In bed some nights, too tired to read, I lie on my side with my phone plugged into the wall and scroll through Instagram. Lately, perhaps because of the algorithms, process videos of illustrators painting have risen to the top of my feed. My favorites are the ones where the artist begins without a drawing, the canvas blank as a sheet; I like the mystery of the movement of the brush, following its slow dance across the paper. After thirty seconds, a minute, the strokes come together, and on the glowing screen an image rises up, like an omen out of water. A face, a flower, a still life. I could watch them all night, and often do, mesmerized by the startling process of creation.

The drawings at the center of Marlene Dumas’s current show at the David Zwirner gallery, Myths and Mortals, take their subject from Shakespeare’s poem “Venus and Adonis.” That poem is itself a retelling of Ovid’s Venus and Adonis, which is itself one iteration of a classic myth told around fires long before Ovid wrote it down. In this story, Venus, the goddess of love, has helplessly fallen for a young mortal hunter, Adonis. How impossible that the goddess of love could be a victim of love herself—and yet. Pricked by Cupid’s bow, she succumbs. Overcome by passion, desire courses through her body, making her cheeks pale and the sweat stand out on her brow.

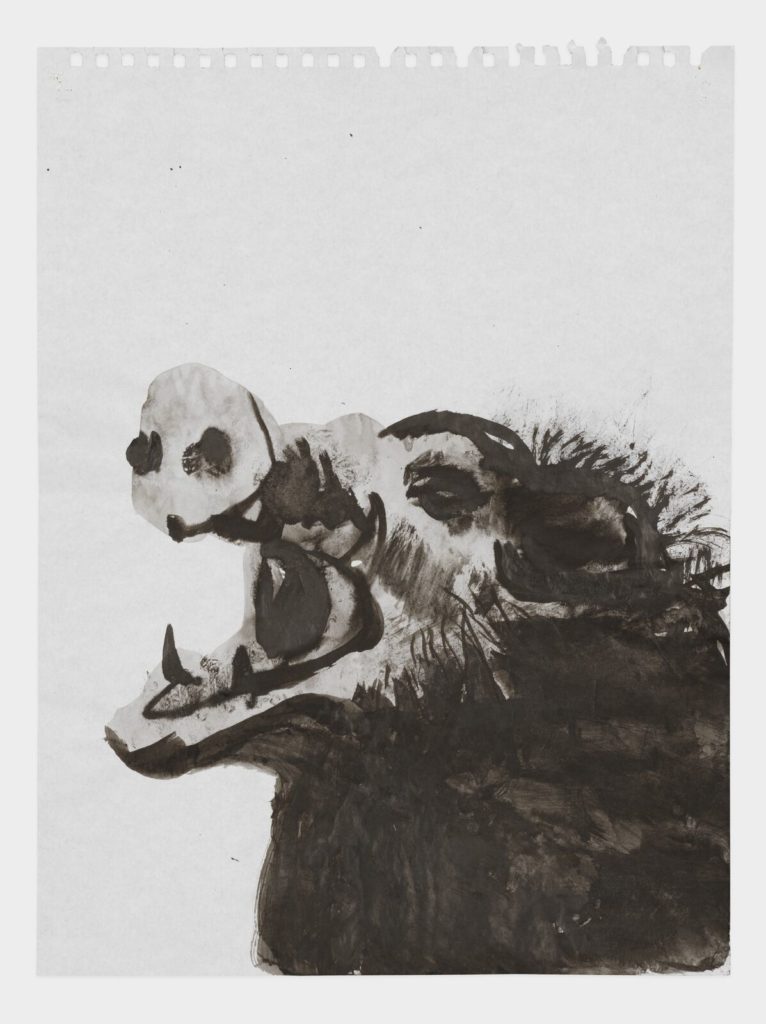

Venus begs and pleads with Adonis to return her ardor, coaxing him with sweet words and flattery; when that doesn’t work, she straddles him, her body close to his, entreating him to kiss her. But Adonis simply frowns at her. Like some kind of a classical fuckboy, he claims no desire for desire. Though the two lovers eventually share a brief embrace, all Adonis craves is the hunt. Knowing that he’ll die if he goes, Venus begs Adonis not to hunt the wild boar. But he ignores her warning, and the boar attacks him, driving its tusks deep into his groin.

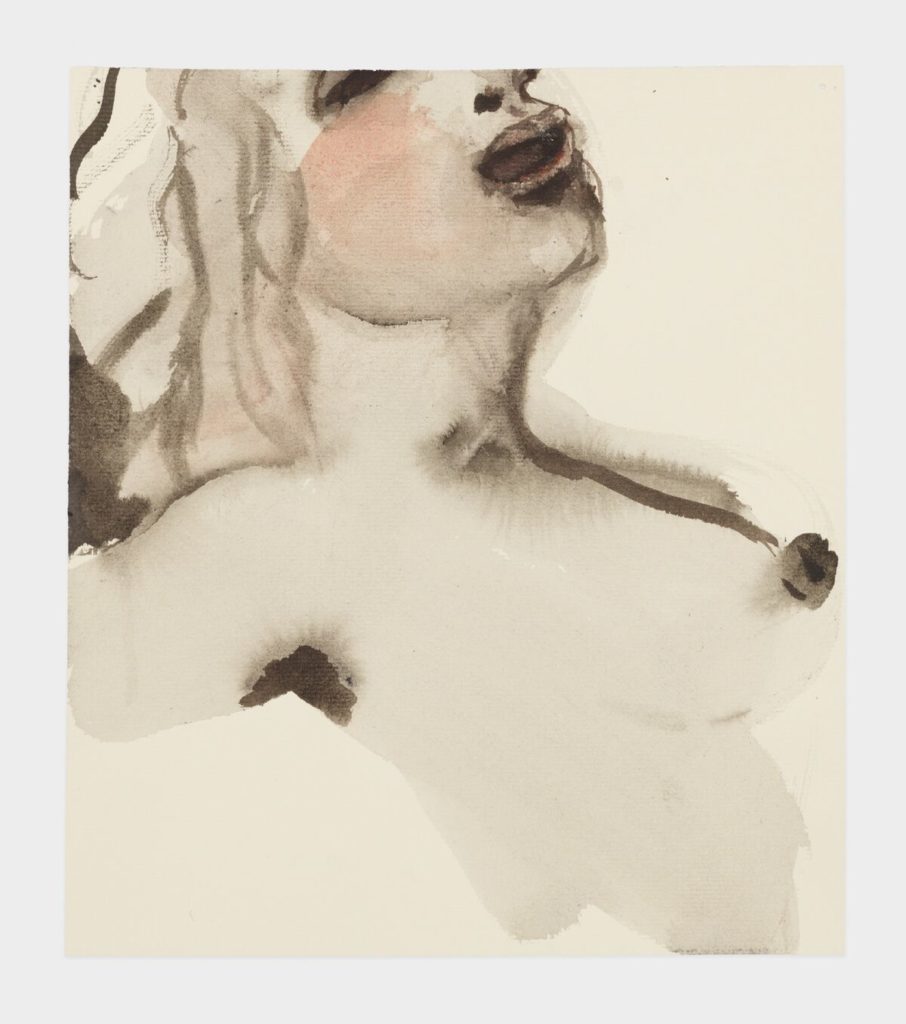

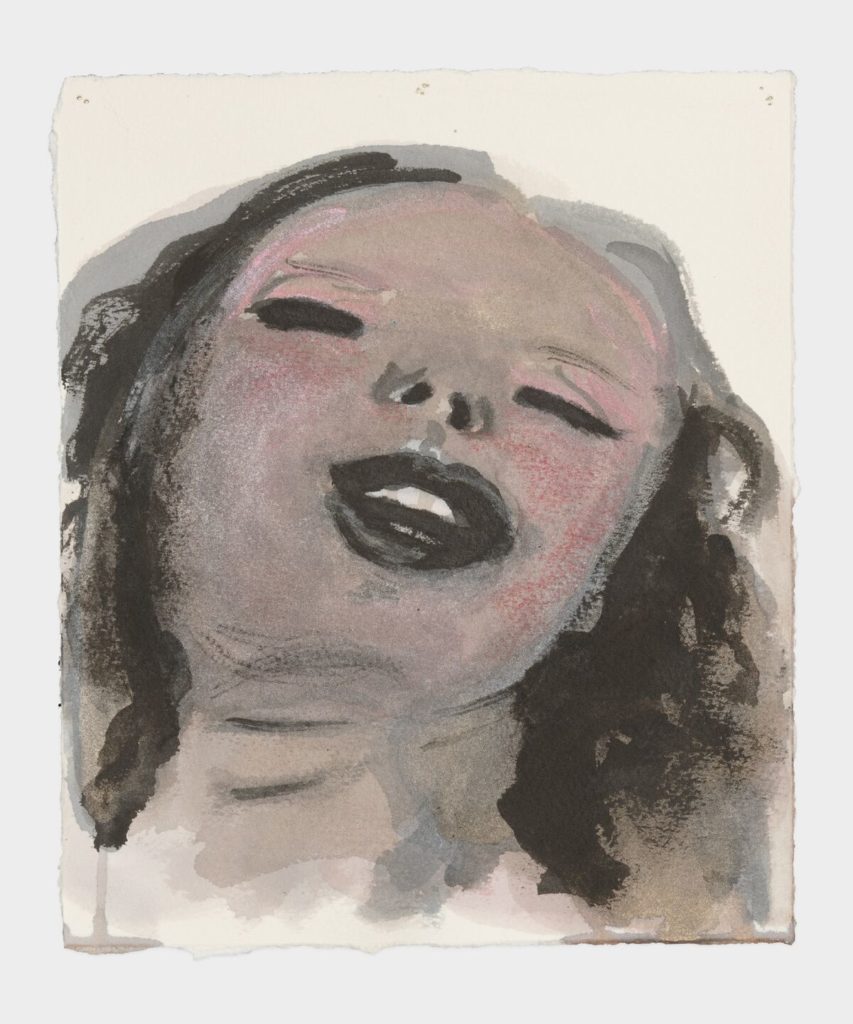

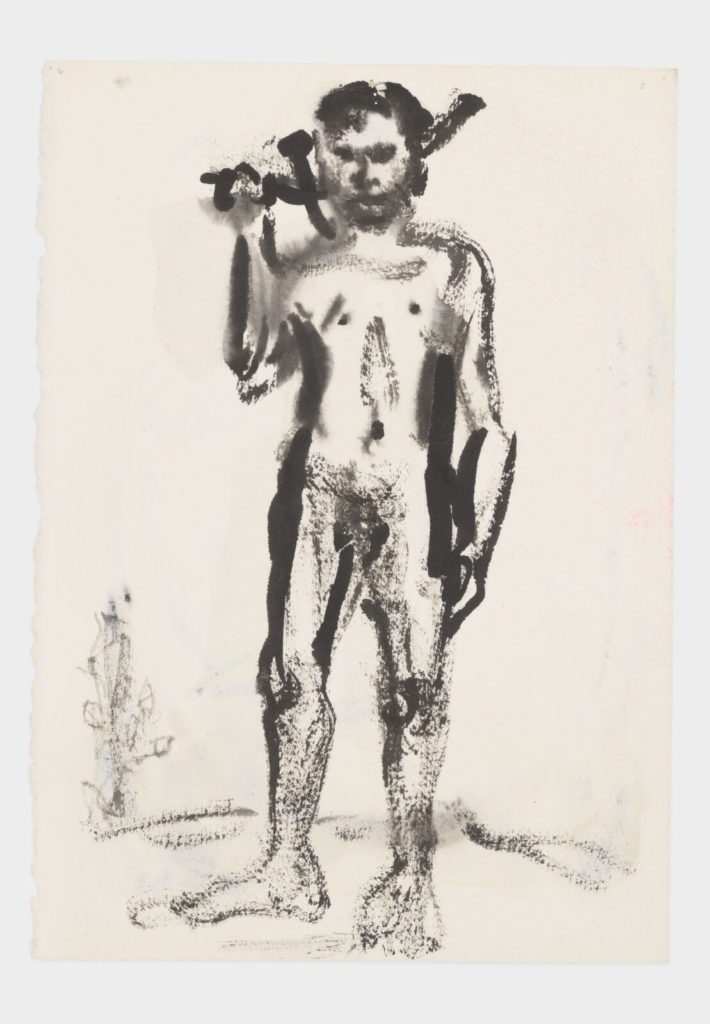

In Dumas’s rendering, Venus becomes a coy, fleshy nude, a woman in love like any other. Her face is mobile and overcome by various passions—bliss turns her cheeks pink; infatuation sees her chatty and mirthful. Love makes her suspicious, nearly feral and hunted herself, her eyes saturated with ink, her mouth darkened as if with wine. Meanwhile, Adonis is a handsome youth, the fine bones of his face jumping with clarity out of loose brush marks. His carefully drawn features underscore his improbable good looks. For us to buy in to the dramatics of the narrative, Dumas understands, we must properly comprehend both Adonis’s beauty and Venus’s desperation. These are the hinges from which the story swings open, like a clamshell. The lovers’ embraces, alternatively passionate and tragic, are composed of thin washes of ink, their bodies emerging from one brushstroke like a shadow cast by two separate objects. The drawings, almost three dozen in all, are uniformly wet and loose.

Crouching over Adonis’s corpse, Venus weeps bitterly, singing a dirge, and before her very eyes, his blood, which wells out of his wounds and has soaked the forest floor, blossoms and turns into a flower—purple in some translations, and red in others. In Dumas’s hands, this flower has petals of both hues, and grows alone in a gray fog, its edges indefinite and blurry with water. It is a blossom both romantic and morbid, a symbol of love’s ravages.

*

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, things are always turning into other things by dint of fate, or failure, or desire. To avoid the lustful pursuit of Apollo, Daphne turns into a laurel; Ariadne, abandoned by Theseus on the island of Naxos, is seduced by Bacchus and thrown up into the night sky, where her crown becomes a constellation. Pygmalion’s sculpture is brought to life and he marries her; Actaeon, startling the goddess Diana at her bath, is transformed into a deer and killed by his own hunting dogs. “In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas / corpora,” Ovid begins his epic. Translations vary, but roughly: “Now I will speak of forms changed into new bodies.” The moral of metamorphosis is unclear: mortals are not transformed according to their character. There may be no lesson in Ovid’s text—only the upheaval promised by a life lived so close to the gods, and the assurance that change is both immanent and unpredictable.

Dumas’s work is characterized by a somber palette—black, gray, acidic pinks and beiges—and a looseness of hand that allows her images to slide into incomprehension. It’s not so unlike a kind of transfiguration, too—the picture emerging amid burbles of turpentine. Her ink drawings in particular seem suddenly formed, as if from a few unintentional gestures that despite themselves produced meaning. Faces and bodies arise from blobs, pulled out from indefinition by dry-brushed strokes; mouths and nostrils have the feathered edges of ink dropped onto wet paper. Looking at her drawings one by one, circling the perimeter of a room, I wonder how she knew—what mark to make, when to let gravity and accident take over. Which came first: the blot or the image? Or did she make the mark in the image’s name? I want to know; I put my face close to the pictures to look. It’s like considering the construction of a flower.

*

How strange to realize that everything made begins as a blank page. Or—not always; one of the last drawings in Dumas’s series, “The wound becomes a flower,” is on the back of a printout. I tried to read the text backwards through the image, but still don’t know what it said. I like to think of her in her studio, so caught up in the work that she reached for the closest possible surface, ignoring the way printer paper isn’t meant to be painted, the way it balls up in response to too much water.

I used to paint, then I stopped. Four years later, I started again. Despite almost a decade of keeping muddy brushes jammed into jars of turpentine, I never know how to begin a thing. It always seems like I take the brush in hand, black out, and two hours later, there’s something before me that I can work with and name. That’s not to say that there’s no craft involved in art-making—to view Marlene Dumas’s work is to witness a woman who can draw the hell out of a portrait but chooses not to, only selectively tightening her hand. But it’s more that first incoherent spark I’m interested in, that moment between wanting to make and understanding what you’re making. Turning the corner from formlessness into form. I once went to a reading where, during the Q&A, someone asked the panelists, “Where do you get your ideas?” and I scoffed from my seat all the way in the back. What a funny question, as if there’s an idea tree that gives fruit. But it’s an earnest one.

There’s always a moment of transformation in the process of making. Suddenly you understand what your novel is about, or what a short story hinges on, or what you’re trying to say in a poem. I love talking to people about that moment, the moment where they knew. It’s like when lightning strikes—another gesture beloved of the gods—and all the trees in a field jump out in stark relief, their leaves hot white and glowing. But the trees weren’t created in that moment: they were there all along. There are objects in a dark room. A light bulb just allows us to see them.

How does the thing in my head become the thing that you are now reading? Who is walking down that dark hallway, turning on all the lights? Art is mostly incomprehensible, and yet it exists. There are ways to make, but how to begin the making? We keep trying. When it’s hard, and it often is, I wonder if it helps to think of it not as creation out of whole cloth but a kind of transfiguration. Actaeon, a deer now, running around. To consider that perhaps our works of art were here all along, hidden within.

In the last drawing of the sequence, Dumas draws not a god nor a mortal but a dove, one of the flock who pull Venus’s chariot and take her away from her true love’s corpse. The dove’s body is formed from one fluid mark, its wings another brushy stroke. Something—a spirit?—spews out of its round body, as if forcibly ejected; it runs where it encounters the edge of the frame. The ink wash is laid down flat, darkening at the bottom where the pigment has pooled. On its own, the ink looks like an accident, a drip or a spill from an over-enthusiastic artist. But Dumas has sharpened the bird out of the fog by delicately drawing its head: the meager outline of its beak, its shining eye, the few, fine lines. This is all the image needs to become.

Marlene Dumas’s “Myths & Mortals” is on view at the David Zwirner gallery until June 30th

Larissa Pham is a writer in Brooklyn.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2yraJ0L

Comments

Post a Comment