When we read the collected letters of artists we admire, it tends to erode the marble busts we have chiseled of them like strange and abrasive weather. These are, in some ways, revealing documents—Elizabeth Hardwick suggested that in reading letters “we expect to find the charmer at his nap, slumped, open-mouthed, profoundly himself without thought for appearances.” But their disclosures are often merely aspirations in disguise. As a form, the letter encourages gentle self-mythology. Life submits to editing, and if days or weeks produce but one golden aperçu, the letter writer has grown used to treating time with voluptuous contempt. The jittery spontaneity of conversation is slowed down, encased within amber. A glacial, anticipatory pleasure reigns. Letters suggest a dream self, a living fiction, whether bustling and crowded with incident, or possessed of an indolent charm. These emanations that come to resemble their authors’ fears and fantasies make for incomplete but fascinating biography.

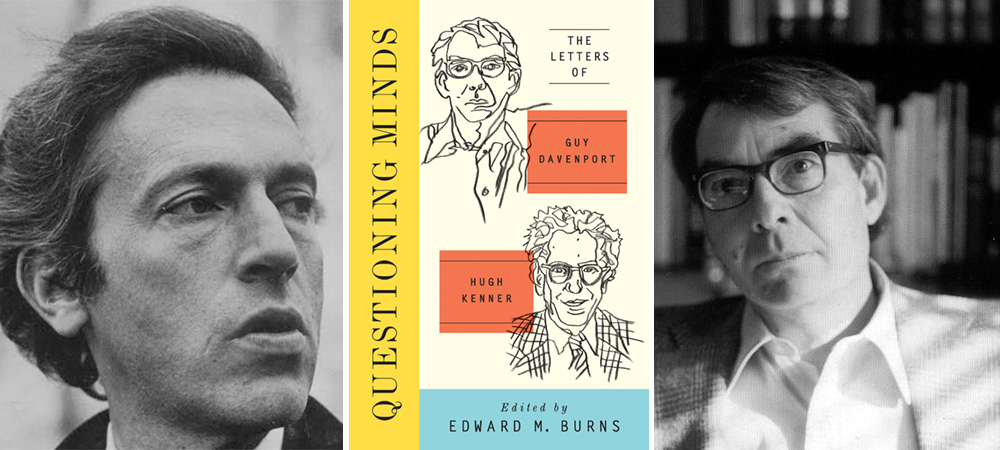

Though the form itself is vanishing, the pleasures afforded by reading literary correspondence have, if anything, intensified. Given the brittleness of the text message and the anxious sterility of email, there is a luxury to the epistolary rhythm: write—and wait. The fecundity of such a record has obvious appeal for scholars, who set out like lepidopterists, netting scandals, idées fixes, house guests, marital strife, disease, inspiration, signs of madness. The publication of a collection of letters pays the writer the compliment of such scrutiny. Questioning Minds, a gem of the form, was published this October by Counterpoint Press. It collects the voluminous correspondence—more than one thousand letters—between Hugh Kenner, modernist advocate and critic-savant, and Guy Davenport, literary collagist, essayist, and uncanny illustrator. It amounts to something like an intellectual love affair, replete with moments of courtship, seduction, devotion, and, eventually, betrayal. Given the polymathic depth of the correspondents, their associative flair and plasticity, and the sheer duration of their passionate exchange—nearly five decades, all told—we are unlikely to find a document of its like again.

“What is in the author’s mind so seldom gets on the page,” Kenner wrote to Davenport in 1958, early on in their letters—a shocking sentiment for a man about to embark on one of the lengthiest and most digressive correspondences of the twentieth century. (The collection is wonderfully, exhaustively annotated throughout by editor Edward Burns.) Kenner, then on the faculty at University of California, Santa Barbara, and Davenport, a nontenured lecturer at Haverford College, share ideas in a kind of ecstatic volley. Their friendship is at home in the dialectic; ideas are mere starting points, containers of iterative potential. From the great figures of literary modernism—James Joyce, T. S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, Samuel Beckett, Marianne Moore—to archival curiosa, Sapphic fragments, studies of motion, geodesic math, Walt Disney, Hellenic aesthetics, and the history of cinema (“I think Ulysses owes much to silent film,” Kenner wagers), Questioning Minds often reads like the almanac of a brilliant and eccentric family. Beneath the heat of their native curiosity, even the most arcane subjects achieve a sudden, flaring warmth.

Ezra Pound, whom both men idolized, exerts a pull over the correspondents like a collapsed star. Kenner and Davenport met in 1953 while presenting papers on the mercurial poet at Columbia University. That shared obsession animates their exchanges with a kinetic and gossipy energy. Sightings, rumors, and health scares abound. Pound, referred to as “Ez” or “EP”, haunts the letters without ever quite fully manifesting. The glimpses we’re offered are of a man in his dotage, puttering, cranky, made nearly transparent by time: “The news from Merano is that Ezra has quit writing, hope gone, Cantos unfinished, and is aging about 5 years a month,” Kenner laments. Later, while visiting the poet in Italy, Davenport provides this dispatch from a Rapallo beach: “Ez in long black drawers, something Tennyson might have worn in swimming … EP swam a while, floated a while. Bumped into one of the floating platforms gently.” The tone is protective, indulgent, lightly mocking though rarely less than affectionate. More than any other scholar, Kenner is responsible for the rehabilitation of Pound—without excusing his frankly terrible politics, he restored his standing as the central figure of literary modernism, il miglior fabbro of Eliot’s The Waste Land, the editor of Hemingway’s adjectives, the impresario of the literary avant-garde. Kenner’s masterpiece, The Pound Era (1971), is a gorgeous, knotty, unthinkably erudite reckoning with the poet’s work, “an X-ray moving picture of how our epoch was extricated from the fin de siècle.” For a Kenner fan, seeing the first intimations of the book’s “patterned integrities” come to life in the letters is pure, voyeuristic pleasure.

There is a similar satisfaction in following the collaborative efforts of the two writers, the fruit of which resulted in a pair of books, The Stoic Comedians: Flaubert, Joyce, and Beckett (1962), and The Counterfeiters: An Historical Comedy (1968). Both featured words by Kenner, and illustrations by Davenport, with drafts and sketches making their way from California to Pennsylvania and back, often accompanied with daring syntheses, marginalia, corrections, affirmations, and words of warm encouragement. Of his images, Davenport writes: “Nor wd I have slaved over ’em—and slave still—for anybody except you, all effort being to approach (hopelessly) the plastic goodness of your prose.” Kenner’s praise is usually briefer, though no less ardent: “You bury more good work than most of the best have published.” As in the greatest collaborative projects, the resulting work has a crackling, synchronous power. It is lucid and passionate criticism that avoids the abstruse literary theory of the sixties and seventies, gorgeously written at a line level—Kenner is a king of phrase making—and webbed with the filaments of ideas first broached in the letters.

The collection, though, is not merely a rich modernist inventory (even if, for some readers, this will happily be its main appeal). There are also instances of unlikely literary adventure and intrigue, what Burns in his introduction calls “Holmesian moments.” For example, there was the multiyear search for T. S. Eliot’s manuscript of The Waste Land, the coveted version marked with Pound’s influential edits. Tipped off by Pound’s estranged wife, Dorothy, Kenner and Davenport believed the secretary of the famous collector John Quinn, a woman named Jeanne Robert Foster, might have information. “J. Foster, by the way, has ‘deposited’ her Quinn papers in Houghton, so that to find out what ‘the Eliot MS’ might be, without letting [librarian William Jackson] know that I was snooping, I had to send a spy.” Though they never discover the elusive manuscript, the passion with which they pursue it is worthy of a crime novel.

More terrestrial difficulties are stitched through their intellectual banter like black thread: the death of Kenner’s first wife, Mary; the death of Davenport’s father; professional anxieties and health concerns; flaccid book sales. As is often the case with friendships, there is no final break-up. Instead, there is a slow fraying of ties. “We, you and I, are beginning to drift out of synchronicity,” Davenport wrote to Kenner in 1977. While neither ever offers a reason for this cooling, Burns suggests that it may have been due to Kenner’s disapproval of Davenport’s sexual relationships with men. We watch their correspondence dwindle to a handful of missives in the nineties, mainly holiday greetings written by Kenner’s second wife, Mary-Anne. There is only one letter in 2000, and an additional short letter—it was to be the last—in 2002, roughly a year before Kenner’s death. “We’ve been separated too long,” Kenner writes. And then: “Are you still nontech, or have you by any chance an email address by now?”

A Kenner and Davenport email thread? After one thousand letters, it is difficult to imagine. Still, perhaps the form is finally inconsequential, given the caliber of the minds. Like any intellectual exchange, the letters of gifted writers become an atlas of their intricate subjectivity. “Thought is a labyrinth,” Davenport wrote to Kenner in 1963, a phrase he was much struck by. Eight years later, Kenner would end The Pound Era with those very same words. It was the greatest compliment he could have bestowed upon his friend: that his wisdom should leap from the surface of these treasured letters and their thoughts be permanently conjoined.

Read Guy Davenport’s Art of Fiction interview.

Dustin Illingworth is a writer in Southern California. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, the Times Literary Supplement, and the Los Angeles Times.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2RU8Oqp

Comments

Post a Comment