On memory, inherited trauma, and my grandmother

When I was almost two years old, my grandmother flew from Hongcheon, South Korea to Flushing, Queens to take care of me. For a few years, while my parents worked, I spent my hours with Halmuni. I do not remember how we colored our days, but I press my thumb onto the photographs of that time. I smudge their borders and try to return to a forgotten past.

In one glossy, blurry photograph, I am paper-crowned with a waxy, yellow Burger King wrapper laid out before me, a rounded bun raised to my open mouth. Halmuni does not eat; instead, the camera catches her watching me. A tender, unsmiling gaze. When I examine this picture, I am convinced I remember. That crown, I think. Yes. I remember the thick gold paper with the Burger King logo, the jewels on the rounded arches. But the crown in the photograph is blue, and that unexpected color unbalances me. My confidence slips. Perhaps I am remembering a different day. Perhaps I am remembering the last time I looked at this photograph. Memory warps and stretches and shifts to fit the strictures of your life.

As my mother and I share a bottle of wine, she recalls my first years. She tells me that I had no understanding of mother-daughter love when I was young, that my world revolved around Halmuni. I wanted to sleep in her room. I wanted my mother to return “our” chopsticks when she used them in the kitchen. The edges of my mind seem to prickle with recognition. A white linoleum floor, my hand on Halmuni’s knee as I demand my mother leave us alone.

I live in Brooklyn now, and Halmuni lives 6,853 miles away. We text in Korean, and she sends me selfies. A recent one: she wears sunglasses and a camel coat, impeccable orange-red lipstick. The picture is, ostensibly, to show me that she loves the scarf I sent her, but I think she is also lonely. She has been divorced for many years, her friends are dying (as she often reminds me), and though she has five daughters, seven grandchildren, and one great-granddaughter, we are all busy with our own lives. As we text, Halmuni tells me about walking her dog around the neighborhood fields, and I tell her what I am writing these days.

She always begins with, “Have you eaten?”

She always ends with the same reminder, “Eat well.”

“Don’t forget to eat, eat, eat.”

Although her daughters provide for her, though she has pocket money to dine at restaurants if she desires, food is a central figure in her life. Hunger is a memory she cannot escape.

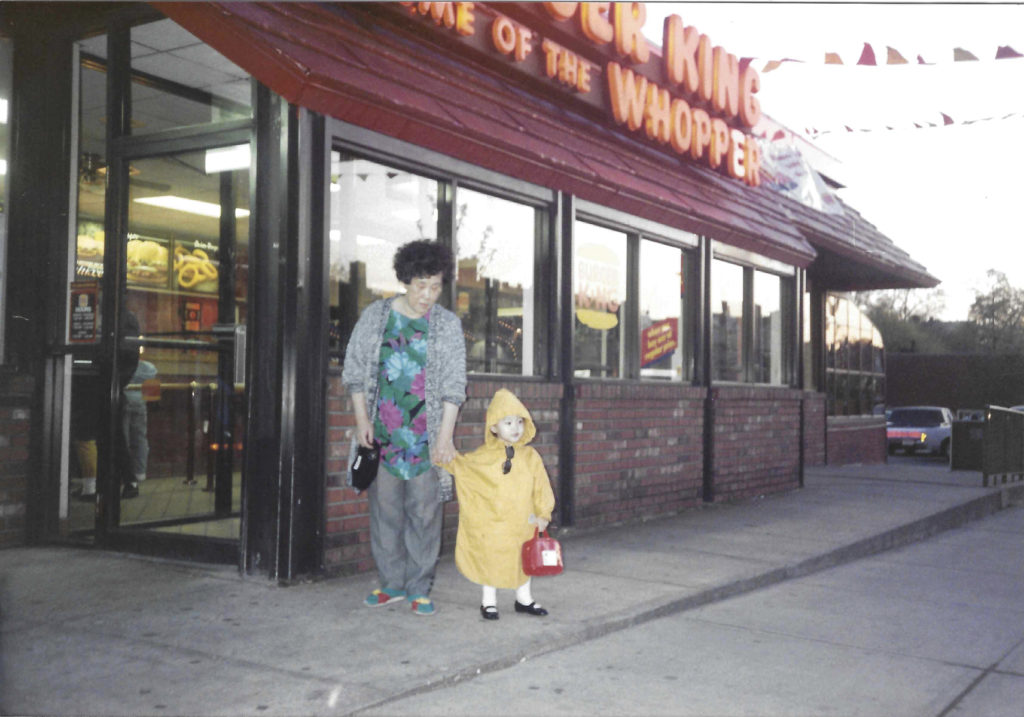

In another photograph of us, we stand outside Burger King holding hands. I wear a too-big yellow rain jacket and clutch a squishy-looking red lunch box. My grandmother looks tired in a gray cardigan and a gaudy, flowered shirt. She does not speak English, she has left everyone she knows in Korea, and she must now take care of a small, well-fed child every day. She is only fifty-four years old.

When she speaks of that time together, those years when she shelved her life to take care of me, it is only with fondness. She acts out scenes of my four-year-old-self, how I would copy her, my hands on my hips, yelling “No English! No English!” to passersby who got too close. She mimics me mimicking her, layering our past selves into a thick weave. But I don’t remember, and so I imagine. I consider the parts my grandmother has forgotten or now hides away. The loneliness, the strange food, and most of all, the plenty. America and her wastefulness.

On one recent evening, I walk over to my friend’s apartment for dinner. As she prepares pasta and I uncork a bottle of red wine, we speak about memory. I do not understand how memory works, I say, how we think we remember things that never happened and how we can forget the things that have. I want to know what I would find if I unspooled my memories and laid them out against my mother’s and my grandmother’s. I imagine the textures and seams of our competing recollections; I imagine them synthesizing to form a richer whole.

My friend grates cheese and tells me scientists are studying how organisms genetically transmit information from one generation to the next. For example, she says, during metamorphosis, caterpillars dissolve all their tissues in their cocoon. They become, essentially, liquefied mush. That mush then reforms itself, cell by cell, into a new organism. And yet, when scientists condition caterpillars to fear a specific smell, the act of metamorphosis does not erase that memory. The new organism that emerges, the moth, will still fear the scent that haunted their caterpillar forms. I imagine all that Halmuni must shrink from, the scents she has endured in her life. I wonder if there are smells I fear without knowing why, if her memories have worked their way into me.

My grandmother was fourteen when the Korean War began. She and her mother, like millions of others living in both halves of Korea, fled to Busan. Bewildered at the sudden onset of war, civilians streamed south. Their belongings were hoisted onto a-frame carriers and bundled into blankets. They were refugees in their own country. Halmuni tells me of the dead bodies on the roadsides, their particular, indescribable, multi-layered stench. When I flinch, she shifts to blander details. She recalls packing squash gourds, a blanket, a pot of beans and rice.

“What did you do when the food ran out?” I ask.

“We’d eat anything we could find,” she says. “We peeled the bark from trees, collected the sap, and cooked that. We picked potato vines, roots.”

“How did you know what was safe to eat?”

“I grew up watching birds, seeing what they ate, what made them die and what let them live.” She clucks. “When you grow up in the country, you know what’s edible like you know your own bones.”

I nod, but I don’t know my own bones. I don’t even know what it would mean.

She tells me of straw shoes chafing her ankles on the long walk south; of begging for food throughout Busan, hiding when an army tank rolled through, frightened by their mechanized roars; of staring at a white man’s face and wondering where all the color had gone. What shape do these memories hold in comparison to later, steadier memories? I imagine the weight of her trauma in my palm, opaque and heavy. How much has been willfully or subconsciously forgotten?

*

In college, I take my first creative writing workshop. I like to write, but I don’t know anything about writing as a literary act. Instead, I type out fragmented scenes about young college-aged women. My stories meander, follow the lines of slight traumas. My own small violences, exposed through invented characters. In one-on-one conference, my teacher tells me to write about ‘what I know.’

“But I don’t know anything,” I say. I am nineteen. I am eager to begin life, which I believe will soon start, perhaps after college.

“Write about who you are,” my teacher says.

‘What I know’ and ‘who you are,’ I realize, are code for my Koreanness. I resent this teacher. I am more than what I look like. I write to figure out what I don’t know, I think. I ignore this teacher’s advice and continue submitting stories about faceless, raceless, colorless young women in shitty relationships.

When I turn twenty-four, a first-year graduate in an MFA program, I decide to start a novel. I finally feel like an adult, like I am living life, but I am also beginning to understand that who I am does not end with my body, my bones. My parents and sister. Halmuni. My almost-estranged, dementia-ridden grandfather. My father’s parents too, who have passed away. My aunts and uncles. I want to understand who they are, what they have lived through.

I visit my family in Korea between my second and third year of the MFA. Summer in Seoul is full of thick heat that clings to your neck, the back of your knees. I ride a train from Seoul to Hoengseong, and I remember the buses we took when I was younger, the roiling in my stomach and inevitable retching from the bumpy seats and too-fast turns.

In Halmuni’s apartment decorated with succulents, crosses, family photographs in colorful frames, figurines of children in hanboks, and pink porcelain angels, she tells us her history. My mother and I sit cross-legged on the wooden floor. We chew on dried squid legs and listen. Even my mother doesn’t know this full history. The war was not the end of the difficulty; for many years after, with daughter after daughter, Halmuni strove to survive. She had no time to sift through the past, to share memories with her children.

Halmuni is eager to share, in the way the elderly are as they face certain, impending demise. “By the time I was your age, I had five kids,” she says to me.

I am twenty-six; I am in graduate school, writing and teaching, dating a man who will one day become my husband, spending too much on rent and drinks. I cannot imagine another person growing inside me, passed from my body to the world.

In a study conducted at Emory, scientists find that fear can be inherited through generations of mice. These scientists conditioned mice to fear the smell of cherry blossoms, and when the mice had children, the offspring, though not conditioned, feared the smell as well. Even a generation later, the offspring’s offspring exhibited the same fears.

I know that faint, floral scent. Cherry blossoms remind me of Japan, of my grandmother’s childhood. The name given to her at birth, Park Soonnam, erased. Matsuda Fuuna emerging in its place.

My grandmother lived under Japanese colonial rule until she was nine. Korea, still united and whole, was colonized in 1910. During this period of forced occupation, Japanese teachers taught Korean students how to view the world through their imperialist language, their history, their foreign tongue.

“Which was worse? The colonialization or the war?” I bite into another squid leg. “Do you remember?”

She remembers, but she doesn’t know. She thinks of the end of World War II, Korea’s Independence Day a month later, when Japanese rule ended but the Soviet and United States occupation split the country in two.

“At least we felt a little free for a while,” Halmuni says.

We eat kongnamul guk the next day. As I slurp up broth and soybeans and radishes, Halmuni heaps sweet potato stems and seasoned spinach onto my rice bowl.

“Eat more,” she says.

I have heard this phrase all summer long and my stomach feels perpetually enlarged. I am too full, again, and nearing irritation. “I can pick my own banchan,” I say.

She clucks, “You’re too thin,” but she retreats to her soup, her spoon wavering in the air.

I touch her hand immediately. I say the food is delicious. I ask her for more, though I am bursting.

So much changed during my grandmother’s lifetime. From colonial rule to civil war to dictatorship after dictatorship to now, the first presidential impeachment. From a young girl who stood in a government line in Busan, barefoot in the snow, to a woman who can communicate with her grandchild halfway across the world through a device that fits in the palm of her hand.

I think of Halmuni heaping vegetable stems and leaves on my bowl, how she always wants to feed. How she rejoices in sharing a bowl of patbingsoo with me on a warm summer day. How she always tells the same story, of how I used to call it soo-bing, mixing the syllables, when I was young. There is a joy in being able to bring your child’s child a meal she does not need, as delicious and sweet as shaved ice.

When she texts me, “My darling Hana, how are you? I’m worried you and Eric are not eating well.” I do not tell her what I have learned from the scientists about memory, history, blood. I reply with, “We are fine!” I send her a picture from a few days before. “It’s snowing here. Have you been celebrating the impeachment?” I expect her to send me something cheerful back. Instead, she responds with, “You both look like you lost weight. What are you eating?”

“I made miyeokguk for our birthdays,” I respond.

“Then why do you look so thin?”

I reassure her as best as I can. I describe for her all the other meals we have been eating lately. Lamb shanks. Pajun. Kimchi jjigae. Burgers. I scroll through my phone to see if I have a photo to send her as proof of our healthy appetites, our plentiful lives. When she is satisfied, sure that we are well, she tells me to take care of myself. To remember, always, to eat. And I realize again: I am more than my body, my bones.

Crystal Hana Kim is the author of If You leave Me, out this week from Harper Collins

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2mZt10U

Comments

Post a Comment