After eight years as managing editor, and editing the last two issues as interim editor, Nicole Rudick has decided to leave The Paris Review. Our staff is small, and Nicole’s role, like so many of ours, extended far beyond that which is simply captured by job titles: she promoted new writers and artists, curated portfolios and conducted interviews for the magazine, edited and wrote pieces for the Daily, produced special projects—like our reinvigorated Paris Review Editions imprint and the Big, Bent Ears series—and so much more. We’ll miss her dry humor, strongly held opinions, hard-earned praise, and surprisingly colorful dress shoes. She has been equal parts tough and nurturing, a mentor to many who have passed through these doors. The day after the 2016 election, when many of us were crying quietly at our desks, Nicole gathered everyone around the pool table for a meeting. Then she turned on the music and encouraged us to dance.

Below, a very small sampling of the contributions Nicole has made to the magazine over the years:

Jane Smiley, The Art of Fiction No. 229

Issue no. 214 (Fall 2015)

Jane Smiley grew up in Webster Groves, Missouri, in a family of storytellers—and it shows. During the two afternoons I spent interviewing her, I heard about how her great-grandmother, a Norwegian immigrant, met her husband while going door-to-door as a dressmaker in Saint Paul, Minnesota; how her grandfather nearly froze to death during a blizzard on an Idaho ranch; how her grandmother lost the diamond ring her husband had won in a poker game. One anecdote led to another, and she frequently interrupted herself to ask, “Did I tell you about … ” before launching into a story within a story, a pattern that continued as she made scones, cooked dinner, fed her horses, and drove.

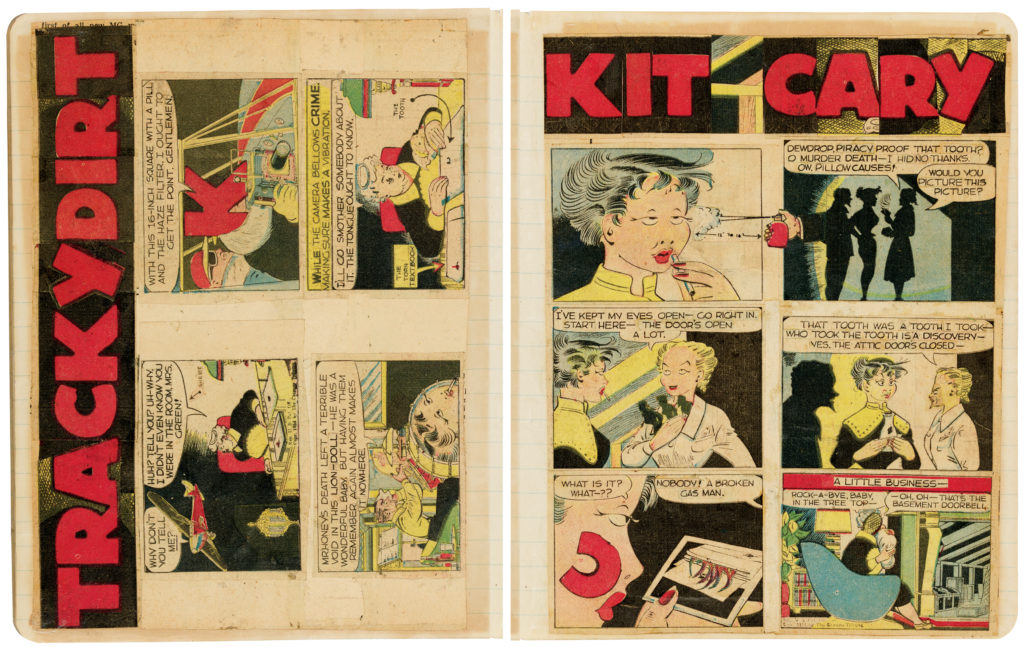

“Paste-ups” by Jess

Issue no. 202 (Fall 2012)

As a boy, Jess—born Burgess Collins in 1923—saw the Watts Tower under construction and “filed this salient experience away for later sustenance.” It wouldn’t stay filed for long. After a stint as a radiochemist for the Manhattan Project, he exchanged the laboratory of science for one of art, producing paintings, paste-ups (his preferred term for collages), and assemblages full of unlikely juxtapositions. “If it’s unexpected,” Jess advised the viewer, “expect it.” By 1951, he had become an integral member of the Bay Area’s underground art scene and had embarked on an artistic and romantic partnership with the poet Robert Duncan that would last four decades.

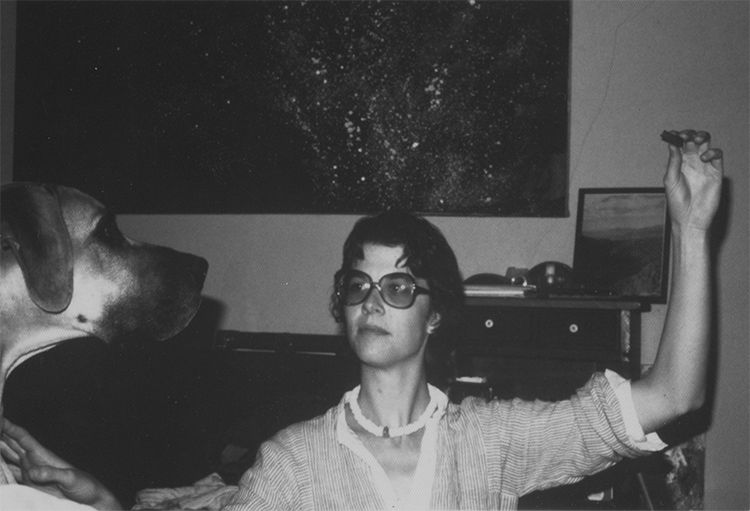

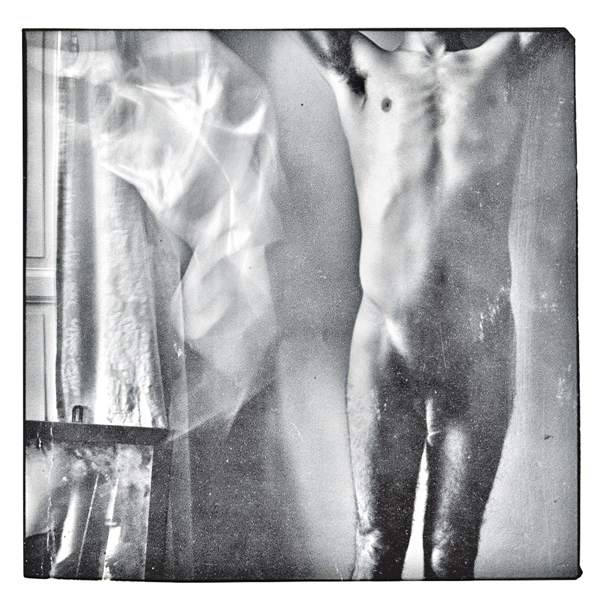

“Fugitive Photographs” by Francesca Woodman

Issue no. 208 (Spring 2014)

All of Woodman’s work is early work—she committed suicide in 1981, at the age of twenty-two—but even this small cache contains surprising discoveries. Among these “lost” photographs is a male nude, rare in Woodman’s work; the model was her then-boyfriend, Benjamin Moore. In the photograph, he stands with his arms raised, ribs exposed, next to a blurred form that seems to mimic his skeletal structure. Moore revealed to Schor that this ghostly effect, which appears elsewhere in her work, was created rather ingeniously: Woodman stood on a ladder, her body out of the frame, and crumpled a piece of paper in front of the camera during a timed exposure.

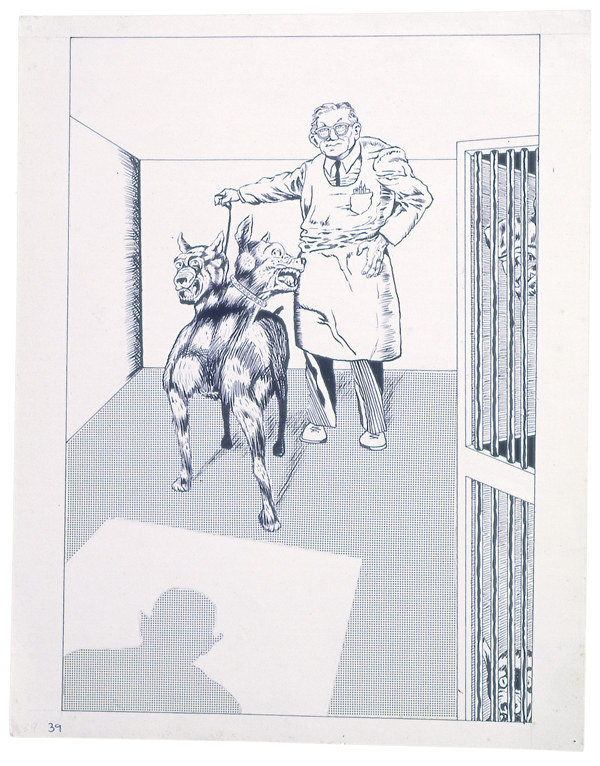

“Real Dogs in Space” by Raymond Pettibon

Issue no. 209 (Summer 2014)

Boo is a frequent muse for Pettibon—her portrait graces the cover of this issue, and she appears, in various guises, throughout this selection of drawings—but then dogs are everywhere in his art. Dobermans and Dalmatians are regular favorites: the former because they’re so recognizable that, he argues, you don’t have to draw the whole dog; the latter because their distinctive markings are visually interesting within Pettibon’s black-and-white palette (“it’s like doing a zebra”).

Invisible Adventure: Watching a Film About Claude Cahun

The Daily (December 9, 2015)

The film opens on a shot of a small folded card that contains the handwritten phrase “L’aventure invisible.” Pierson picks up a zoetrope next to the card and sets it spinning. As the images gain momentum, the woman inside begins to move. We see her in a succession of costumes—in men’s clothing, in a black dress with a yellow star, as a weight lifter, a Buddha, an angel; she postures and poses, thumbing her nose, crouching, bending on one knee. Though the short film, which is also titled Zoetrope, is silent and doesn’t tell us who the character is, I know that it is Claude Cahun, a little-known French Surrealist artist, writer, and provocateur who made work with her lover, Marcel Moore, both before and during World War II.

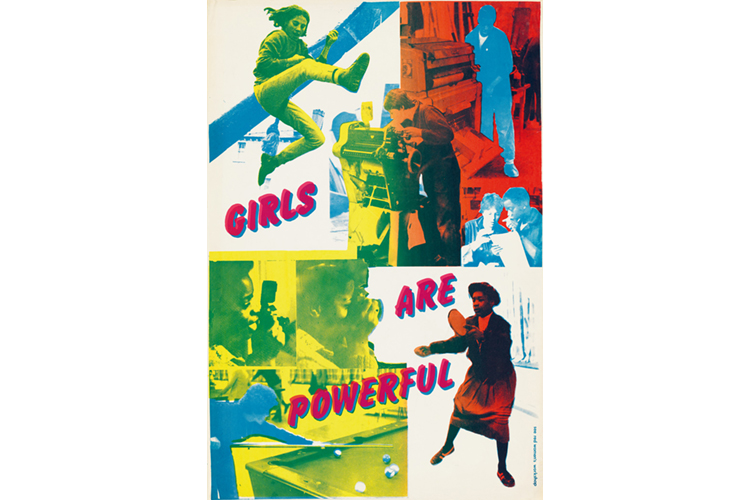

Women Hold Up Half the Sky

The Daily (March 8, 2017)

In 1974, a group of women answered an ad calling for those in the visual arts to gather to help promote the women’s liberation movement and counter the prevailing negative images of women in advertising and the media. Like many women at the time, the members of See Red were disillusioned with the Left; the story they relate is an old one: “We found ourselves marginalized within these campaigns and were expected to stay in the background, keep quiet and make the tea.” The members worked collectively and non-hierarchically: from idea to concept to design to production, decisions and process were undertaken as a group.

And of course:

The Paris Review Issue No. 224 (Spring 2018)

The Paris Review Issue No. 225 (Summer 2018)

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2zeYuF3

Comments

Post a Comment