The color grey is no one’s color. It is the color of cubicles and winter camouflage, of sullage, of inscrutable complexity, of compromise. It is the perfect intermediate, an emissary for both black and white. It lingers, incognito, in this saturated world.

It is the color of soldiers and battleships, despite its dullness. It is the color of the death of trees. The death of all life, when consumed fire. The color of industry and uniformity. It is both artless and unsettling, heralding both blandness and doom. It brings bad weather, augurs bleakness. It is the color other colors fade to, once drained of themselves. It is the color of old age.

Because I have no style, I defer to grey. I find it easier to dress in grayscale than to think. I buy in bulk, on sale, in black and white and shades between—some dishwater desolate, some pleasing winter mist. I own at least five cardigans in grandpa grey.

My mother always called me plain. She saw this as a flaw to be corrected. She wanted the whole world dressed in dazzling color—even me. I never quite complied. I have the fashion sense of Vladimir and Estragon and the panache of my New England nana. When left to my devices, I choose to be unobtrusive. I choose grey. It suits my diffidence and soothes my extroversion. It is the color, rather than the sound of silence. It sits, with monkish, folded hands and asks for nothing. It never shouts. It never pushes. As the French painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres said, “Better gray than garishness.”

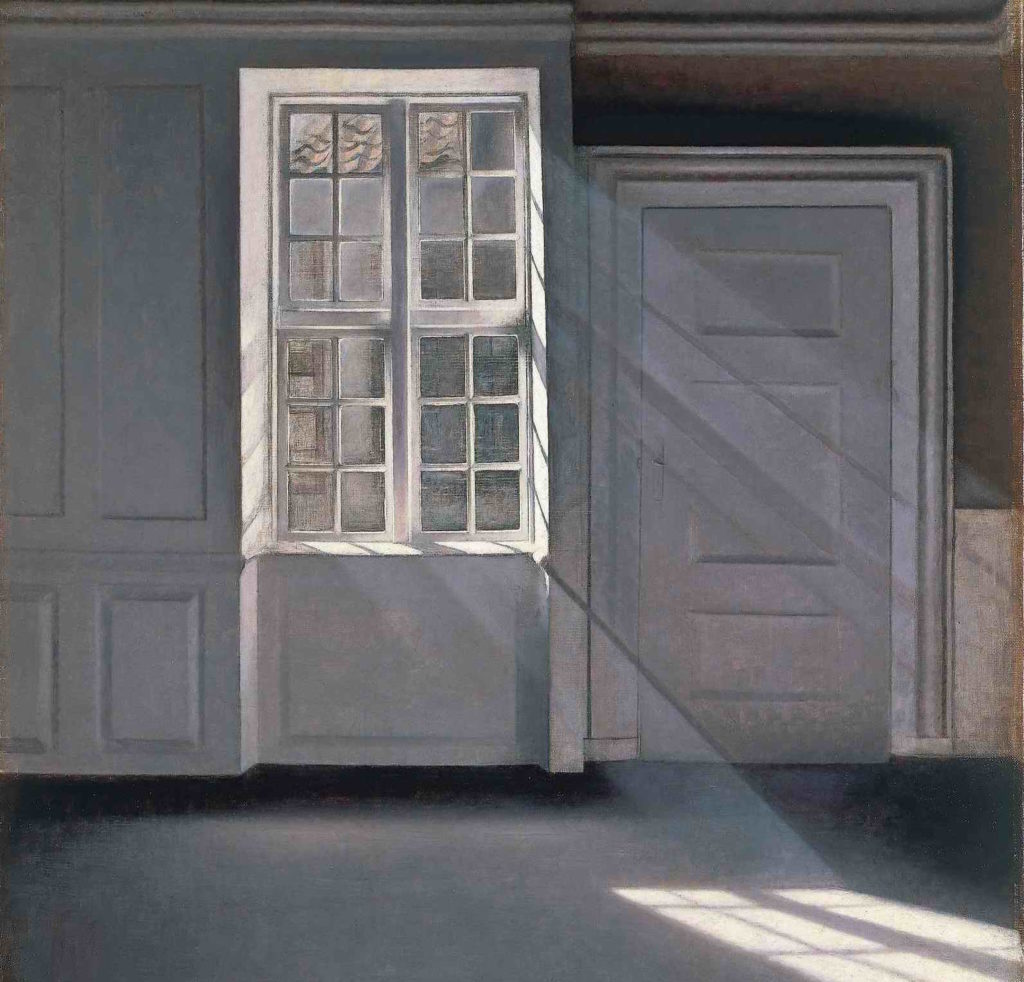

I’m drawn to grey, as to a dream, but not to any old grey. Not stormcloud grey or corporate monolith. I prefer tranquil grey: the undyed wool of sheep in rain, the mood inside a Gerhard Richter painting, the mottle of an ancient cairn. I don’t mean any one grey either, but the entire under-rainbow of the world, the faded rose and sage and cesious. Liard, lovat, perse. The human eye perceives five hundred—not a mere fifty—shades of grey. Paul Klee called it the richest color: the one that makes all the others speak.

*

Ask any schoolkid to list the colors of the rainbow, and she’ll sing-song you through your ROY G. BIV. Seven colors: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. Newton started out with five, then added orange and indigo to sync with music—one for every step between one tonic and the next along a major scale. (Aristotle had seven colors also, but his scale stretched from white to black, not red to violet, and included yellow, crimson, violet, leek-green, and deep blue.) Then there are the eleven standard colors taught in schools, who add black, white, brown, pink, and (my beloved) grey. It feels like an addendum, consolation for a color overlooked and undersung.

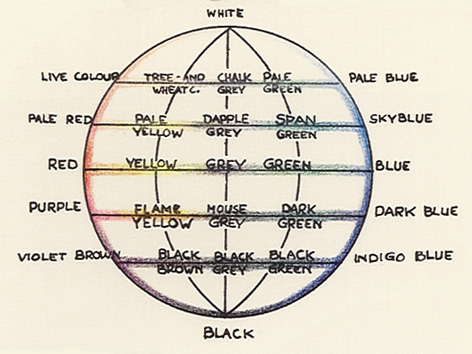

Before Newton, there was Aron Sigfrid Forsius, a seventeenth century Finnish astronomer who made a color wheel into a sphere. He chose five colors: red, yellow, green, blue, and— stretching through them all like ligaments—grey. In Forsius’s model, white and black are polar. His five colors span longitudinally, pale in the northern hemisphere, dark in the south. The prime meridian of this color globe, of course, is grey—the lovechild of the poles. It is also the color through which all other colors pass. At the center of all color, then: a mass of multicolored grey.

According to Eva Heller, in her Psychologie de la Couleur, only one percent of people surveyed named grey as their favorite color. I feel, therefore, unique in my perversity. As though I have befriended someone hard to like.

A color psychology article on Bustle tells me that I fear commitment. “Grey is emotionless,” it says—“boring, detached, and indecisive. Those who say their favorite color is grey don’t tend to have any major likes or dislikes.” (False. I majorly like grey.) Lovers of grey “lack the passion that comes with loving a ‘real’ color.” And yet I yearn for it. I fill my drawers with grey brassieres. I dress my bed in sheets and duvets like a day with all the blue drained out of it. The tidiness, the monochrome, inspire peace.

Heller deemed the color “too weak” to be considered masculine, “too menacing” to be considered feminine. It is neither warm nor cold, neither material or spiritual. It can’t make up it’s mind; perhaps neither can I. Grey is the endless ‘and.’ It can be cooled or warmed, made magic or mundane. It’s almost always tinged with color, but nothing quite so bold as to commit.

It is also, at least since the first printed photograph in 1826, the color of experience, or what we mean when we say “black and white.” Photography has long been our record of the world. The medium that tells the whole, unrepentant truth in perfect detail. And yet, for decades, no one seemed to mention what was missing. We were all content with the desaturated version: the texture of reality rendered not in black and white, but in (five hundred) shades of grey.

As the black-and-white photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson, once said to the color photographer, William Eggleston: You know, William, color is bullshit. In the realism of the black-and-white, grey is every color—without the tartishness. The understudies take the stage and no one seems to miss the headliners. We see the world without distraction. Andre Gide called it the color of the truth.

Look at enough black-and-white photography and color comes to feel like an intrusion. Eggleston’s photos seem too vital to be real, as though depicting an alternate reality. Each image is delirious with hue, spectacular, delicious, but a little bit too much. The eye craves rest, and mystery—the kind of truth that can be searched only in subtlety. Dorothy may tumble, tornadic, into Technicolor, but still she always wishes to go home.

*

We assume, wrongly, that grey is flat; we’ve been conditioned to do so. Even Wittgenstein denounced it, found it lacking luminosity. But his grey was conceptual, a fiction. As David Batchelor would write: A grey of the mind is largely an absence—of colour, of interest, of warmth, of desire, of life—whereas a grey in the world is always a presence. Goethe might be right that grey “is all theory” because theory itself is grey; the theory of grey, therefore, is also grey. The reality is of grey is not.

Grey in the wild opens and spills. Put two greys together and you’ll see the color each one hides within, the “endless variations” noted by Van Gogh. I think of the handful of river pebbles I once snuck into my pockets on a day trip to a waterfall: they were dusty grey when I got home, but, under water, each concealed a secret separate life as green or red or blue. So many things that seem grey on the surface have a treasure to unlock—myself, I hope, included.

Bauhaus painter Johannes Itten wrote that grey is mute, but easily excited to thrilling resonances. Infuse it with a touch of any other color, and it transforms itself from “sterile neuter.” You don’t expect to find emotion in the grey, but there it is. Beneath the “dampness, dishwater and disappointment,” there it is. Surprise.

*

Where I live in California, the good weather is oppressive—with each day bluer and more vivid than the next. Sometimes, the rare grey morning dawns, clouded and tenuous, and the world is hushed. I only hear the doleful hooting of the Zenaida macroura, the bird who understands me best. By noon, inevitably, sun and cyan have burnt through. The great brass band of color strikes up once again. Flowers perk up; leaves are lit ablaze. Here, in living color, Kodachrome, the glory of the world. I fight a pang of mourning for the leaden sky, as though a friend has left.

I sometimes drive an hour to the ocean, hoping I will find it thoroughly obscured by fog. I am not a melancholic, or a bore, but I want a break from all the rainbow violence in the world. To scratch beneath the surface to the quiet central core of Forsius’s color sphere.

Derek Jarman wrote: Grey is the sad world into which the colors fall. But he also wrote that grey is where color “sings.” It is the perfect neutral, balanced, dignified—and yet it is so effortlessly swayed; it is the sponge that soaks up other colors as they bleed. It compliments; it brightens light, and lightens dark. It isn’t flat. It’s deep, endlessly deep.

Grey is the dark end of the light. The light end of the dark. Unsettling, perhaps, but full of possibility. Just think how beautiful we all look in the gloaming. It’s liminal, the color of our own potential to become.

Meghan Flaherty is the author of Tango Lessons (HMH). Her essays have appeared in The Iowa Review, Psychology Today, and online at The New York Times, The Rumpus, Catapult, and elsewhere.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2LgbVp3

Comments

Post a Comment