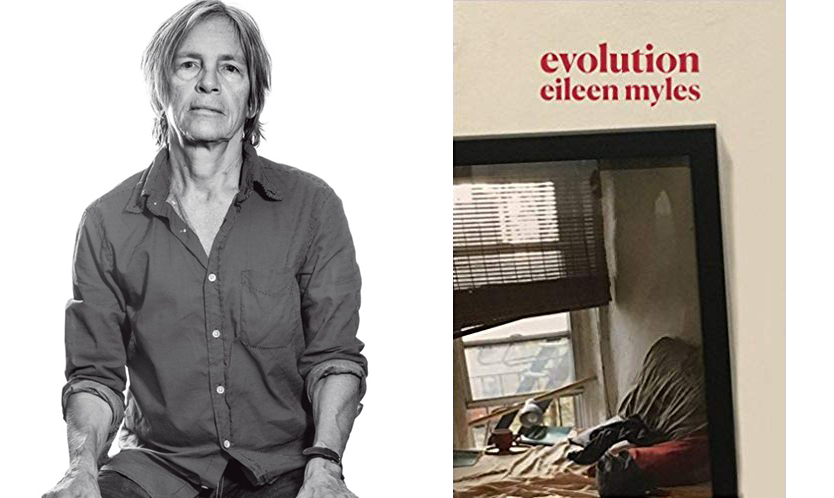

Eileen Myles may be the closest thing we have to a celebrity poet. In part, Myles’ stardom can be attributed to the award-winning television show Transparent, in which a queer poet played by Cherry Jones was based on the character of Myles. But while Myles’ stint on television (in addition to serving as poet-muse, Myles made a cameo on the show) may help to explain their rise to a level of celebrity usually out-of-reach for even the most successful poets in America, Myles’ stature has been decades in the making. In addition to producing more than twenty volumes of literary work, Myles famously ran a write-in campaign for presidency in 1992. Among their most oft-cited poems is “An American Poem,” in which Myles identifies as a Kennedy, one who forsook the wealth and comfort afforded by a famous, successful American family, for a life of poverty and obscurity as a poet in New York. In real life, Myles grew up in an Irish-Catholic blue-collar Boston family. Much of their work, including the legendary Chelsea Girls, reflects on Myles’ childhood and the poetry scene of New York in the 1970s and 80s. The last few years have been especially prolific for Myles, whose new book, Evolution, a collection of new poems, comes on the heels of last year’s Afterglow (a dog memoir), which had in turn followed another volume of new and selected poems as well as a new edition of Chelsea Girls.

I’ve long admired Myles’ work, and taught their poems in a course on feminist poetry earlier this year. Current events, and our political milieu made me especially keen to speak with them. We spoke over Zoom (a video conferencing program), Myles from their living space in Provincetown, where they were teaching, and I from the living room of my Stanford student housing unit. Myles was totally present, forthright and willing to engage with me, but also pushed back more than once. When I asked about the intersection of poetry and politics Myles responded: “what do you mean?” They forced me to reconsider not only how I was formulating my questions, but what, in fact, was behind those questions in the first place.

INTERVIEWER

Why don’t we start with the title of your new book, Evolution. What made you choose this title?

MYLES

The title is really simple. The first poem in the book is called Evolution, it’s a long poem that has a lot do with what the book is doing, which is a certain way of approaching the unknown. I love the word evolution because it holds a lot, and is very uneven. Evolution doesn’t come in a constant way, it comes in spurts. It could be that a lot happens in ten minutes, and then nothing happens for ten thousand years. I was in New York and I had more free time than I usually had; I didn’t yet have a new dog. There was a quaking and interesting emptiness in my life. The poem took that space, and asked questions about sanity and craziness and communication and neighborhood, really big general questions about life and existence.

INTERVIEWER

In that title poem there are several lines about going crazy, or being crazy. For example, you write: “My thighs./ I’ve had you since/ I was a kid./ I’ve known you for so/ long. Even when/ you betrayed/ me in the bathtub/ one night when/ you were rabbits/ but that’s cause/ I was going/ crazy. Is it crazy/ to be the/ citizen who’s/ only partially here” What is craziness, and what does it mean to be “only partially here”?

MYLES

I think being partially here is a very contemporary condition. When I’m talking to someone over a counter, or on a technological platform, we’re sort of connecting but we’re not in the same space—it’s a mysterious immediacy. When I wrote the part about thighs and rabbit ears in the bathtub, I was hearkening to a point in my early twenties when I felt like I was holding onto my sanity by a thread. Obviously crazy is the word men use whenever a woman says something they don’t like. It’s crazy! Is she crazy? You think she’s crazy? I heard she’s crazy! I was trying it on a bit, while also alluding to a moment when I felt that I was going crazy. I was coming into existence and that was scary. I think every time you transition in your life in a way that feels radical, it’s a bit of a dance between craziness and evolution.

INTERVIEWER

What or where is the here of “partially here”?

MYLES

Here means connection. Here is the most desperate and primary word we have for marking a point, occupying it and holding onto it (Myles bangs on table for emphasis). We know what here means when we’re there.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think of yourself as a political poet? How do politics inform your work?

MYLES

I think adjectives are a little troubling but I’m not uncomfortable with dealing with politics in my work. Politics aren’t anything I or anybody else successfully shies away from in their work. I mean, by not mentioning politics you’re doing something pretty clear.

INTERVIEWER

One of the highlights of this book is your presidential address, “Acceptance Speech,” written shortly before the 2016 election, in which you respond to Zoe Leonard’s poem “I want a Dyke for President,” which was itself written in response to your “An American Poem.” In “Acceptance Speech,” you outline what I take to be your utopian vision for the world, or at least for this country. There’s a department for women, a massively increased NEA budget, and many programs to encourage people to appreciate their surroundings. Education would be free, cars would be banned, there would be free food. Obviously we’re very, very far from this now. What do you think poetry offers us, particularly at this moment, given what’s going on in this country today?

MYLES

It always offers us the same thing: an opportune space to list things in an order that makes sense to you. Poetry is this kind of speech or statement that plays by its own deck. You can change the order, you can change the look of it on the page, you can use the right words, the wrong words, you can use English words, you can use words from other languages, you can appropriate languages. It is a utopian space in which to express. Poetry is structured like music, through gaps. But it’s language and I think that’s part of what’s upsetting to people who feel intimidated by it. They know what language does and now it’s doing something else. It’s also kind of the opposite right now. Because the world is pretty scary, and because of the way we use twitter or instagram or texting, the ways that language is compressing and expanding and occupying space are very different than they were 20 years ago. Poetry has always resembled that, so it’s easy for poetry to be a comfortable space right now. But if you are simply concerned with already knowing, you may not want to know what poetry knows.

INTERVIEWER

What does poetry know?

MYLES

There is no answer to that. It’s like all the ways of knowing. Each poem is a piece of information and communication of sorts. The point is that I think the form of it is always different and that is what is destabilizing.

INTERVIEWER

How do you see poetry as potentially being a political intervention?

MYLES

My work is that answer. They’re made of the same stuff. Politics is discourse. Donald Trump, to my mind, is a certain kind of performance artist who thrives on impact and confusion and destabilization. I can’t help seeing him as sort of a frustrated artist, with those same tools brought to a different use.

INTERVIEWER

There is an historical affinity between prophecy and poetry—do you think poetry is a form of prophecy? Do you see yourself as a kind of prophet?

MYLES

I think language is prophetic. It’s just like the I-ching, it’s just like the horoscope, it’s just like every kind of divination. It becomes a space that’s really alive and it starts to tell you things. Language is the prophet and I happen to be a human being who uses language regularly and so I know stuff because of my practice of drawing my words down.

INTERVIEWER

How do the words come to you? Where do they come from?

MYLES

I don’t make up any words; I use the words that are in the world. I think we all have incredible capacities to be prophetic, to be deeply sensitive and aware. I’m a thinking animal and for me language is the material. I like making arrangements. It all seems magical to me, kind of chemical and even alchemical. I always think about the Beatles in that they were not exceptional musicians, they were just kind of ok, they were sort of good enough and yet them coming together was an astonishing thing. Every time that happens, whether it’s a theatre troupe or people falling in love or a poem coming into being it’s like, what the fuck is that?!

When I taught at the University of California San Diego, I taught a class called Distributing Literature. I made it into a real workshop: people in the class were asked to invent a new method for getting poetry into the world. Two women in the class took a terrific, short, lyric poem by Michael McClure. They put the words on refrigerator magnets and they had a kind of flat palette and they went around the campus and found people who worked on the campus, in janitorial, in the cafeteria, in tech, everybody other than students and teachers. They said: would you make a poem out of these words? What they showed was that one perfect little poem contains so many other variations. I found it an unforgettable realization that nothing ever really lands, nothing is ever really fixed. It’s kind of a beautiful accident each time. I feel like that’s the business I’m in, and that’s what excites me about poetry.

INTERVIEWER

You work across genres. Do you have a preferred genre? How do you feel about genre categories altogether?

MYLES

I have very little respect for them. It’s like gender, it’s much more blurry and things are always entering into other containers. Poetry is the first genre that I was competent in and the first thing I could realize, so I give everything to poetry and describe myself as a poet. When I was inventing myself as a writer, I would read biographies and have ideas about writers. If a writer was also a literature critic, then I wanted to be a critic too, and if a writer wrote a libretto, then I would write a libretto and if I saw that you get drawn into Hollywood, then I wanted that to happen to me. You write a novel—you get a house it, seems. I wanted to get a house and I wanted to write a novel. I wanted to be a bourgeois writer. Part of my understanding of being a writer was that I thought all these other ambitions were intrinsic to it. Also, I’m kind of restless. If I’m writing a novel it seems like a very good time to write a poem, and if I’m supposed to be writing an essay and I have a deadline, then I’ll start thinking of the first line in a story. It came out of avoiding reality, in a certain way. I’d have a crumby part-time job and I’d be writing a poem on my counter or I’d be writing poems in class in college, listening to people talk and taking down language. It was always stolen time, and always a secret practice.

INTERVIEWER

What about the categories of fiction/nonfiction? It seems in your work that the two bleed into each other regularly. Are you writing yourself into your work? Are the poems in Evolution about Eileen Myles?

MYLES

I have all the information about Eileen Myles, so why not use what I’ve got. But I’m a fiction like everything else. I didn’t write my name, I didn’t choose my family. I could be writing and thinking I’m making something up and then I think, oh no, it’s actually true. I think I’m making a joke and then I think it’s actually the truest thing I’ve written in twenty-five pages. Genres are suspect and fiction and nonfiction — what’s the difference?

INTERVIEWER

To return to politics and poetry, what are your thoughts on protest poetry? Do you want to produce poems that are used in that way, or not?

MYLES

Well I do, I do. Again, adjectives like protest poetry always bug me. Poetry protests! When I came to New York in the 70s, it was right after a moment when people were writing poems protesting the Vietnam War. But when I got to New York, it seemed like a much more aestheticized moment. There was a lot of dismissal of feminist poetry. The world I was in was very experimental, New York School and Beat and Black Mountain and then proto Language was like, don’t go there and write work that’s about something. Honestly, I was very excited by the work that I was reading. There were women whose work was important to me but, by and large, I was reading guys and I was influenced by their work. A lot of the so-called feminist poets seemed more academic, a different aesthetic. I knew that I wanted to be where I was and so for me, my project then was to occupy what was essentially a white or sometimes black male aesthetic, with female context and a female body and female objections to those traditions. There’s a way in which my work was always inhabiting and protesting at the same time.

INTERVIEWER

Coming back to Evolution, I wanted to ask you about the poem “A Gift for You.” I love the images in this piece, humility as a “deflated/ beach ball/ on a tiny/ chair,” and “the calm/ person writing/ her calm poems” who “. . . opens/ her chest &/ a monkey/ god/ is taking/ a shit/ swinging/ on his/ thing.” There’s so much here, can you tell me a bit about this poem? Who’s the calm person, and what’s the monkey god doing in her chest?

MYLES

Sometimes, when I’m writing a poem, it’s like I’m dying. I’m so fucking calm, it’s like I’m marching to my own execution. I’m jittery, jittery, and then I get a line and I can feel that there’s so much behind that line. I start writing the poem and suddenly I’m in the spell. I write poems because nothing feels as good as writing poems, and so I’m the calm person writing her calm poem and a part of me is in there, a part of me is outside looking at that person, and suddenly I want to show my passionate burning insides and I want to be the monkey god and I want to upset you. I went to India in 1990, and for a time there was this monkey with the heart torn open over my desk. I haven’t seen it in years. As in filmmaking there are visual puns that get you from one scene to another and it’s like that deflated balloon sitting on the chair—it was auditioning for a poem though I did not know that!

INTERVIEWER

Who do you generally write for?

MYLES

Sometimes it’s just language and I’m just listing things and waiting for something to kick in. And sometimes I’m full of feeling and on some level it’s probably a message, though I may not know who the message is being directed to or when they will come into the poem. I think writing is talking to yourself, too. One of the last poems in the book has the line “I don’t even think my thoughts you do” because I know I’m infecting your brain with my thoughts. I’m unloading.

INTERVIEWER

Who are you reading today, which poets or writers do you find most interesting and important?

MYLES

I just finished Nightwood by DJuna Barnes, which I hadn’t read since my 20s or 30s. It’s such a masterpiece. I still think it’s one of the most perfect pieces of prose ever written. I’m reading poets like CA Conrad, Simon White, and Renee Gladman, who is a fiction writer who travels with poets. Her work is very important to me. My friend Adam Fitzgerald wrote a book called George Washington a few years ago. I’m reading a galley called Mother Winter by Sophia Shalmiyev. Leni Zumas’ Red Clocks was one of the exciting books recently. Andrea Lawlor’s Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl is an incredible novel. There’s so much amazing work right now.

INTERVIEWER

Back to Evolution, do you have a favorite poem in this book?

MYLES

“The Baby”:

The baby

says to the old

man let’s

have a cup

of coffee

the old

man says now

you’re talking.

Shoshana Olidort is a PhD Candidate in Comparative Literature at Stanford University. Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, the Chicago Tribune, the Times Literary Supplement and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2NRXJ7I

Comments

Post a Comment