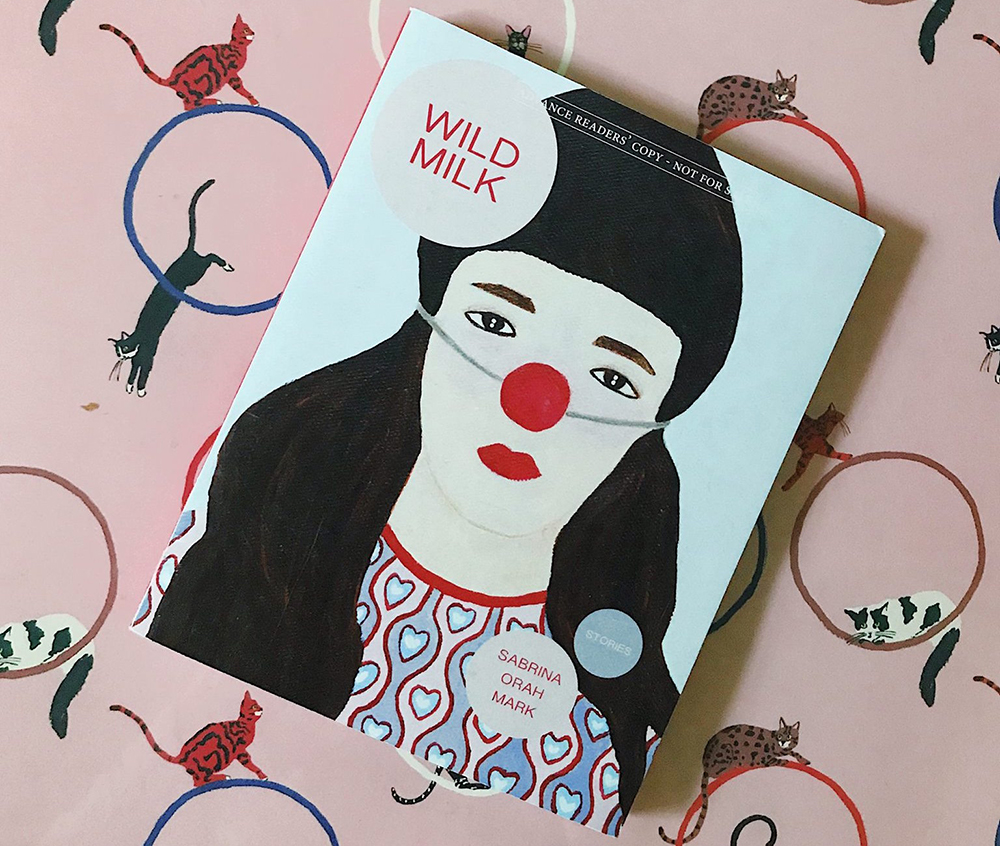

Sabrina Orah Mark’s Wild Milk, one of the duo of books released this year by the small press Dorothy, is a debut story collection that displays just how compelling surrealism can be, even almost a century after the movement itself had its debut. Mark is obviously a talent in the vein of Carrington, maintaining the strange dreamlike atmosphere of her fiction without losing its sense of substance, using skillfully interwoven images that create tight seams between each story. The slim, square little book, published just this week, is a retreat into the fantastic, poetic and playful—although every so often, much like in a dream, you catch sight of something you’re almost certain you recognize from waking life. —Lauren Kane

During a recent visit home to southwest Scotland, I was given a copy of Barefoot: The Collected Poems of Alastair Reid, edited by Tom Pow. Originally from Galloway, the itinerant Reid left Scotland for New York in his early twenties. He would call this city home for much of his life, and while the book doesn’t yet have an American publisher, countless other copies must have already trickled across the Atlantic. Some will have dropped through letter boxes; others will have been passed from hand to hand before dinner; one, surely, sits on a desk somewhere at his old employer, The New Yorker. I picture them, like Auden’s “ironic points of light,” dotted around the city, flashing out, exchanging their message. Other affirming flames burn all over the world, wherever Reid temporarily settled—be it Spain, the Dominican Republic, or his native Scotland. While Reid was perhaps better known for his translations, Barefoot focuses solely on his original poems. As such, there is a real impression here of having the poet to ourselves—a sense that as readers, we don’t have to share him. His voice can be stern, though it’s frequently balanced with a smile—you can almost hear it, sometimes, creeping in around Reid’s eyes. As such, it’s both a solemn and joyous collection. I particularly like him on faces—here are three of them: “Age has engraved his face. / Cradling his wagged-out chin, / I shave him, feeling bone / stretching the waxed skin” (“My Father, Dying”). “From wearing a face all this time, I am made aware /of the maps faces are, of the inside wear and tear. / I take to faces that have come far” (“Weathering”). “Here, one is grateful to the tolerant landscape, / and glad to be known by men with leather faces / who welcome anything but questions. / Words, like the water, must be used with care” (“New Hampshire”). —Robin Jones

Bruce LaBruce’s The Misandrists is as NSFW as you can expect a LaBruce movie to be. The plot is a satirical, timely update of Don Siegel’s The Beguiled (1971). The setting is an all-girls boarding school run by radical feminist nuns, where men are banned and lesbianism is (wo)mandatory. But there’s some trouble in paradise: one student smuggles an injured male comrade into the basement and makes love to him, and another is outed as an undercover police officer. Plus, the second-wave sisterhood isn’t equipped to handle a trans student. Big Mother (Susanne Sachße) declares, “Two cocks and one cop in the convent. This is not sustainable”—and promptly faints. The film is anything but cheap laughs, however; LaBruce knows his Frankfurt School. The convent’s internal squabbles are the conflicts that dog revolutionary discourse. LaBruce’s satire of radical feminism is affectionate, not polemical. When Big Mother performs a forced penectomy on her male captive, I didn’t agree with the method, but because of LaBruce’s humane filmmaking, I was still able to maintain some sympathy for her cause. In The Misandrists, you’re allowed to love Germaine Greer. This is a new Myra Breckinridge, but with Bruce’s satire instead of Gore Vidal’s smirk. This critique transcends itself and becomes aphrodisiacal. The film ends with a classic BLAB sequence, a pornographic coda that suggests the visionary, revolutionary potential behind the derided role of pornographer. Enough with the fear and division—wake up and smell the estrogen! —Ben Shields

I tried to write this pick last week, but I lacked the essential phrasing in Angela Flournoy’s profile of Barry Jenkins: “Much of the country, owing to our current political reality and Raoul Peck’s 2016 documentary, ‘I Am Not Your Negro,’ has recently become better acquainted with a truth black readers grasped long ago: James Baldwin was right about everything.” Earlier this month, I raced to read If Beale Street Could Talk before Jenkins’s film adaptation reached theaters on November 30. So good, so clear, so honest is Beale Street that I wonder how fiction is to surpass it. Ask me the best piece of contemporary fiction I’ve read in the last year—now I would say Beale Street. Ask me the best piece of classic fiction I’ve read in the past year—now I would say Beale Street. Existing perfectly as an essential work of its time and a timeless work of human truth and equally timeless American racism, Beale Street contains more compelling characters, more dynamic love of New York than you can find on any debut fiction shelf. How did I let thirty Mother’s Days pass without acknowledging Sharon Rivers? How did I hold tight the idea of friendship in romantic love before reading about the bond between Tish and Fonny? How did I dwell over scenes of family friction without reading and rereading the clash between the Hunts and the Rivers (fiction’s most satisfying use of the word cunt)? Baldwin, like the best of writers, knows as much about being a woman as he knows about being a man. “But that noisy, outward openness of men with each other,” Baldwin writes, “enables them to deal with the silence and secrecy of women, that silence and secrecy which contains the truth of a man, and releases it. I suppose that the root of the resentment—a resentment which hides a bottomless terror—has to do with the fact that a woman is tremendously controlled by what the man’s imagination makes of her—literally, hour by hour, day by day; so she becomes a woman. But a man exists in his own imagination, and can never be at the mercy of a woman’s.” Find a copy—you can. They are everywhere. There are many things wrong with this country, but at least we have Baldwin to tell us about it. —Julia Berick

This weekend I finished Heather Havrilesky’s collection How to Be a Person in the World, a book composed, in part, of pieces from her Ask Polly advice column at The Cut. The verdict is in: I consider myself forever changed, inspired to the core, suddenly, drastically, blissfully optimistic. I’m twenty-five, and it turns out I need a lot of advice. Reading this book made me realize that 1) I’m hiding behind a ”government-certified, grade-A, consumer-friendly woman,” 2) I’m punishing myself for being mortal, and 3) I deserve better, especially from myself. Havrilesky’s answers: “Fuck wondering if you’re lovable.” “Stop being grateful for scraps.” “Don’t lament and worry endlessly.” “It’s not over till it’s over, motherfuckers.” Her cutting humor and rousing advice helped me realize that I need to stop pretending I’m something I’m not and “tell tepid to fuck right off, Kanye-style.” She called me out, empathized with me, and then took me by the shoulders and shook me. “You MUST recognize that life among those who don’t appreciate or understand you is bullshit,” she writes. With vicious wit and merciless accuracy, she isolates motivations, redirects anxious and defeatist energy, and delivers specific, usually hilarious, instructions. This Monday, for the first time (ever?), I woke up at five A.M., drank my coffee, and exercised before going to work. I didn’t tell myself that I was lazy, useless, or running late again. I reminded myself that I don’t need to please everyone and that it’s okay to fuck up. I think it was the best Monday of my life. “The world has told you lies about how small you are. You will look back at this time and say, ‘I had it all, but I didn’t even know it. I was at the center, I could breathe in happiness, I could swim to the moon. I had everything I needed.’ ” Heather Havrilesky’s new book, What If This Were Enough?, came out this Tuesday. Once I have it, I will have everything I need. —Molly Livingston

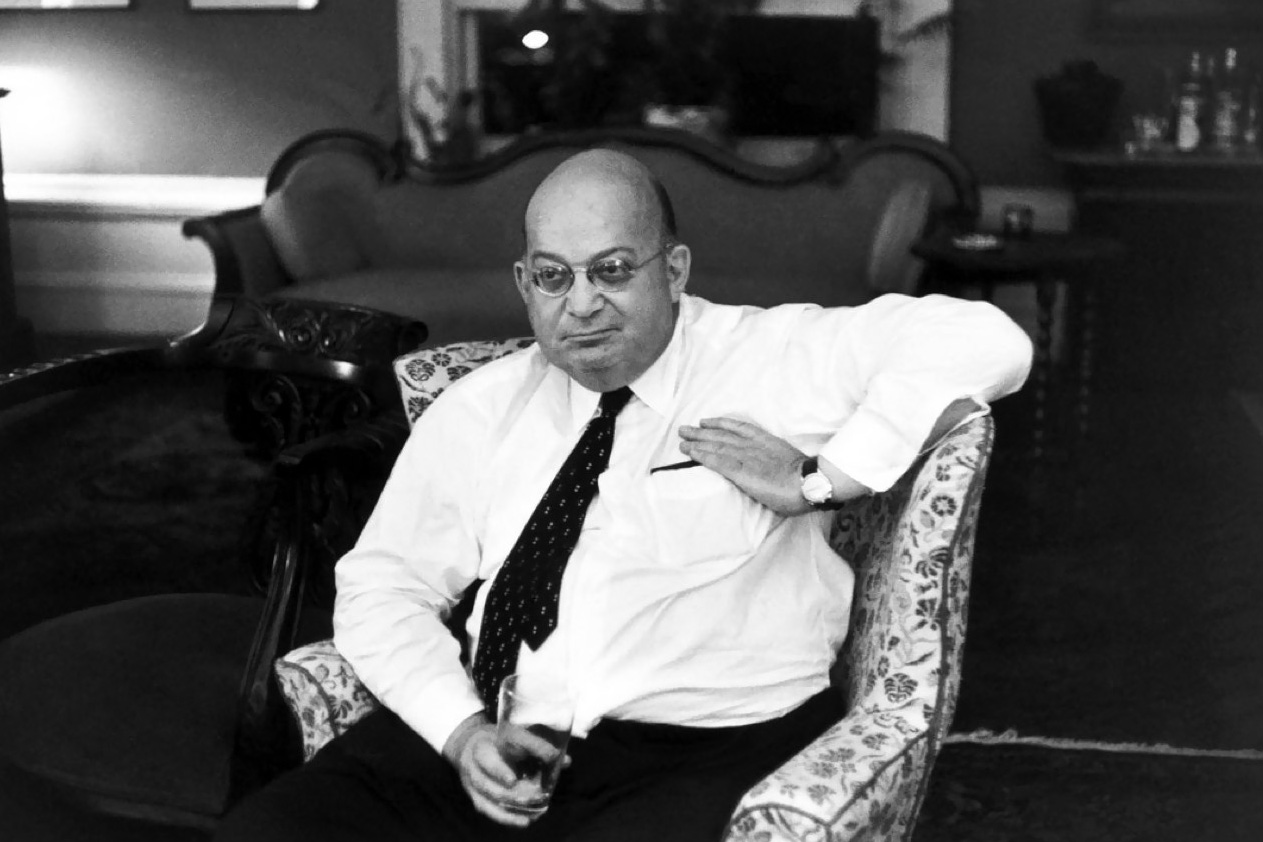

He had a bald head like a hard-boiled egg roughly peeled, surfaced with dimples, indentations, small flat protuberances like bits of clinging shell, his skin soft, infant, semi-pellucid. The sides of his head bulged over his low-slung ears, in parallel with his jowls, which fell in a wide-embracing arc from his cheeks, giving his face the hourglass silhouette of a cello. His chin was less an anatomical landmark than a lone sail sinking into the ocean—neck effaced by folds of skin, his head seemed a buoy bobbing on the undifferentiated mass of his torso. He had small, delicate hands, small feet prone to attacks of gout, and diffuse, wide-set eyes forever on the teetering verge of merriment. He was not attractive, he knew (his most cherished physical compliment came from a Parisian prostitute who deemed him “passable”), but in his own proud words “bald, overweight, and gluttonous”— proud because his corpulence was a warrant of his expertise, his experience, his philosophy, his sensibility. He was A. J. Liebling—New Yorker media critic, war correspondent, boxing aficionado, Francophile, and—as he demonstrates in his final work, the memoir Between Meals: An Appetite for Paris—a champion eater, someone with the rare gift for unalloyed pleasure. Between Meals is a temporally ranging elegy for eating and drinking in Paris, primarily devoted to his first, formative year in the city—1926, twenty-two years old, living on an allowance from his father, a successful immigrant furrier—while attending, or neglecting, medieval French literature classes at the Sorbonne. That year set his sensibility and instilled in him the soon to be out of fashion notion that pleasure is not a means but an end in itself of living. The body is not a sculpture to be perfected—Liebling is perfectly horrified at the emerging French interest in dieting—but an instrument to be used. As Liebling decrees at the open of the memoir, “The primary requisite for writing well about food is a good appetite.” One must first enjoy. Written in the last years of his life, his health failing, unable to travel or indulge as he once did, Between Meals itself is an indulgence, Liebling’s demonstration of appetite. As the beloved French Pot-au-feu is made of butchery leftovers—tough, inexpensive cuts and marrowbones—so is Liebling making a feast from the very last dregs of his meals, their memory. —Matt Levin

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2ygtsJ9

Comments

Post a Comment