesy of NYRB Classics

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2MkD104

Comments

Post a Comment