Before he went to prison, Mark Loughney used watercolors and acrylics to create bright, playful portraits of his favorite musicians. His early work features Trey Anastasio and Grace Potter and Snoop Dogg, all smiling and content, deep into their guitars and joints. But then Loughney committed a crime that even now, years later, he can barely explain.

In 2012, when he was thirty-five and struggling to make it as an artist, Loughney got into a fight with residents of an apartment building. According to the police, he returned with a gasoline container and set the building on fire, sending multiple people to the hospital. It was big news in Dunmore, Pennsylvania, where Loughney was raised and where his father was serving a term as mayor. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to a minimum of ten years in prison. At sentencing, his lawyer brought up the role of alcohol. But Loughney still has difficulty comprehending his own actions. “It wasn’t as if I was in the midst of an addiction or dealing with clinical anger … It was a fight gone bad,” he wrote in a recent message from the State Correctional Institution at Dallas, thirty miles southwest of his hometown. “The main point I hope you can make for me is that I am very remorseful and contrite for what I did. I don’t often get the opportunity to express my remorse or apologies and I would really like to be able to do that in a public forum.”

After Loughney entered prison, his partner left him, and at times he felt catatonic. But listening to an interview with the Australian painter Johnny Romeo on the radio inspired him to return to his passion. “By the end of his interview, I was on my feet, in my cell, working,” he wrote. “I’m able now to actually understand how fragile and fleeting life is.” To make sense of his new surroundings, he began to draw what was around him, but instead of depicting the bars and razor wire, he focused on the people.

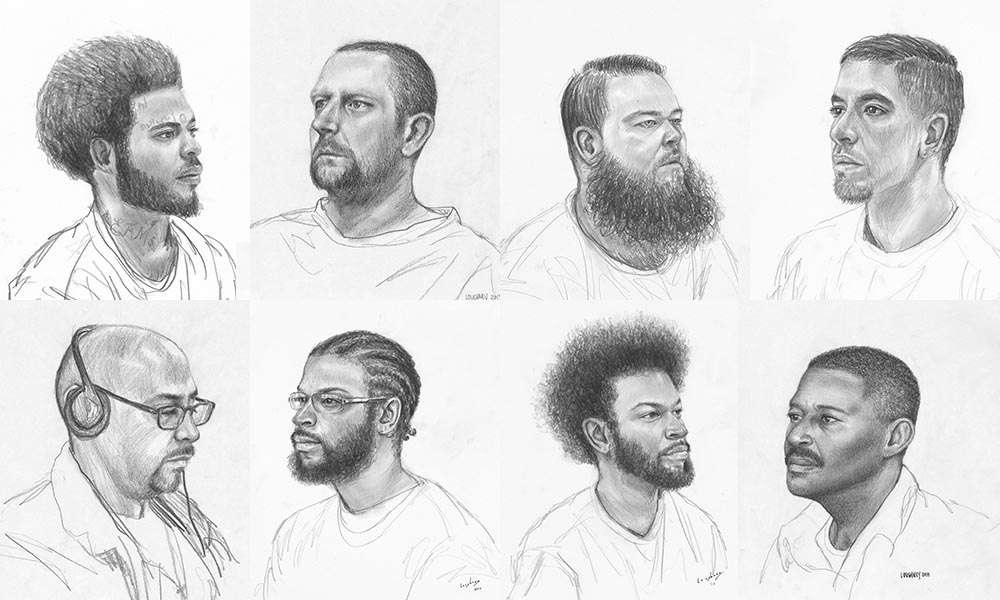

At first, his pencil-on-paper portraits of fellow prisoners were meant to be gifts they could give to their parents, wives, and children. The only criterion Loughney uses for choosing his subjects is their willingness to sit for twenty minutes “amidst the chaos of prison,” which is “harder than you’d think.” Eventually, Loughney realized that lining hundreds of the portraits up on a wall would make for a dramatic comment on politics and policy. The drawings were first shown last May at a gallery in Scranton, the city that adjoins Loughney’s hometown, under the title “Pyrrhic Defeat: A Visual Study of Mass Incarceration.” (The title is from the book The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Prison, by the scholars Jeffrey Reiman and Paul Leighton.)

Loughney asks viewers to donate to victims’ advocacy organizations and sends proceeds to them. “This is a way that I am able to put my feelings of remorse into a tangible form,” he writes.

He hopes the work will inspire people to reckon with the sheer number of people in U.S. prisons.

“The irony is that 500 faces is not even a drop in the bucket of our 2.4 million brothers, mothers, sisters, and fathers that are locked away in prisons in our country,” he writes. “The average man on the street probably has not the foggiest idea of what ‘mass incarceration’ means … so my hope is to just get the attention of at least a few.”

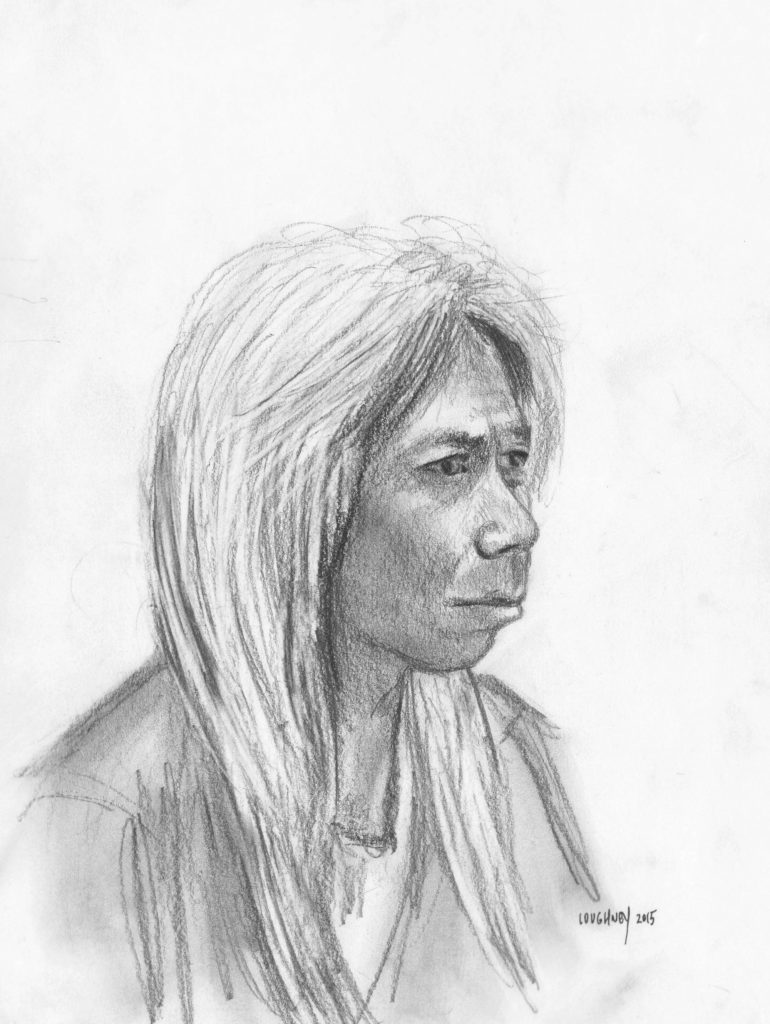

A few summers ago, Loughney kept noticing another prisoner on the yard: “An Asian man with striking long, white hair … he looked like a rock star from the ’80s.” They talked about the man’s love of drumming, and Loughney told him about drummers he liked. When Loughney finished the portrait, the man said, “Wow! You’ll make a million dollars!” He was from Laos and had escaped the country when his family was murdered. He was in prison for drug possession, and worried that his life would be in danger should he be deported. “Two weeks later, ICE came to get him,” Loughney recalled. He has since forgotten the man’s name.

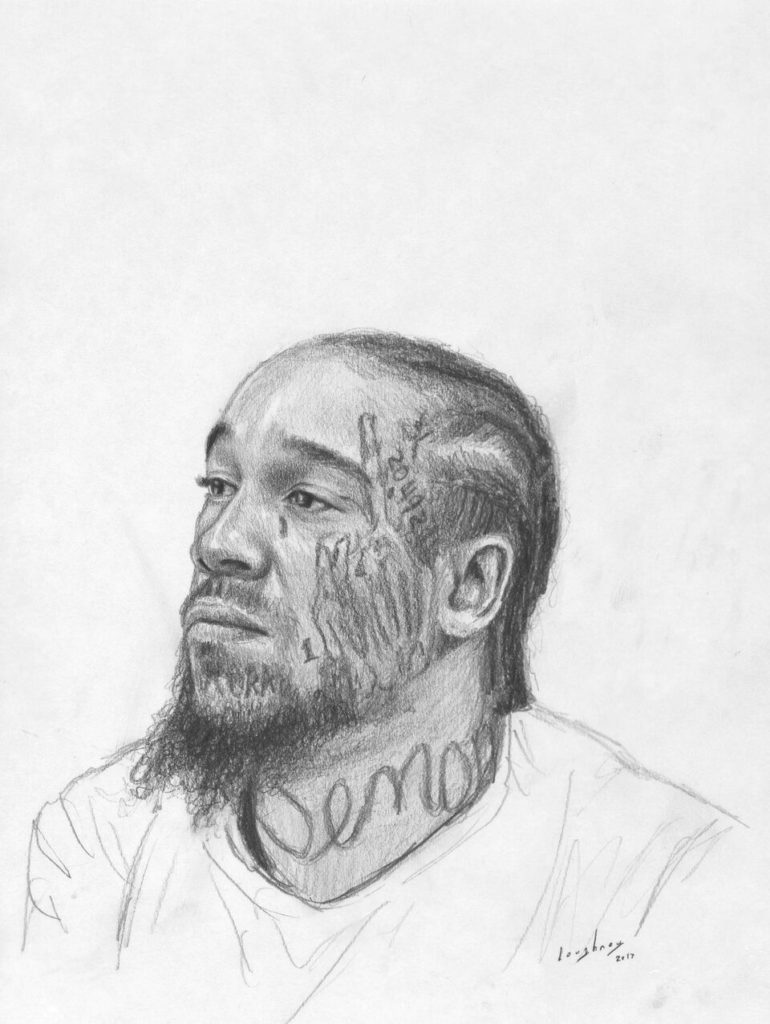

Loughney’s work brings him into contact with all sorts of prisoners he might not otherwise meet. “I saw a guy here with a skeletal middle finger tattoo that engulfed his entire face,” he wrote. “I said, ‘Dude, I gotta draw you.’ I asked him his name and he said, ‘Face.’ I asked him why people called him Face, and he replied, ‘It’s because I’m handsome.’”

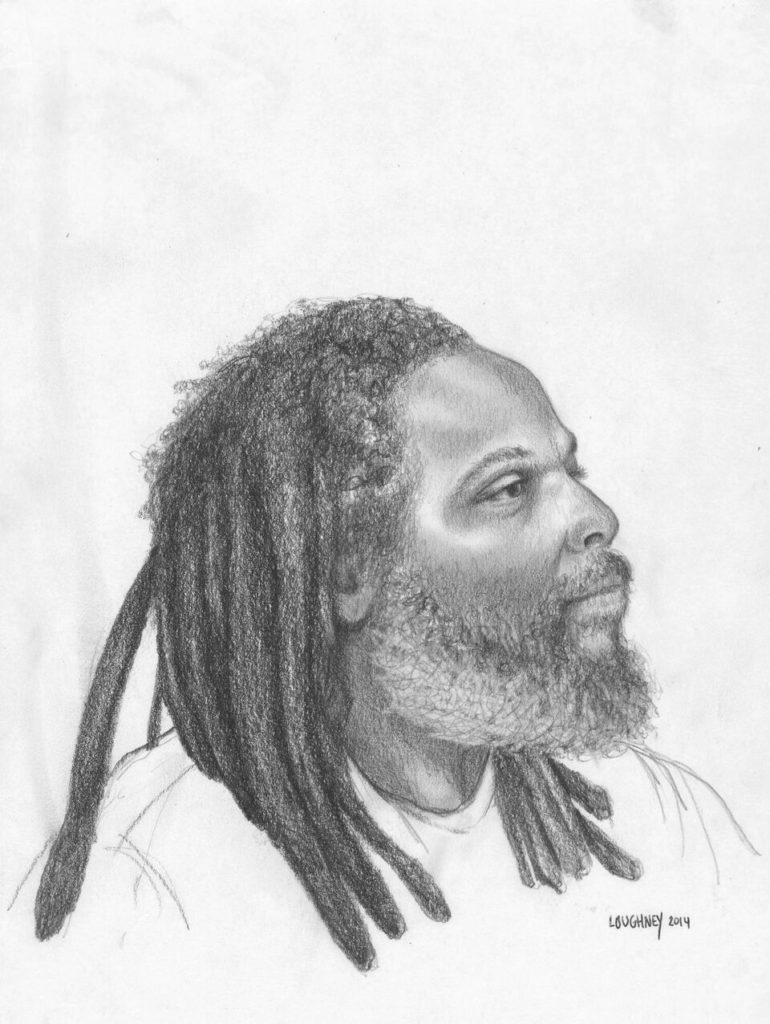

Loughney’s best-known subject is probably Phil Africa, who helped lead MOVE, a Philadelphia-based black liberation group, before being sentenced to more than thirty years for the fatal shooting of a police officer. As Loughney drew, a fly buzzed around them, occasionally landing on Africa’s face. “You could swat that fly if you want,” Loughney said. “No, he’s all right,” Africa responded. “He’s our brother, too.” Africa died soon after.

This story was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for their news

Maurice Chammah is a staff writer for The Marshall Project. His work has appeared in the New York Times, The Atlantic, and elsewhere.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2RrHAYL

Comments

Post a Comment