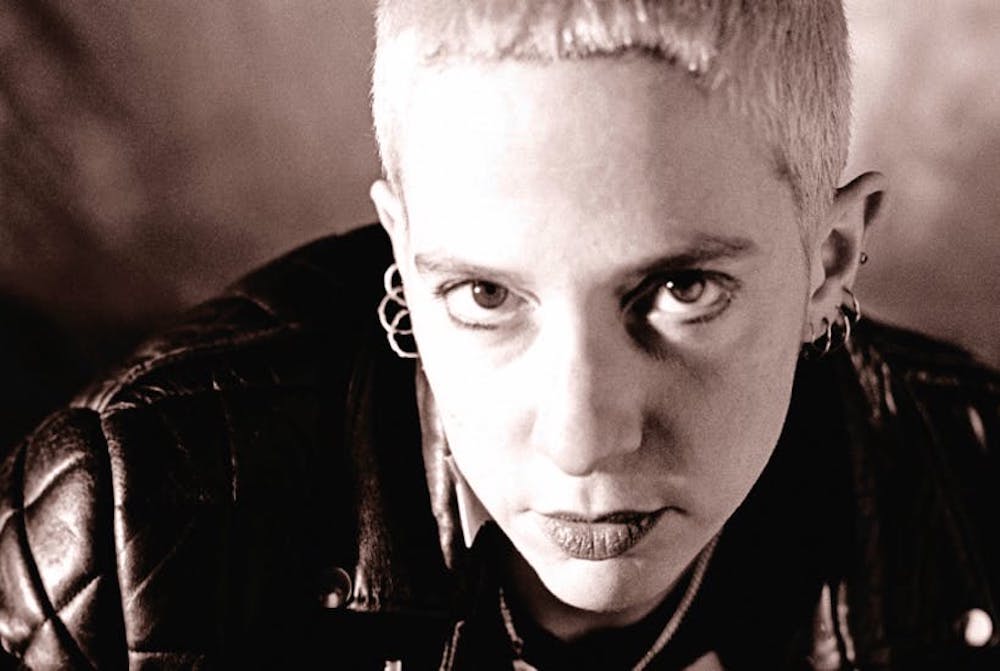

“I make nothing new, create nothing: I’m a sort of mad journalist,” Kathy Acker writes in 1989, on Empire of the Senseless, her fifth book from a major publisher and first venture into the realm of science fiction. At first glance, journalism seems an odd analogy for this work, an obscene and mind-bending saga set in the shadow of Reagan’s presidency and told from the alternating perspectives of Thivai, a pirate, and his intermittent lover, a half-human, half-robot woman named Abhor. But even as the novel extends into a speculative near future—where Paris has been overrun by Algerian rebels and the CIA conducts clandestine operations to turn this chaos to their strategic advantage—it remains insolently rooted in the world in which we belong, anchored by Acker’s stubborn commitment to rendering visible the sexist, racist, capitalistic, father-fucking societal ego of her time—and of our own. Kathy Acker is a muckraker in the original sense, one who dredges up the dirt and puts it on display to the delight and horror of the reading public.

“Knowing much information and not feeling anything doesn’t get you anywhere,” a terrorist tells Abhor early on.“The answer to your question is that democracy doesn’t get you anywhere.” As heterodox as Acker may be in form and structure, this novel is concerned with elemental political questions: How should we navigate the nowhere of the present, and where else is there to go? Empire was written within what Acker calls a “post-cynical” period in American society, where faith in the sanctity of middle-class white domesticity had been displaced by post-Watergate disillusionment. She felt little need to further explain why or how or in what way society was rotten and gravitated instead toward the utopian, in the older, archaic sense of the term: an elsewhere, a reality deferred. The elsewhere she crafts is equal parts Neuromancer, Story of the Eye, and Huckleberry Finn, a slurry of histories that points the way to a future, another way to be. “We now have to find somewhere to go, a belief, a myth,” Acker wrote. “Empire of the Senseless is my first attempt to find a myth, a place, not the myth, the place.”

This mythic register offers an unnostalgic, irreverent alternative to the impasses of reality. Empire opens into “Elegy for the World of the Fathers,” a description of the dominant order, a twisted ode to the Oedipal myth and to a world in which “the rich who have suicided in life are taking us, the whole human world, as if they love us, into death.” Through Thivai, we get an account of Abhor’s childhood and family history that is as bleak as can be: the police’s abuse of her grandmother, her father’s coming-of-age as a charming and brutal alpha male, followed by an elaborate, Sadean summary of Abhor’s serial rape at the hands of her father, a man who “got married because he wanted to propagate himself once.” To propagate, to make new within the paternalistic model, is an Ackerian dead end, one old idea producing another.

Father-rape metonymically stands for the whole of the capitalistic world order, a world structure that collapses over the course of the novel, but fails to wholly disappear. Although the World of the Fathers recedes and Abhor never again encounters her own within the fictive present of the book, the father figure returns in different guises—the mad doctor Shreber, the bloodthirsty revolutionary Mackandal, even Thivai himself demonstrates a fatherly possessiveness toward Abhor, a capitalist’s view of woman as property. In the novel’s second and third movements, the authority of this dominant world order weakens, and struggle between Muslim and Western forces overtakes Paris, culminating in a fragile, dystopic openness, a “ruined suburbia” that Thivai experiences as a form of freedom. But the revolution is patchy, its arc fractured: the future is struggle, and Abhor finds herself liberated from the world of bosses only to end up trapped by other, unforeseen men.

Terms like post-apocalyptic and dystopian are too tidy for Acker’s project, which aims to draw attention to the squalor of the civilized and the unfinished, ongoing process of world-death. Instead of seeing ends, we see horizons: swathes of world that shade off into the distance and finish somewhere out of view. Acker uses the scaffolding of the science fiction novel in the same way a looter might use a rock to bash in the window of a supermarket—a convenient tool to access someplace interesting.Though it drew inspiration from the work of genre-establishing friends like William Gibson, Empire eschews conventions of science fiction world-building in favor of a visceral sense of immediacy. A luminous, transfixing description of Abhor’s cyborg body is not there to help illustrate some alternative technocratic world order, but to draw the reader out of their fixed place and into another:

A transparent cast ran from her knee to a few millimetres below her crotch, the skin mottled by blue purple and green patches which looked like bruises but weren’t. Black spots on the nails, finger and toe, shaded into gold. Eight derms, each a different colour size and form, ran in a neat line down her right wrist and down the vein of the right upper thigh. A transdermal unit, separated from her body, connected to the input trodes under the cast by means of thin red leads. A construct.

Because the more futuristic elements of the narrative estrange and displace rather than unfurl a whole and coherent picture, the world Abhor and Thivai inhabit is oddly constituted—it shimmers like a hologram, a hallucination.When viewed from one angle, it remains a recognizable collage of miseries and drab pleasures, a mirror of our own times. But viewed from another, it possesses an alien sheen, the sense of a non-patriarchal, non-phallic newness.The gap between these two visions invites the reader to plug in and complete the picture, to suture together the feelings that thrust the story forward. The myth of succession breaks down in Empire, ends and beginnings comingle and ultimately bleed into one another: Apocalypse is a leaky, incomplete thing.

“Writing must be a machine for breaking down, that is, allowing the now uncontrolled and uncontrollable reconstitutions of thoughts and expressions,” Acker once wrote. What should the reader do with a book like this, a book that doesn’t behave, that won’t sit still and simply make sense? A book that refuses to imagine either the indefinite prolongation of our world or its definitive replacement by another, a book that rejects easy endings and false beginnings, a book that equally ignores formulas of plot and formulaic thought. What’s bold about Empire of the Senseless isn’t the premise that the world we know could end and another one could take its place—that story has been told many times before. Instead, it’s the fictive space that Acker allows the reader to explore, a vitally unfamiliar elsewhere that serves as a source of anger and exuberance as well as the apprehension that things could be other than how they are. So don’t just read this book, use it—as a tool, a hammer, a rock to smash in whatever barrier prevents you from imagining another, better place. Literary texts participate in real-world consequences. As the author herself declared: “If a work is immediate enough, alive enough, the proper response isn’t to be academic, to write about it, but to use it, to go on. By using each other, each other’s texts, we keep on living, imagining, making, fucking, and we fight this society to death.”

Alexandra Kleeman is the author of the novel You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine and the story collection Intimations.

Excerpted from Empire of the Senseless, by Kathy Acker. Introduction copyright © 2018 by Alexandra Kleeman. Published by arrangement with Grove Atlantic.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2y52XJV

Comments

Post a Comment