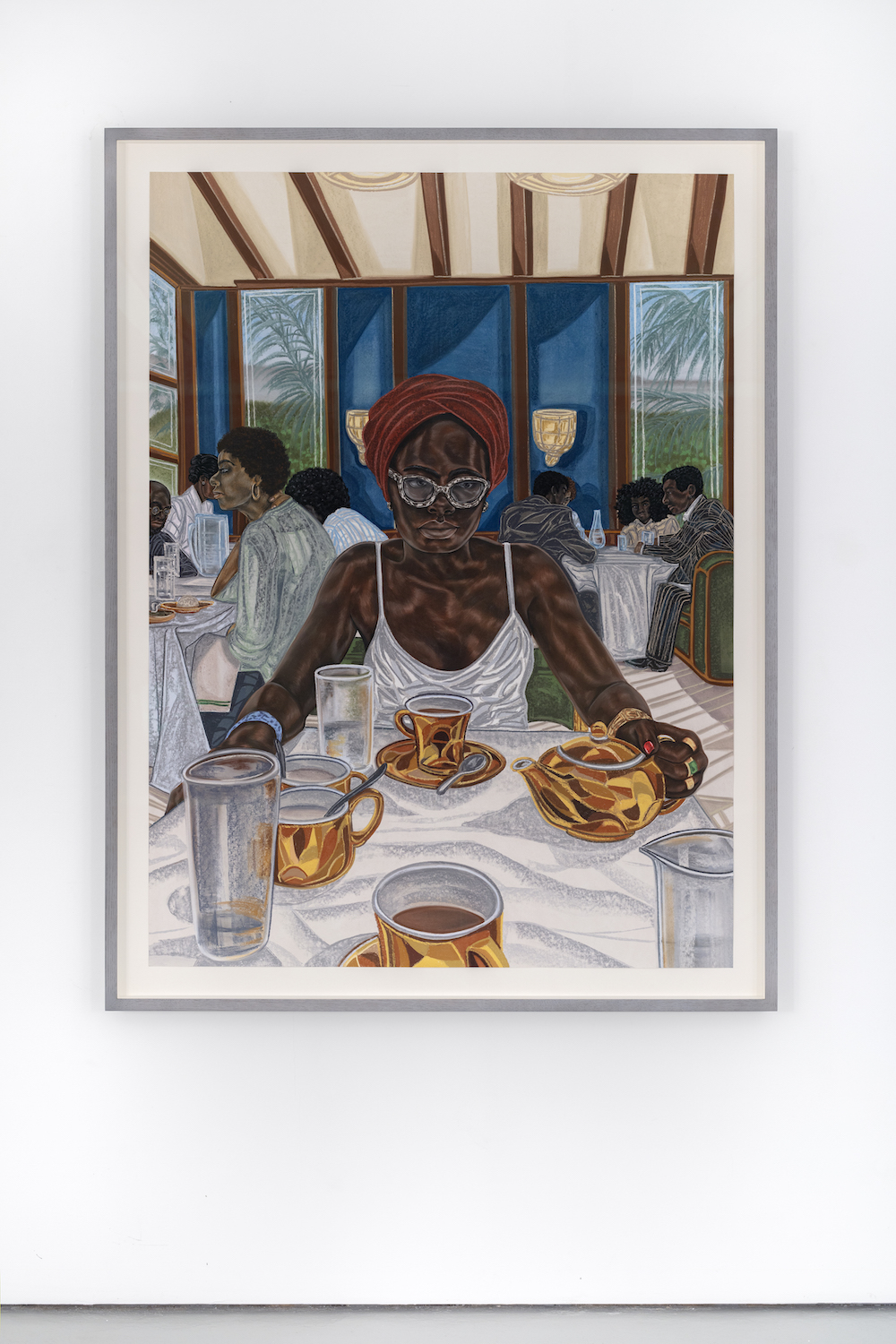

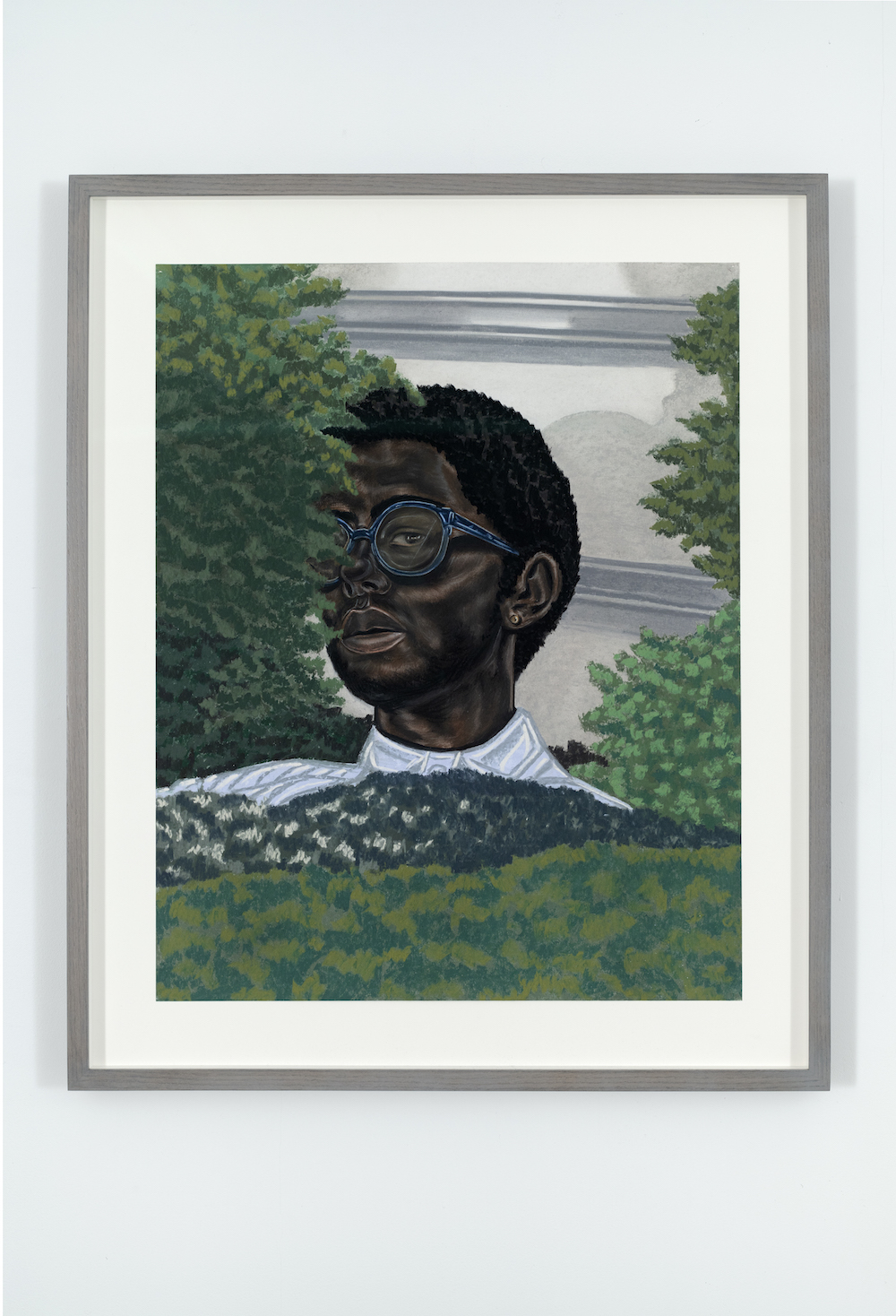

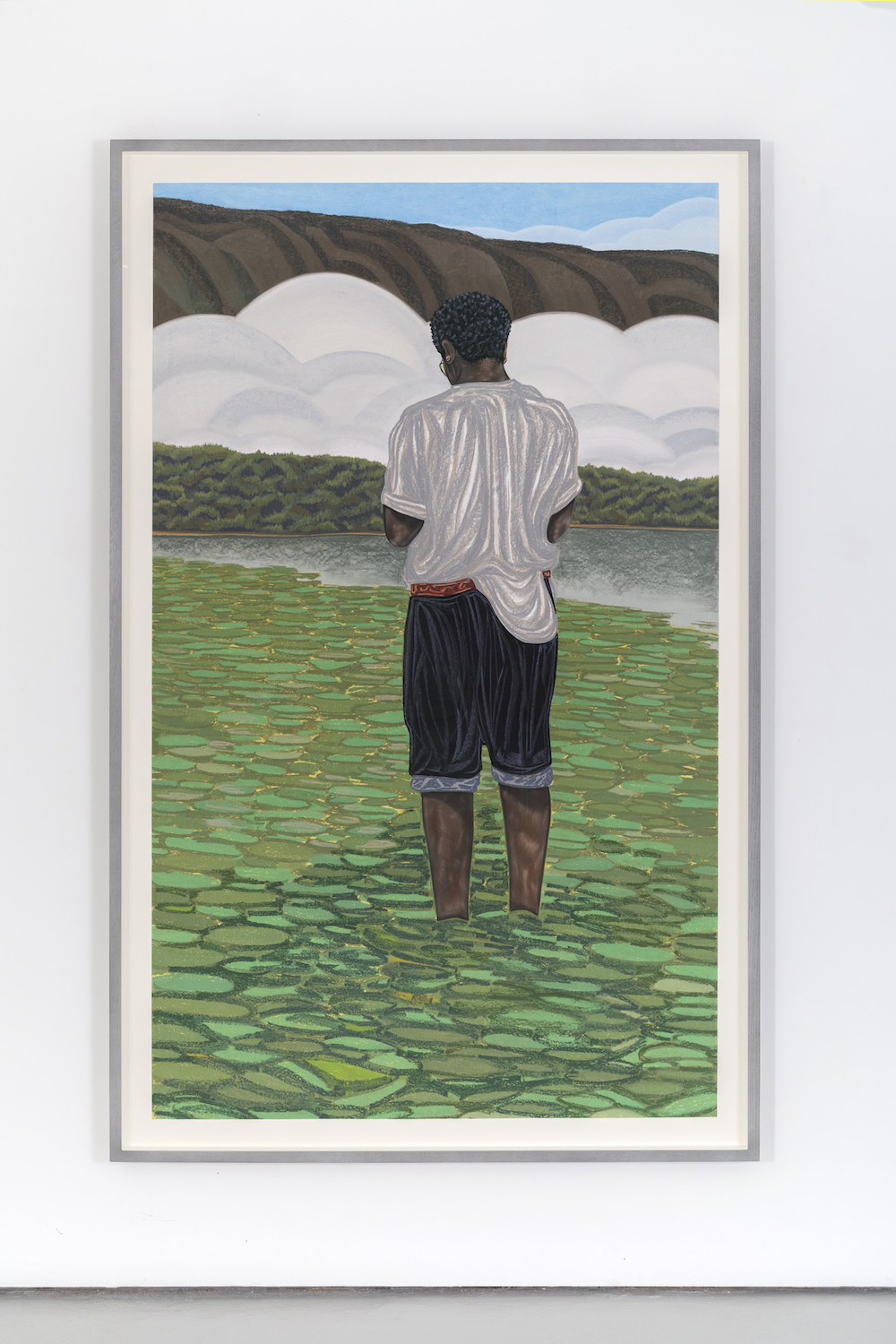

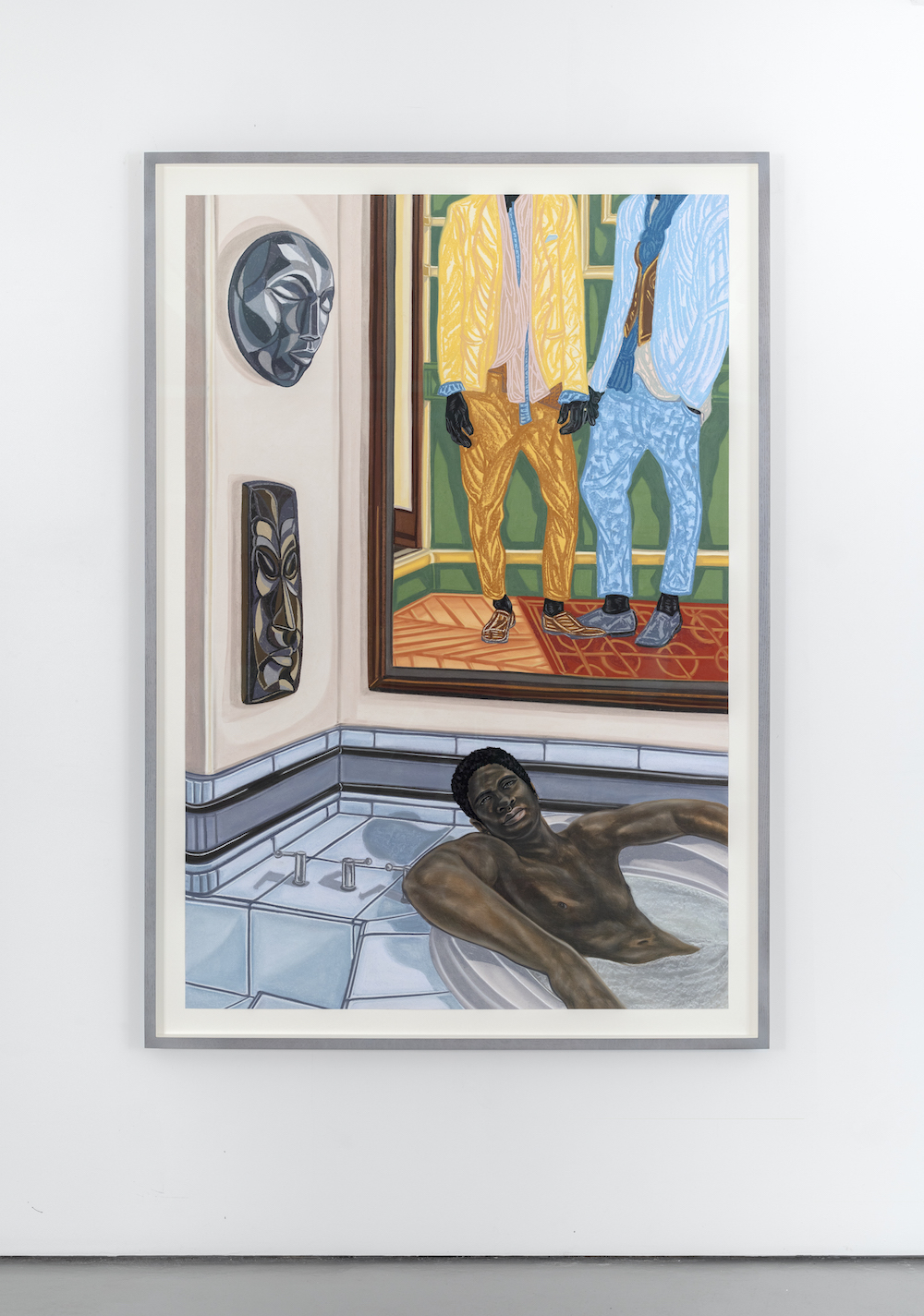

“There is no story that is not true,” says uncle Uchendu halfway through Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. Storytelling is at the core of Brooklyn-based artist Toyin Ojih Odutola’s drawings, which center on the fictional narrative of TMH Jideofor Emeka, male heir of a long-standing noble clan, who marries Temitope Omodele, the son of a bourgeois family with recently-acquired wealth. The power couple are the cultural leaders of their community, and they exhibit their renowned art collection at notable art venues in the United States. Ojih Odutola deepens the fiction by presenting her own exhibitions as curated by the fictional couple, for whom she is the Deputy Private Secretary.

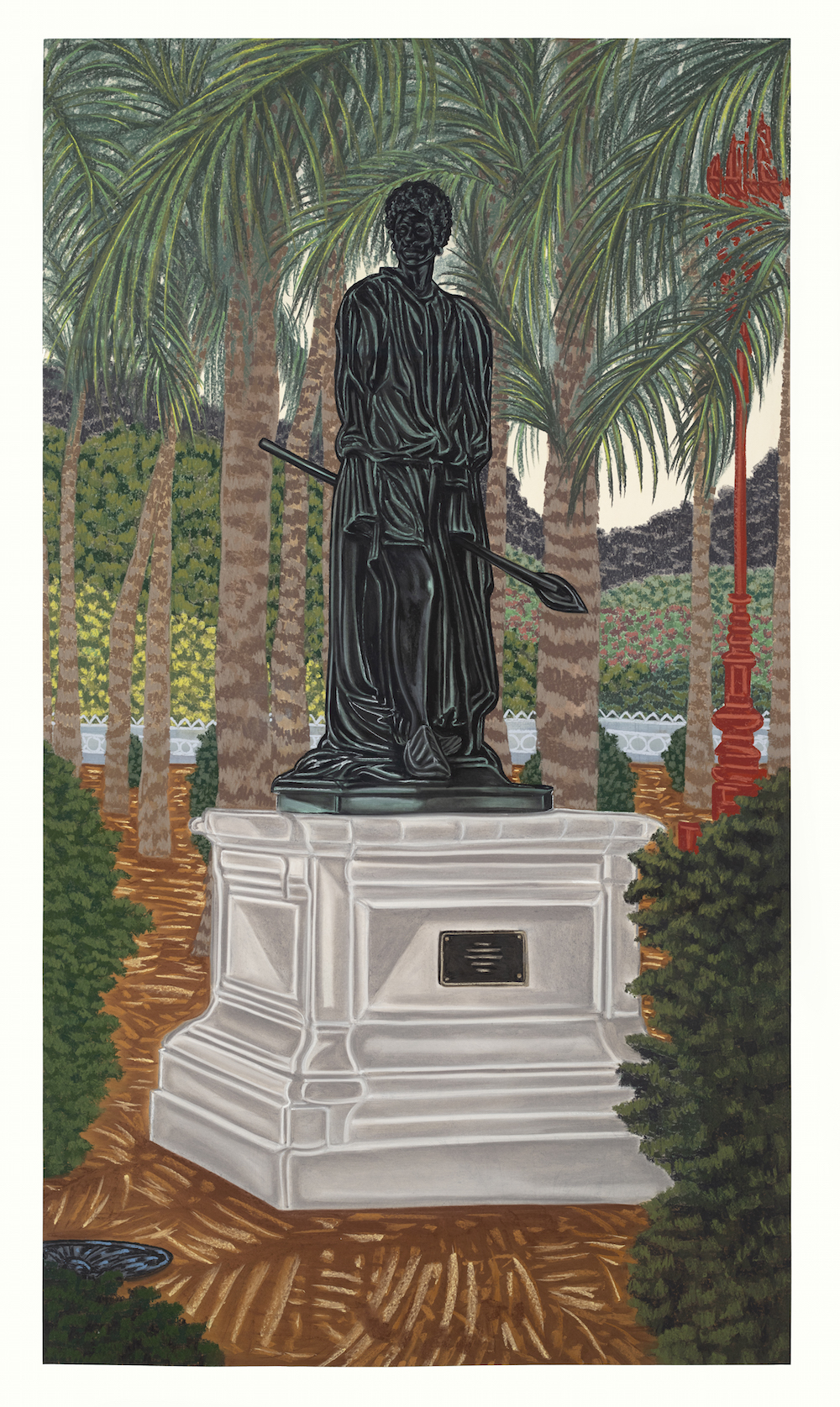

The thirty-three-year-old artist left Nigeria with her family at early age, and spent her formative years in Huntsville, Alabama. Her new show, “When Legends Die,” at the Jack Shainman Gallery in New York, dedicates two rooms to approximately thirty-five drawings. The press release, written by Ojih Odutola, explains that the show is organized by the lord’s nephew upon the aging couple’s decision to include the next generation of clan members in their curatorial work.

I met Ojih Odutola at Jack Shainman Gallery in August, when the artist was busy finalizing her drawings for her exhibition at the gallery.

INTERVIEWER

Storytelling is a crucial part of your practice. Do you pen your stories before illustrating them?

OJIH ODUTOLA

I don’t consider myself a writer. My writing is as episodic as my drawings. Once I sort out a story’s outline and key themes, I select the scenes I want to explore more deeply, and they eventually transform into sketches. At this point I’ll also focus on research about a specific time period in Nigeria. With that scaffolding, I delve into plot points and build out the characters’ relationships to one another. Depending on how complex a particular drawing is, I’ll do ten to twenty sketches. I am weaving something I hope is not necessarily about text, which is like a safety net for me, but rather about a visual language with cues that words cannot supplement. However, I need text to give me the permission to draw. They are two intertwined paths.

INTERVIEWER

In the narrative background you provide for the work, you relinquish your authorship.

OJIH ODUTOLA

I wanted to distance myself, as Toyin, from the work. When I started this series in 2016, I was wary of how even the fictive work I invented was still about me as an artist of color. My otherness often precedes the content of the work, almost like a cloud before the viewer. Once I became the Deputy Private Secretary on the press release, the viewer stopped looking into my involvement and tried to grasp the story. I was freed from the distraction of the story somehow being about me. With this new role, I have the freedom to say, “I am the communications liaison between the public and this family, but I can only reveal just enough amount I find necessary.” The work is not about a mythology or a presumptuous idea about African-ness. The viewer is immersed in the narrative, an alternative reality. For example, the story’s key figures are two gay men, although, in reality, it’s illegal to be gay in Nigeria.

INTERVIEWER

The marriage of these two men anchor the entire story. How did you decide to place two gay men in positions of power?

OJIH ODUTOLA

This is actually a very matriarchal family, but two men comprise the core. I had the idea of a gay couple coming into power since the very beginning—even before I had any concept about the families. The beauty lies in the fact that whatever happens in each chapter, they’re the reason we are in the room; there would not be an exhibition if their love did not exist, and if they didn’t loan their collection. I always want to underline this role they possess; the words “his husband” are always very evident in exhibition materials. When my father saw those two words at The Whitney, he asked, confused, if there was a typo. Seconds later, however, he wanted to learn about their story, and asked me to take his photo with a painting of theirs. I hear people say they carry those two men with them outside the exhibition; the idea of their union becomes less of a fantasy, but rather a reality where Goodluck Jonathan never signed the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act for imprisonment of LGBT individuals in 2014. I had initially planned to create the series only about them, but I began to realize the beauty is in not only in their union, but in everything that stems from that—just like being gay itself, it opens up to other possibilities.

INTERVIEWER

Can you tell me about the decisions you have made in the shifting skin tones in your images?

OJIH ODUTOLA

A character in three different stories has three different skin tones. They are different reverberations and tones of the same skin reflecting that experience. Skin is a place we inhabit and have to mitigate while moving through the world. Over various iterations, I transitioned from charcoal skin to pastel. Instead of every figure having the same patina, they’ve gained multi-tonal diversity. I want to skin feel more alive and distinctive for each character; I felt my hand gestures change. I am aware of their painterly quality, although they are strictly drawings. The skin also evolves with age, which is visible in the current exhibition with most characters reaching their 40s and 50s and fresh young faces making their debut. Although the previous iterations have been chronologically slippery with light references to 1970s and ‘80s’ stylistic accents, this final iteration clearly brings the story to the present. The notion of experience relates to freedom of travel, which these characters own. How do you capture experience in a drawing? Again, with the skin. Creating a face or skin extends to the surrounding of the character; the space is activated, almost coming out of the surface into real life. I am committed to illustrating the freedom to be in a body and move through space.

Toyin Ojih Odutola: When Legends Die remains on view at Jack Shainman Gallery through October 27, 2018.

Osman Can Yerebakan is a New York-based art writer and curator. His writing has appeared in New York Times: T Magazine, Village Voice, Brooklyn Rail, BOMB, CULTURED, GARAGE, Galerie Magazine, Amuse, Elephant, Harper’s Bazaar Arabia, and L’Officiel.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2NKVkjh

Comments

Post a Comment