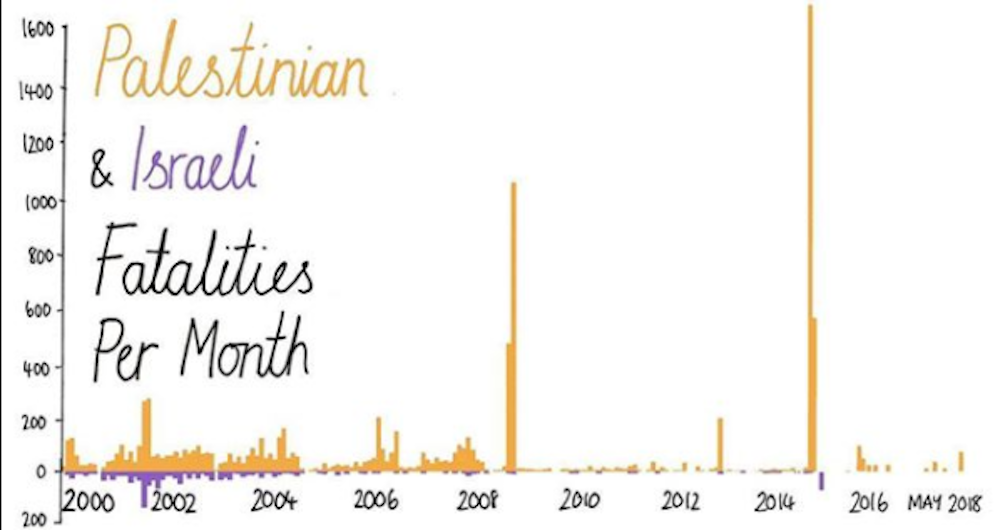

Mona Chalabi is the Data Editor for the Guardian US. Her beautiful Instagram account is a mixture of data, visual art—and taken together—a kind of self-portrait in infographics, illustrating Chalabi’s preoccupations, curiosity, neuroses, politics and sense of humor. You’ll find a chart on the “Probability of a White Christmas” (at least one inch of snow) from Michigan to South Carolina, and another of an outstretched leg, illustrating the downward slope in Pantyhose Sales in Japan. The caffeine content of various beverages is represented by stretched-open bloodshot eyeballs. Another chart, of penises, represents the “Average Time to Ejaculate During Vaginal Penetration”—“Median = 5.4 minutes,” though her caption notes, “This data comes from 500 heterosexual men in monogamous relationships for at least 6 months. So, not exactly representative. The data was collected by asking them to use a stopwatch, which you’d think would kill the mood at least a bit. But still, interesting, no? Yes. Also interesting: the spike in people Googling “Will I Die Alone?” around Valentine’s Day, and the number of Decapitated Animals Found in New York Parks, (with chickens and pigeons in the lead, ahead of goats and cats), the degree to which Trump campaign contributors profit from his policy of detaining immigrants, and the current disparity in earnings between black and white Americans. Some aren’t charts at all, just facts and drawings, like the one of two hands being pulled apart—one big, one small—posted alongside the fact that 1,995 children were separated from 1,940 adults at the US-Mexican border between April 19th and May 31st of this year. Some artists are perfectly suited to the visual medium of Instagram. Others provide you with information that may broaden your perspective, or at least redeem your procrastination. If these two types are in a venn diagram, with varying amounts of overlap, then Mona Chalabi is a total eclipse. —Brent Katz

In times of chaos, it’s often the little things that have the biggest impact. The details of our lives—fleeting impressions, splintered memories, irreparable fragments of identity—eventually accumulate to form our unique perception of the world. Akil Kumarasamy’s multifaceted debut collection, Half Gods, pays tribute to these little things that haunt each generation of the Padmanathan family through their journey from civil war-torn Sri Lanka to the quiet “wilderness of Jersey.” Shifting perspectives from an Angolan butcher, to a single mother living with her aging father, to a pair of brothers on a trip to Lake George, and beyond, Half Gods culminates in a kaleidoscopic and nuanced narrative. Kumarasamy’s ability to wrinkle time and space like paper is just one reason that the interwoven tales of each family member flow so seamlessly, while still maintaining their individuality. In a style reminiscent of Arundhati Roy’s dreamy (yet unflinching) detail, Kumarasamy gives her readers a rare opportunity to reflect upon the instances responsible for the formation of identity on both a personal and a national scale. —Madeline Day

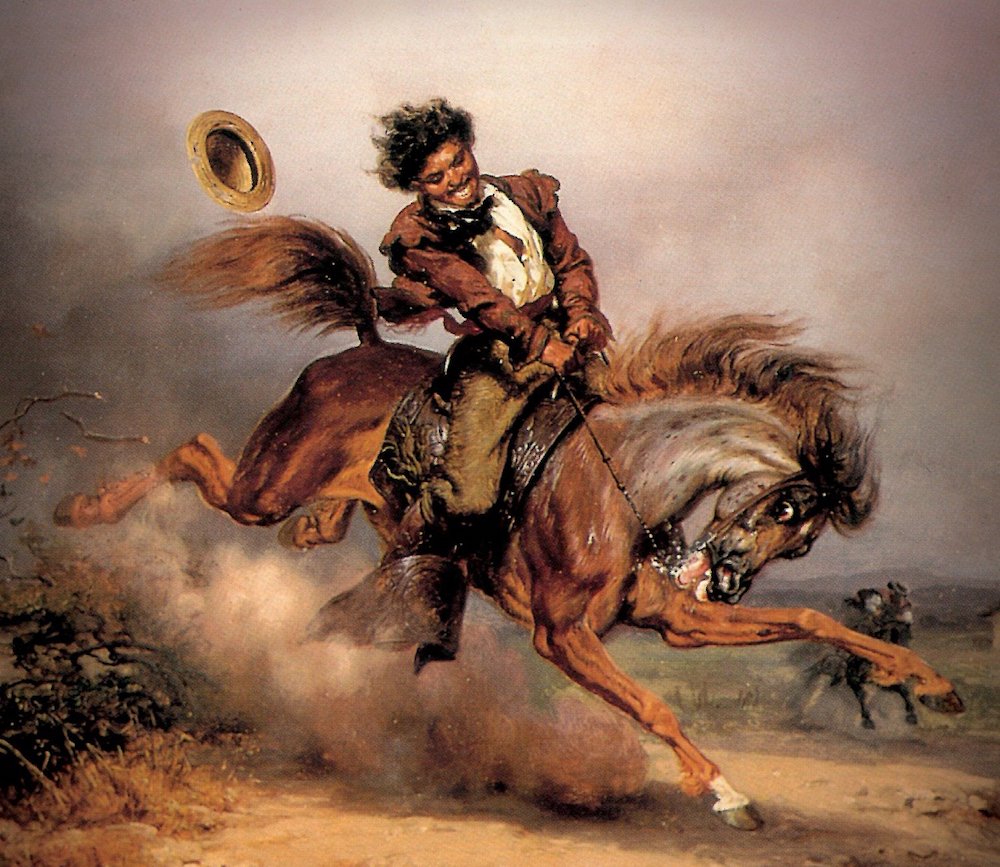

I grew up an hour’s drive from Cantua Creek, the place where Joaquin Murrieta, also known as the Robin Hood of El Dorado, was said to be killed by state rangers in 1853. After Murrieta was attacked by jealous white miners, beaten, forced to watch them rape his wife, and driven from his claim, Murrieta, and one of his infamous partners, Three-Finger Jack, lead a gang of bandits on a revenge-fueled campaign up and down the newly formed Golden State. I didn’t know much else about the legend, which is why I devoured the new reprint of John Rollin Ridge’s 1954 novel, The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta: The Celebrated California Bandit—which I only now learned was the first novel published in California, the first novel published by a Native American, and the first American novel to feature a Mexican protagonist. Joaquín Murieta is a fascinating story, one that is as much a foundational narrative of the state of California as it is about American racism and state-sanctioned violence—when a severed head, said to be Murrieta’s, was preserved in alcohol as proof that he had been slain, government officials had it displayed across the state as a warning. What’s better, although for narrative sake not included on Ridge’s book, is that for years after Murrieta’s family and friends reportedly said that the head was not Murrieta’s, and that he was still alive. Today, on California Historical Landmark #344 (a plaque commemorating where the posse of state rangers killed Murrieta) graffiti reading “LIES – LIES – LIES” is painted around the monument’s base. —Jeffery Gleaves

This week, I went to the Brooklyn Museum. Yes, I was there for the David Bowie exhibition, but found myself captivated by the much quieter resonance of Cecilia Vicuña’s show Disappeared Quipu. A quipu is a record-keeping device used by the ancient people of the Andes to keep records—without a written language, they used knotted thread to keep track of both practical day-to-day matters and their own narrative history and lore. However, that is the extent of modern Western understanding of the quipu—precisely how or what they communicated is lost. If you subscribe, as I do, to the belief that language is inextricable from the construction of reality, the inaccessibility of a disappeared language will shake the steadfastness of connection you feel to the world around you. Vicuña’s installation consists of enormous swaths of fabric hanging from the ceiling, some hanging straight and some knotted, through which low, indistinguishable vocals are piped. The effect of pairing quipus with the sound of the human voice left me saturated with the tragedy of having the key to a culture, but no lock in which to turn it. —Lauren Kane

Throughout her incredible Netflix special, Nanette, Hannah Gadsby reminds us that she’s quitting comedy. At first, this seems like a bit. After all, she delivers the line while standing onstage at the packed Sydney Opera House; this is roughly the equivalent of a NASCAR driver clinching the cup as they poke their head out the window and scream about the impending obsolescence of automobiles. But Gadsby is getting at something deeper here. Her aim is to dismantle standup as a genre and reckon with its unscrewed pieces. As in a fugue, she introduces each element of her routine carefully, then pulls it back, only to return to the same element five minutes later. She revisits some of her past material—most notably a joke about almost getting beaten up by a man who assumed she was flirting with his girlfriend. Lured along by Gadsby’s natural gift as an orator, we don’t see what she’s actually doing: stacking these elements like plates behind our heads, with a hammer raised above it all. And when that hammer falls, it’s devastating. Comedy is powerful, Gadsby argues, but it also masks and enhances trauma—especially for marginalized performers. This is comedy meant to scorch, a sort of ars poetica of standup that could exist only in 2018. —Brian Ransom

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2lVk3RA

Comments

Post a Comment