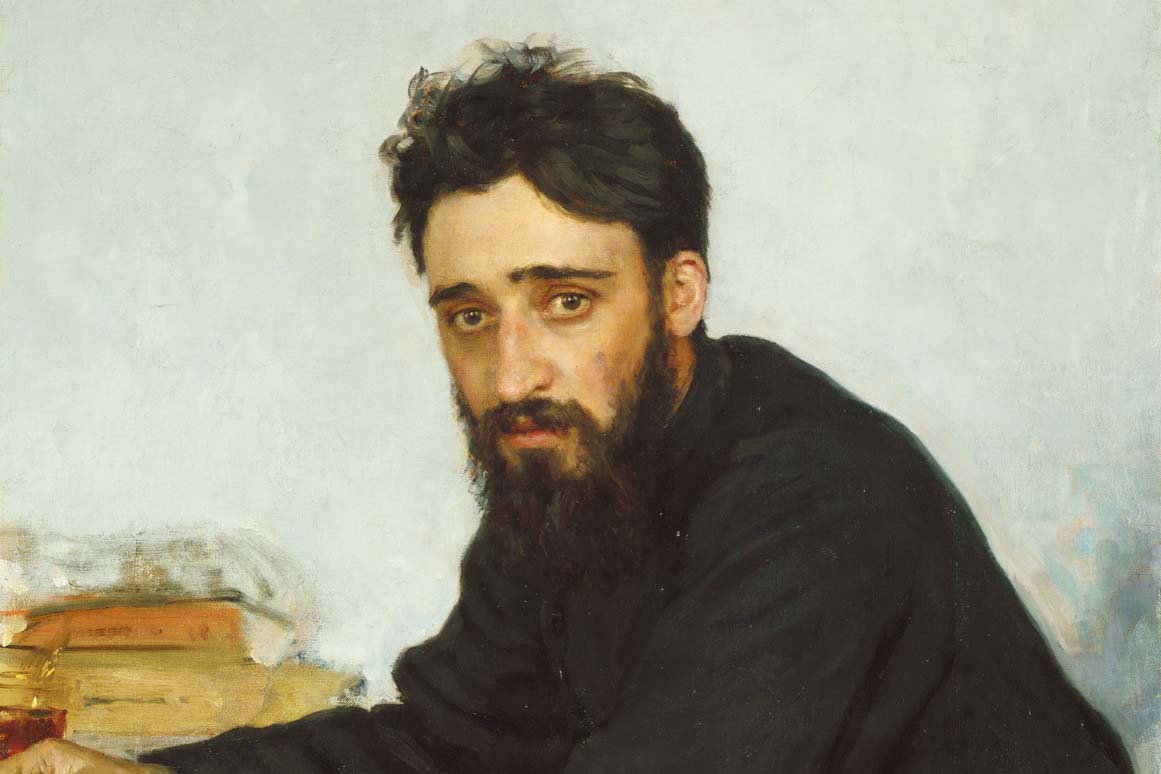

It is my habit, wandering through the seemingly logicless branching of the Met’s European Painting rooms, to collect body parts from portraits, to take certain striking features and make them a synecdoche of the genius of their painter. Goya, for instance, is a masterful painter of hands; the Dutch painter Frans Hals is one of the great artists of the mouth. The course of this habit, though, always leads me to one painting in particular, featuring the most living, searching, despairing set of eyes I have seen in a portrait—the Russian painter Ilia Efimovich Repin’s portrait of the author Vsevolod Garshin, in Gallery 827 at the Met. Most of the painting is rendered in the smudgy, conspicuous manner of nineteenth-century Impressionism, but the eyes are almost frighteningly photo-realistic, as if Repin had intentionally blurred the rest of the picture for the shock of the eyes, their bracing directness and incontrovertible sadness. Entirely redundantly, the caption informs us that Garshin would throw himself down a stairwell four years later. Portraiture is usually a contest—the subject wants to modulate, manage what they give away, while the artist wants everything. The eyes, in Repin’s portrait, are where that contest collapses, a tear in the fabric where Garshin’s unadulterated self floods out and buries Repin’s brush. —Matt Levin

The “Obsession” exhibition at the Met Breuer deftly straddles the line between art and obscenity, featuring mostly nude female subjects in the fifty-two works of Gustav Kimt, Egon Schiele, and Pablo Picasso. The audacious exhibition takes after its curator, the infamously obsessive aesthete Scofield Thayer, who, in addition to his eye for erotic art, held sway in the literary world—in 1919, he cofounded The Dial, an avant-garde magazine that introduced the writings of T. S. Eliot, D. H. Lawrence, and Ezra Pound. Several pieces in Thayer’s collection—in particular, the portraits by Schiele—are overtly evocative of Freudian themes: the blurring of pain and pleasure, the morbidity of sexuality, the “suffering [of] lust.” Schiele’s works display emaciated and deformed bodies which he somehow make beautiful. Klimt, Schiele’s predecessor, also explored bodies that were less conventionally attractive: the obese, the elderly, the “real.” Both of these artists, like Freud, take an almost clinical approach to female sexuality. Several years later, Picasso offered his own take on the nude with sketches of both male and female villagers from his time in Gosól, France. Although the focus of the exhibit is on the aesthetic of the female form, it is also an excellent opportunity to consider the prominence of the male artist’s gaze and how it has changed—and how it hasn’t. —Madeline Day

The latest issue of Granta is “an issue on gender and power” and the first line of Sigrid Rausing’s editor’s note refuses to mince words: “This issue of Granta is about patriarchy, and some of the ways in which our gendered culture is now creakily changing.” The more concise theme on the spine reads “generic love story,” which piqued my interest—to tie so intimately the patriarchy with normativity struck me as yet another bold move. I picked it up only yesterday, but I’ve been absorbed by a short piece by Ottessa Moshfegh that is sharp and frank about the relationship between power and sexuality. The first story is a personal essay by Fernanda Eberstadt, titled “I Bite My Friends,” about her intense friendship with the downtown drag queen and performance artist Stephen Varble. It sets a tone of engaging with the issue’s themes in the complex ways they deserve without forcing anything into a straightforward resolution. —Lauren Kane

PUBLIC WORKS Musical Adaptation of William Shakespeare’s TWELFTH NIGHT. Patrick J. O’Hare (L), Shaina Taub (center), and Shuler Hensley (R) with the BLUE community ensemble rotating cast. Photo credit: Joan Marcus.

Utopia is regained every night this week at the Delacorte. As the audience sits for the community production of Twelfth Night, screens flanking the stage announce the need for new expectations “closed captioning happens in Illyria.” Here like a solicitous hostess, the Delacorte anticipates everyone’s needs. As Shaina Taub, the show’s lyricist and composer, merrily warbles from stage to orchestra under a dripping plastic tent, the summer camp morals of my childhood joined the New York of my dreams. Where else does the audience so closely resemble the cast, so closely resemble the boulevards? The Public Works production involves nonprofessional participants from organizations such as The Brownsville Recreation Center, The Casita Maria Center for Arts and Education, and Children’s Aid Society. The story is Shakespeare—loosely. The audience is fully rapt. Twelfth Night is the reminder of fraternity in this summer of fracture: play on. —Julia Berick

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2Mzsm4q

Comments

Post a Comment