As a teenager my view of the world was bleak. I was the only one of my small group of misfit friends to leave home to go away to college. Not long before I did, I saw Agnès Varda’s film, Vagabond. I can’t remember if I saw it at the local art house cinema (which went out of business the same year), or if I pulled it off the rack at the neighborhood video rental store, or if I happened upon it on Cinemax, which in the late 1980s was known for showing the HBO leftovers: foreign films and soft porn. I’m fairly certain I saw Vagabond alone.

There were few female heroines that made sense to me growing up in the 1980s, an era whose filmic representations were overwhelmed by John Hughes and his bubblegum suburbia, where misunderstood girls were eventually sexualized, and therefore welcomed to the ranks of fitting in. That kind of conformist resolution was unsettling to me. Agnès Varda finally gave me a female protagonist who didn’t compromise.

Vagabond interweaves its story in a hybrid documentary style. It opens with a young woman named Mona dead in a ditch. The police investigate the scene, take pictures, and wrap her up in plastic as if she is being put out with the trash. Varda offers a short voiceover: “No one claimed the body…I know little about her myself but it seems to me she came from the sea.” Varda then fades into the role of a silent off-screen filmmaker interviewing the people who encountered Mona in the weeks leading up to her death. With the exception of Mona (Sandrine Bonnaire) and a few other key roles, most of the characters are played by non-professionals, locals from the area. They speak directly to the camera, recalling how they met Mona. To them she is, alternately, a blank slate, a whore, a romantic, a symbol of freedom, a nuisance, a protégé, or easy pickings.

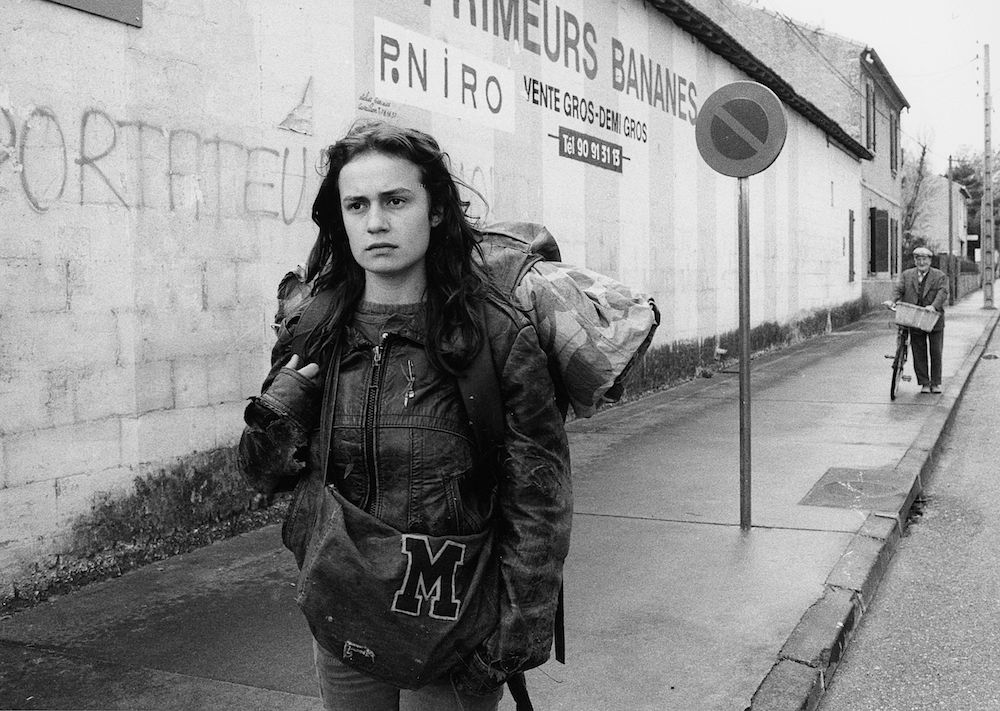

But when I first watched Mona as a teenager, she captivated me, her unapologetic independence a beacon of what I yearned for. In the scenes that follow these initial interviews, Mona, still alive, drifts through wintery southern France, her stringy unwashed hair constantly blowing in her face. She has a backpack, a tent, cigarettes, and hardly any money. She gives no reason for her lifestyle and no backstory: she would prefer to say nothing at all. A rage simmers deep within her—she stomps across empty farm fields, the tracking shots unable to keep up—but for the most part she doesn’t give a shit.

Throughout the film we aren’t given many clues as to why Mona has chosen life on the road, though we are given some: she didn’t like school and didn’t like her job. She isn’t living “without roof nor law” (the translation of the original French title of the film, Sans Toit ni Loi) for any political cause, but Mona, nevertheless, does not accept her place in the power structure of the world. She chooses to live outside of anything that might confine her and therefore lives literally outside—on a cold beach, within an empty construction site, in a wintered-over garden. She has desires—food, sex, transportation, alcohol, weed—and she satisfies them by stealing, fucking, and hitching. Upon meeting someone new, she never asks for anything, never apologizes, and never says thank you. She demands, she takes what she wants, and she walks away.

But beyond Vagabond’s quiet defiance, it is also the fact that its protagonist is a woman that makes the film so startling. We’ve seen male drifters and loners throughout film history. A man alone has a reason, and his isolation is therefore noble: in Manchester by the Sea, Casey Affleck’s character exiles himself as punishment for the accidental death of his children; in Ironweed, Jack Nicholson leaves home after dropping his infant son; Harry Dean Stanton in Paris, Texas follows an amnesiac path trying to reunite his son with his mother, whose relationship he destroyed through abuse and neglect.

A male drifter is doing penance for something for which he was found innocent, but for which he cannot forgive himself. A woman alone is crazy. That she is not a sex worker makes her crazier. She has no purpose and is serving no one’s needs. Something must have happened to her (as in Wendy and Lucy), or she must be the victim of something (Wanda), or she must be on a prescriptive journey of self-discovery with a discernible end and a scheduled return (Wild; Eat, Pray, Love).

Mona will have none of it. She has sex with a mechanic who lets her camp in his yard, then makes fun of him. She flips off a truck driver who kicks her out for not sleeping with him. She abandons her lover when he runs out of weed and is beaten up by thieves. If someone tries to help her by giving her money, she laughs at their instinct for charity. “I live outside,” she says.

To watch Mona is like examining your own guts. She reveals all the revolting stuff that humans do: eat, fuck, shit. Mona blows her nose into her hand and flicks the snot away. She eats sardines out of a can with her fingers and gnaws on stale baguettes. She never washes her clothes. Warnings of death don’t seem to bother her. According to an agronomist who gives her a ride, all the trees are doomed from an invasive fungus; the loneliness of the road will eventually kill you, says a hippie farmer who tries to help her.

Mona’s downfall is swift, predictable, and ugly. She becomes increasingly fucked up on alcohol and drugs, and falls in with a guy who seems intent on eventually pimping her out. She attaches herself to a group of junkies so she can use their stash, but they, in turn, use her to panhandle. She becomes part of their daily routine, and in doing so, loses her autonomy. She runs out of a squat that has caught fire, her only remaining possession a ratty blanket. She begins to look more like someone without a home and less like someone making an intentional alternative life. When she stops in a flimsy plastic greenhouse for shelter, she shivers from the cold and suddenly looks fearful and much younger than before, or perhaps she looks her real age, the same age I was when I first saw the movie. Mona, who says, “I don’t care, I move,” loses the ability to control her movements. She flails about, knocking into commuters at a train station. She vomits on the floor.

We know from the opening scenes that Mona winds up dead in a ditch, but I felt an adolescent-like anger rekindled in me as the film neared its end. It is unfair that she dies, that she loses. Something in me thinks that if I were Mona, I could’ve done it better. I could’ve made it work. But how? By compromising? By staying with the goat farmers through winter? By stealing another traveler’s gear? The brilliantly frustrating thing about Varda’s film is that it doesn’t judge Mona. What happens to her isn’t necessarily inevitable, but it was always possible.

Varda offers no final word and she doesn’t wrap things up for you. She merely delivers you to where she began, which is where you knew the film would end. It feels eerily like you are the last person to be interviewed for this faux documentary. You are a witness to this fiction that has been structured like a truth. It all feels like it has happened in real time. But Mona doesn’t care if you watch or not. I am not here for you to figure out, I imagine her saying, because, like me, she says so very little. Try to judge me, she says, flipping off the camera. Try to pin me down, she says to her audience. I terrify you, don’t I?

Andrea Kleine’s second novel, Eden, will be published in July by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2uh8w2J

Comments

Post a Comment