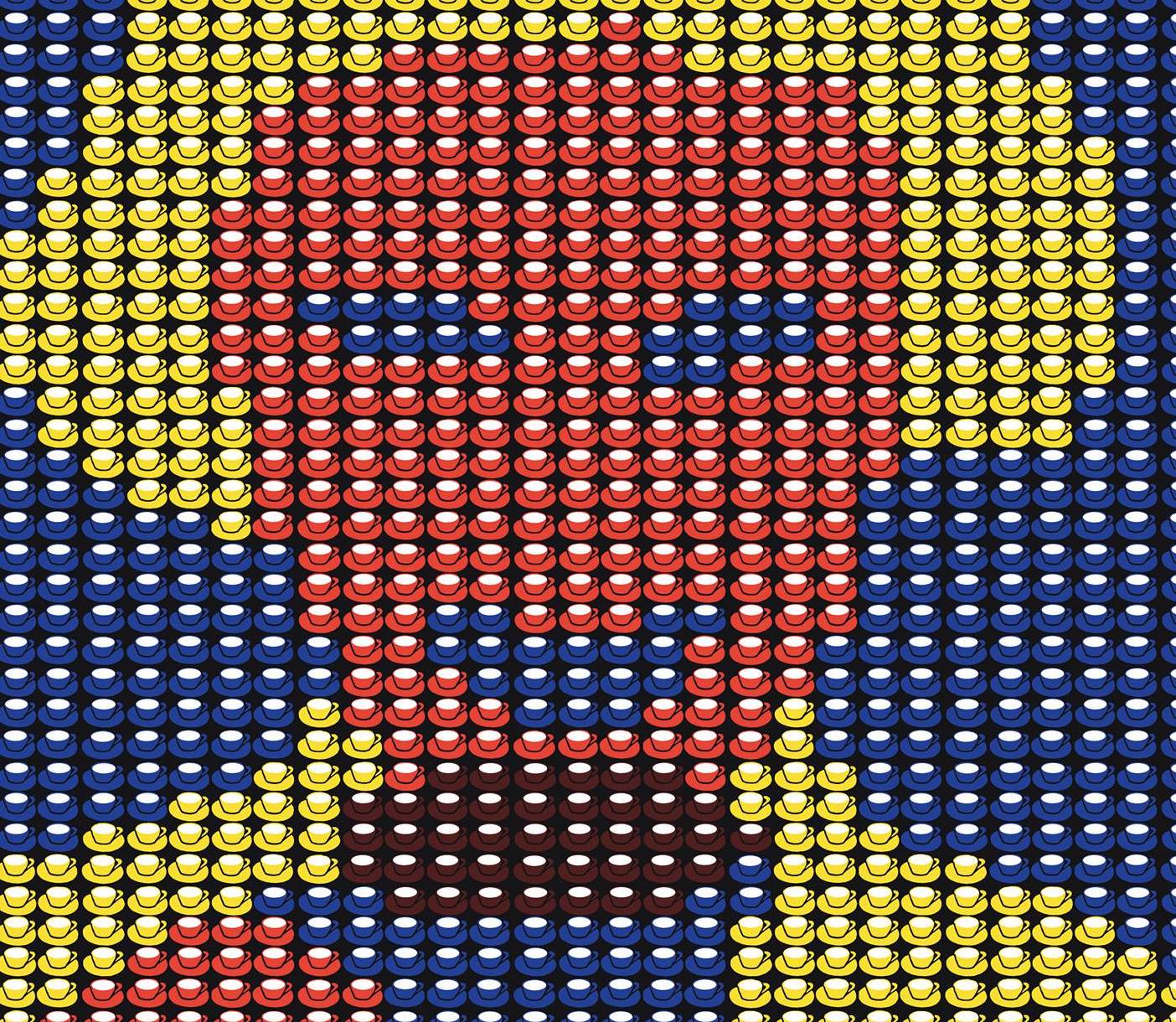

The devil truly is in the details when it comes to Thomas Bayrle, whose first New York solo survey, “Playtime,” opened in June at the New Museum. His paintings are hypnotic. Large images are made up of tinier and tinier versions of the same image, demonstrating a Pointillism all his own. The first floor of the survey is saturated with color and pattern (even on the walls and floors), an initially delightful effect that quickly becomes creepily unreal. My companion and I sat transfixed, eyes wide and mouths slightly agape, in a theater where the screen played the image of a digitally rendered face, zooming in to reveal that the likeness was in fact comprised of thousands of screaming mouths, and then zooming back out again. Face after face appeared on the screen, each revealing itself as a honeycomb of horror. Not all of Bayrle’s work is so overtly dark—a lot of it presents itself as playful, as the exhibit’s name suggests. The motif of the Laughing Cow logo is plastered everywhere, but even that eventually becomes warped, the way a word does when you’ve read it too many times. Bayrle demonstrates foresight in his concepts, but also in his technique, using computers to do work long before such methods were taught in art schools the world over. The second floor shows his more recent work, much larger in scale, bereft of color, and focused on the humming spiritual nature of modern engineering and technology. The repetition of windshield wipers or pistons are presented as devotional, and as we watched, again transfixed, the arms of a mechanical deity moved to a looping measure from Liszt. —Lauren Kane

With the props of a name and gender conspicuously missing, the narrator of Christopher Stoddard’s At Night Only must search elsewhere for an identity. A passel of self-effacing substitutes offers itself up, comprised of drugs, sex, and substance-induced paranoid visions. The dissolution of two relationships—between the narrator and Pedro, a glamorous underground art world celebrity, and then between the narrator and Jacques, a narcissistic emerging actor—give the novel its arc. Pedro’s half of the novel seems more literary than Jacques’; there’s a brilliant passage revisiting the narrator’s “Goth teenage years,” during which he lit black candles and whispered Wiccan, moving among shadowy individuals whose presence make the narrator claustrophobic. But the second half’s less flashy prose style is exactly what the narrative calls for. As the narrator edges toward accepting that no one will be their savior, they stop making mythologies out of harmful relationships. This is Stoddard’s Story of the ‘I’—which, not by coincidence, he often casually drops from his sentences (“Rinse off. Get up. Get out of the tub.”). Though dubbed a ‘tragedy’ on the jacket, At Night Only looks unrelentingly for a way out of fake love, fake relationships, and fake identities. —Ben Shields

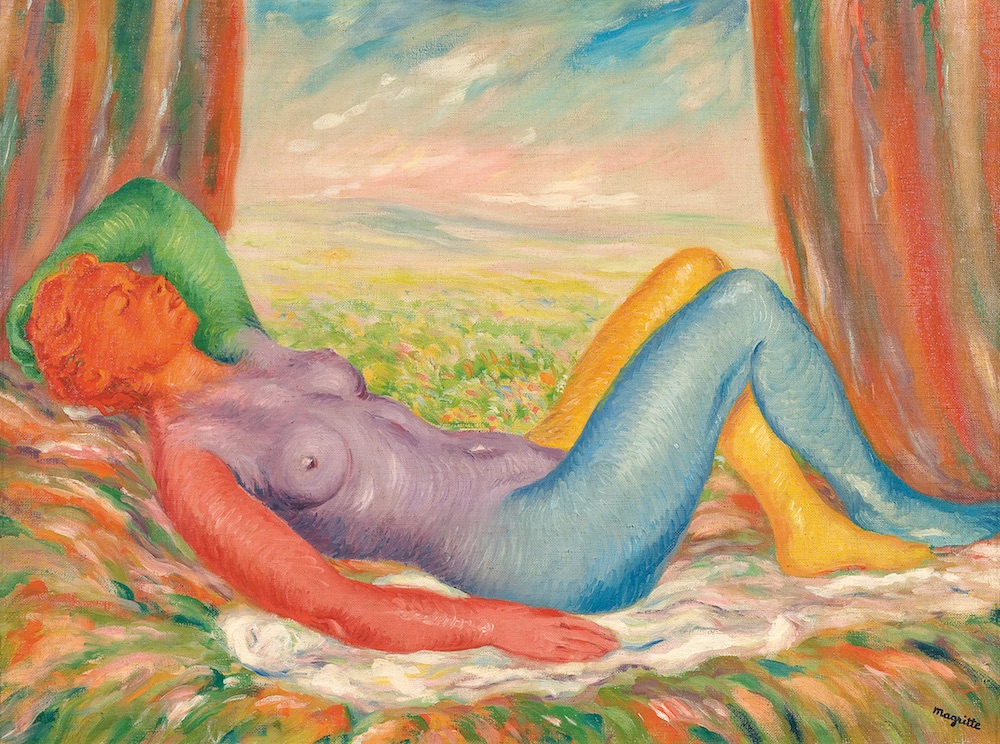

In May 1948, René Magritte decided at last to put “ses pieds dans la plat”— his foot in it. Magritte’s first solo exhibition in Paris featured just under thirty oil and gouache works from what has come to be known as his off-color Période Vache, a spasmodic break from decades of what he called his “tactical conformism.” Vache in French translates literally to “cow,” but art critic Bernard Marcadé unfolds the unceremonious meaning of the word in the context of Magritte’s work. For instance, “an unpleasant person is described as a peau de vache (cow-skin),” and “amour vache (cow-love) refers to a relationship [that is] more physical than emotional.” The casually bizarre and crudely fetishistic paintings of the Période Vache prove this slang to be fitting for Magritte’s ultimate goal: to offend, to outrage. Magritte approaches Surrealism scatalogically; the hyperrealist style that brought him fame in the 1930’s is swallowed by the bold brush strokes and outlandish color of pieces like La Famine and The Pictorial Content. Similarly, Magritte’s rendition of Édouard Manet’s Lola de Valence is a cartoonish parody, literally undressing Manet’s Realist portrait and replacing it with a fleshy pink caricature. Of course, Magritte’s 1948 exhibition failed spectacularly—not a single piece was sold. Yet Magritte succeeded in breeding discomfort amongst his Parisian audience, invoking a sense of disruption and confusion that he believed to be essential to his own brand of Surrealism. To experience Magritte’s work firsthand, contemporary viewers can visit the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, whose exhibit “The Fifth Season” is on until October 28, 2018. —Madeline Day

Henri Michaux, the wonderful and wonderfully strange mid-century Belgian painter, writer, poet, traveler, etc. did not find drugs recreational. As he informs us at the close of his 1956 magnum opus of mescaline experience Miserable Miracle (excerpted in The Paris Review no. 15): “I regret to say that I am more of the water-drinking type. Never alcohol. No excitants, and for years no coffee, tobacco, or tea. From time to time wine, a little.” In the foreword he states succinctly of mescaline itself: “Should I speak of pleasure? It was unpleasant.” He does not believe, as his compatriot in mescaline self-experimentation Aldous Huxley seemed to, that drugs are capable of imparting philosophical wisdom or inducing enlightenment. At most, Michaux concludes, drugs are “an opening…only a step.” The impulse beneath Michaux’s mescaline experiments seems to have been literary, driven by a sense of fresh woods untouched by other prose styles. In Miserable Miracle, Michaux attempts, like an attentive explorer, to deduce the workings of this strange place, the convulsing ball of snakes that his mind has become. We witness Michaux organically arriving at a Finnegan’s Wake-esque internal logic and prosody— “And here it is again just as it was before, with more stories than you can count, with a thousand rows of spasmodic bricks, a trembling, oscillating ruin, crammed, stuttering Bourouboudour.” Michaux may not have returned any wiser from his trip, but he did bring news, and strange new textures. —Matt Levin

The Los Angeles rapper 03 Greedo belongs to a class of artists who, out of sheer prolificacy and genius, create their own vortices. Like the outputs of Gucci Mane and Chief Keef, Greedo’s music rewards obsession and demands immersion. This is my favorite type of rapper, and over the past month, I’ve been absolutely hooked on Greedo, bouncing from his Purple Summer mixtapes to his collaborations with Drakeo the Ruler, eventually landing on his latest project, God Level, which promises to launch his career, just as he begins a twenty-year prison sentence. I remember when the music of another vortex-creating rapper, Lil B, first clicked for me. On “1 Time,” one of the final tracks of Lil B’s weirdo masterpiece Angels Exodus, he raps, “I already think I’ma die from the way I’m living / I’m by myself eating fast food on Thanksgiving.” These lines, nestled on the back half of an album that includes a joyous ode to the horror video game Resident Evil, hit like a brick. Greedo has a similar tendency for vacillating moods. He lets you float—his melodies are impeccable, his flows infectious, his beats drenched in the slap and squish of West Coast hip-hop—until he tugs the rope and drops a counterweight, plunging you back into the icy waters of his trauma. On “Jealous,” a paranoid lo-fi banger, he slips in these lines: “Tell me have you ever slept in the park / Fuckin’ cheesy, you just sleep in the car.” What a gift it is to be let into the kingdom of Greedo’s mind. And though he’s earned comparisons to everyone from Max B to Boosie Badazz, and though I’ve spent half of this staff pick placing him in the context of other rappers, Greedo’s style and voice are urgent and wholly his own. —Brian Ransom

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2myQu8Q

Comments

Post a Comment