Inside an old brick building in Somerville’s Davis Square, below the gilded stage and the red velvet seats, there is an unusual museum. Hidden in the basement of the 1914 Art Deco building is a collection of hideous paintings and disturbing drawings otherwise known as the Museum of Bad Art.

“You wont ever see this stuff in the Museum of Fine Arts,” says curator Michael Frank. Frank is the kind of guy who can’t pass a yard sale or a flea market without stopping to browse. He loves ugly things, but for him, ugly is a problematic word. “When I read your email, I thought ‘uh oh,’” he admits. “Calling something ugly is like calling something beautiful. The minute you say it you’re in a difficult spot, trying to define what that really means.”

Frank prefers to think of these paintings as “badart,” one word, no hyphen. Badart is not the inverse of “good art,” it’s the inverse of “important art.” Some might call these pieces “outsider art” and in the past, many of them could have been termed “primitive” or “art brut.” I prefer to think of them as ugly. Charming—like the dancing dog wearing a tutu or 90’s eyebrows on one particularly serene Virgin Mary—but ugly nonetheless.

However, I understand where Frank is coming from. For Frank, ugly is a word that suffocates, depriving his favorite paintings of their rightful, playful air. Ugly is also a word that carries hard moral implications; for centuries, ugliness has been associated not only with sickness and deformity, but also dishonesty, violence, aggression, and bigotry. Consider the term “ugly American” or the repeated critique of Trump’s “ugly” acts. The word itself comes from the equally discordant sounding ugga and uggligr, two Old Norse adjectives that meant “dreadful, fearful, aggressive” (other words that bloomed from the dreadful root include loath and loathsome). The meaning only changed in the 14th century, when “uglike” stopped meaning terrifying and began to mean “unpleasant to look at.”

Even though the word ugly is now primarily used to describe the unaesthetic aspect of things rather than their deep moral fiber, it retains elements of its original meaning. Using it can shift a well-meaning aesthetic critique into the realm of moral judgment. This is unfortunate for those of us who genuinely enjoy, and celebrate, ugly things.

If you, too, want to appreciate ugliness, the first thing you have to do is stop assuming that it is the inverse of beauty. We tend to talk about aesthetics as though the categories are locked in a battle, good versus evil, light versus dark. But opposites are a crutch. Beauty and ugliness do not negate each other.

Science supports this idea. Studies done in the emerging field of neuroesthetics (studying how the brain responds to aestheti stimuli) have found that beautiful paintings and ugly paintings light up the same regions of the brain: the orbitofrontal, prefrontal, and motor regions of the cortex. Oddly enough, the pictures ranked most beautiful activated the orbitofrontal region most and the motor region least, whereas the pictures ranked ugliest activated the orbitofrontal region least and the motor region most. The author of this particularly study, Semir Zeki, tentatively suggests that perhaps ugly things mobilize the motor system so that we can flee from the unwanted stimuli. The same study has lead Eric Kandel, author of The Age of Insight, to argue, “Beauty does not occupy a different area of the brain than ugliness. Both are part of a continuum representing the values the brain attributes to them.” Although we experience them differently, beauty and ugliness both tap into our emotional center, an area deeply involved in analyzing other’s motives and actions and generating both sympathy and empathy. Kandel writes:

Our response to art stems from an irrepressible urge to recreate in our own brains the creative process—cognitive, emotional, and empathic—through which the artist produced the work. This creative urge of the artist and of the beholder presumably explains why essentially every group of human beings in every age and in every place throughout the world has created images, despite the fact that art is not a physical necessity for survival. Art is an inherently pleasurable and instructive attempt by the artist and the beholder to communicate and share with each other the creative process that characterizes every human brain—a process that leads to an Aha! moment, the sudden recognition that we have seen into another person’s mind, and that allows us to see the truth underlying both the beauty and the ugliness depicted by the artist.

Art, both badart and Important Art, can reveal the inner workings of the artists mind. Beautiful art is at its best and most useful when it illuminate truths about the human condition, but badart can reveal the inner workings of one individual’s mind—their strange lusts, their disturbing daydreams, their anti-social desires, and their nonsensical fears. Beautiful art can speak to the general trials and triumphs of being human, but badart can speak equally eloquently to the highly specific neuroses and joys of one singular mad mind. After all, we all like sunsets. But there’s a unique appeal to the Museum of Bad Art’s behemoth crimson cat devouring a pale-faced human under a Pepto-Bismol pink sky.

Ugliness has never been the subject of much scrutiny. For the most part, artists and thinkers have treated ugliness as an immutable category, filled with things they simply didn’t like. These included dangerous landscapes, differently abled people, and objects that showed signs of too much use. When survival was a number one priority, people viewed anything potentially threatening as ugly. And for the most part, ugly works, particularly pieces that were unintentionally ugly, were forgotten to history.

As a result, the most significant ugly works created before the 19th century were intentionally ugly, created by technically skilled painters who decided, for whatever reason, to depict an ugly subject. Often, ugly art was created as a warning. There but for the grace of god go I, screams the gargoyle clinging to a medieval façade. To contemporary eyes, the art of the dark ages looks ugly as a whole (consider this great Vox explainer about ugly babies in medieval paintings.) At the time, however, people didn’t consider the malformed dogs or awkward hat-wearing crows to be ugly, though they did know that “doom paintings,” which depicted the worst-case afterlife scenarios, were hideous. Doom paintings highlighted the difference between heaven and hell in order to strike fear into the heart of viewers and thus discourage them from, say, coveting their neighbors hot wife or lying when the taxman came around to collect coins. Sometimes these paintings functioned like the medieval version of Jonathan Edward’s hellfire and brimstone sermons; they actually made the afterlife look interesting, stimulating, and perhaps even a little bit appealing.

Painted in the late 15th century, Hieronymus Bosch’s “Garden of Earthly Delights” took from the tradition of doom paintings to create a strangely humorous and oddly enticing image of the Netherlands. Bosch was warning viewers not to be too tied to earthly pleasures, and yet looking at his painting is so much fun. Despite the masterful composition, it is ugly—or at least, it contains bright spots of ugliness. It is dappled with barbarity and splattered with joy. Heaven, shown on the left side of the triptych, looks rather boring and notably empty. Hell, shown on the far right, has fornicators and flute-arsed musicians.

Bosch showcased how ugliness could be playful, but other Renaissance artists approached ugliness with a more serious and steady hand. When Leonardo da Vinci began his search for beauty through interrogating a “series of disgusts,” as historian Walter Pater termed it, he began by painting deeply misogynistic images of women (perhaps as a way to air out his disgust for heterosexual sex) and people with diseases and disabilities. These bruttezza drawings were intentionally unattractive; the supposed ugliness of these individuals was intended to contrast with the beauty of Leonardo’s other sitters. Quentin Matsys’s 1513 painting “A Grotesque Old Woman” can be located in this same tradition of “grotesques.” Known more commonly as The Ugly Duchess, this work shows a woman in a tight bodice and regal headdress. “The sitter is now diagnosed as suffering from Paget’s Disease,” explains Stephen Bayley in his 2011 treatise Ugly. Despite the fact that we now “know better,” than to gawk at the suffering of others, Bayley claims there is a “magnificent absurdity” to this painting’s popularity. It is, he notes, “one of the most popular postcards sold in London’s National Gallery Shop.”

Like church-perching gargoyles and vulva-spreading sheela na gigs, these paintings are curious outliers. For the bulk of human history, artists have been far more concerned with beauty and the heavens than the ugly and the earthly. Ugliness was used as shorthand for spiritual damnation, when it was shown at all. Philosophers, while concerned with questions of beauty and morality, have not often grappled with visual ugliness (though they’ve spilled plenty of ink on ethical offenses). “You can’t write a historical narrative on ugliness, at least not in the academic sense,” argues Bayley. “The books simply do not exist: appropriate to its aggressive nature, ugliness is a subject writers have generally avoided. Perhaps they have avoided it like a plague.”

Bayley does identify a few other peak eras for ugly art, including the baroque period, which spanned from around 1600 to 1750. During this time, artists were very into ornamentation, and every surface that could be fluted or gilded or scalloped or molded was, with a very heavy hand. Baroque artists were the OG maximalists. But while many consider baroque art to be rather unappealing or “ghastly” or “gag-makingly hideous,” as Bayley puts it, I have trouble calling this art ugly. The word baroque means “a deformed pearl,” yet there is order in most baroque art—the ornamentation and uneven surfaces on Francesco Borromini’s buildings do not appear at random, but rather undulate like a slithering snake. Caravaggio’s dramatic canvases feature classically inspired compositions and high levels of technical skill. They are extra, certainly, but they’re not really ugly. And for my money, Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne is the most beautiful sculpture ever created, so I suppose I quibble with Bayley’s distaste for the baroque. I certainly prefer it to what came next—the prettified fluff and saccharine frills of rococo-crazed Europe.

But slowly, these decorative phases fell out of style and, with the advent of Romanticism, European artists began to turn toward a more naturalistic form of painting. This coincided with a newfound desire to define both beauty and its opposite. In the early 19th century, theorists began approaching ugliness as though it were its own aesthetic category. In 1853, Karl Rosenkranz published one of the first deep dives, Aesthetics of Ugliness. This picks up the aesthetic baton from Hegel and attempts to figure out how negative aesthetic categories, like the uncanny, the grotesque, the ghastly, and the ugly, relate to each other, and how they differ. For previous generations, a mountainous landscape would have been viewed as rather ghastly—it was ugly simply because it was scary. The Romantics challenged this notion, and began to create scenery that was both beautiful and frightening (i.e. sublime). Casper David Friedrich’s paintings are an excellent example of this. They’re beautiful and frightening, but few would call these landscapes ugly. What had once been terrifying was newly approached as aesthetic, and so ugliness was pushed into another realm. The new home for ugly art became the big tent of the abstract.

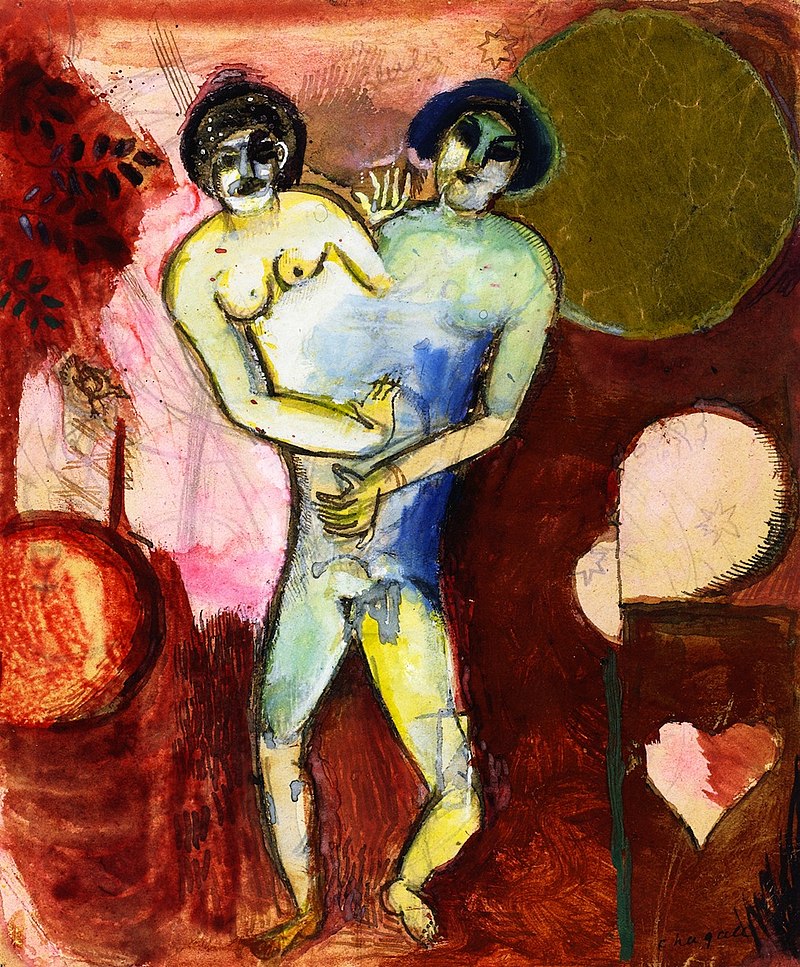

Even though today we’re perfectly capable of finding beauty in Rothko, when it arrived on the scene in the 19th century , abstraction felt like a deviant impulse. And as impressionism gave way to expressionism and the 19th century turned into the 20th, the impulse to label these artistic experiments as morally wrong or “degenerate” grew greater. In July 1937, the The Entartete Kunst (degenerate art) exhibit opened in Munich, featuring works by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Edvard Munch, Emil Nolde, Franz Marc, Lyonel Feininger, and Marc Chagall. Were these works ugly? Some of them were. But they were not nearly as ugly as the Nazi’s genocidal vision. The paintings were also part of a new art world, one in which categories of ugliness and beauty didn’t hold so much importance—at least, not to the makers. Some of these works were ugly, and that was the point. They were intentionally strange, surreal, and disorienting. They showed a chaotic and fragmented society; They were broken mirrors for a broken world.

In our post-modern or post-post-modern art world, it can be hard to remember why ugliness matters, because ugly paintings are now everywhere. Ugly paintings hang in every major museum, and ugly work has been accepted as part of the canon. But while ugly art crosses genres and time periods, it can still be useful to think of ugly art as falling into its own unified aesthetic category. Like zany, cute, and interesting, the three labels defined and clarified by Sianne Ngia in her book Our Aesthetic Categories, ugliness plays a pivotal role in art history and in contemporary design.

Unlike grotesques, that elevate their subject until it approaches the beautiful, truly ugly works aren’t about pleasing anyone. Ugliness is about discomfort. It makes us feel a little unsettled—not because we’re looking at a depiction of something unsettling, like with a gory religious scene or a photograph of a war zone or a painting of a warty nose, but because we’re confronted with a sense of disorder.

This can be intentional, or it can be the result of badly applied technique or poorly chosen colors. Typically, the ugly art we see in museums was made that way consciously, either to highlight the artist’s abilities (like with Leonardo’s elegantly drawn caricatures), to rebel against the conventions of the art world (for example, Philip Guston or contemporary painter Neil Jenney), or to reveal something about the world and our place in it (Hieronymus Bosch, Otto Dix, and Francis Bacon and their stomach-turning depictions of bodily pain).

Frank and his colleagues at the Museum of Bad Art don’t collect the kind of significant “ugly paintings” that the New York Times might write about or the Met might display. Instead, Frank uses his aesthetic judgment to choose works that feel compelling. “I reject anything that is uninteresting,” he says. “Uninteresting work is unacceptable. If something is silly, or if it was made cynically in an attempt to get into the Museum of Bad Art, than I’m not interested.” He’s also not interested in kitschy pieces or commercial art, like black velvet paintings or taxidermy sculptures.

There’s a sense of brazenness to unintentionally badart—it embodies desire gone awry. And being able to enjoy ugly art isn’t simply about making fun of it. It’s also about being able to sit in discomfort and recognize mistakes. Ugly art demands a sense of looseness; it asks the viewer to dip into a slippery mind state where you can hold multiple beliefs simultaneously. The piece can be both ugly and unappealing, and it can also delight and appeal for those very reasons. It can pull you closer—you want to know why this ugly art was made, what it means, and what the artists were thinking. And if you let yourself get unbalanced enough, you might just find yourself a little bit in love. “If you go on social media, you’ll see the most common comment I get,” says Frank. “People are always posting, ‘I like it.’ Or even, ‘I like this painting, it shouldn’t be here.’”

Frank often responds, “I like it, too. That’s why I collect this art. I like it.”

Katy Kelleher is a writer who lives in the woods of rural New England with her two dogs and one husband. She is the author of Handcrafted Maine.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2mY4LvN

Comments

Post a Comment