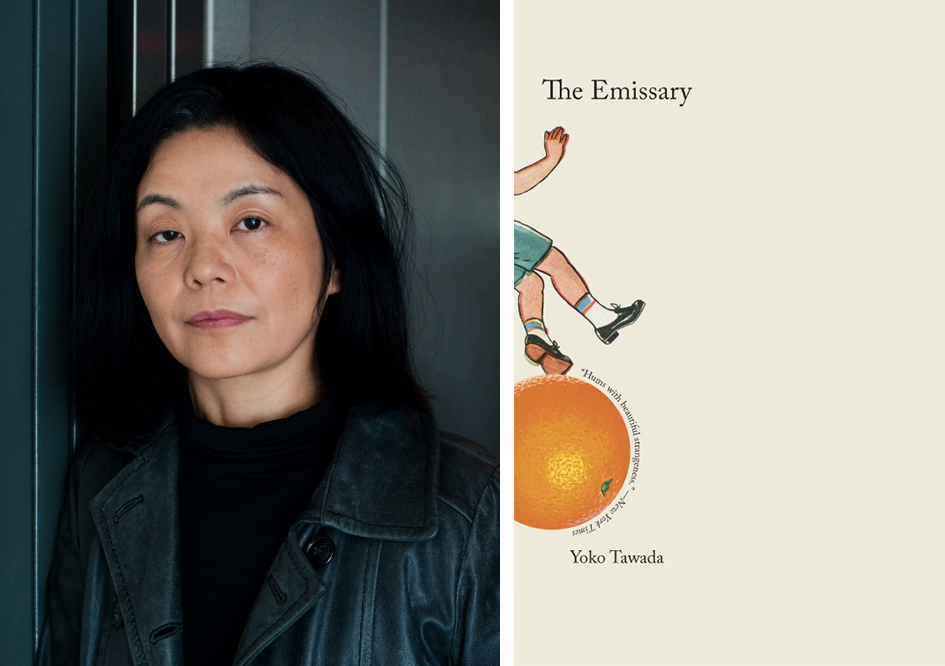

Yoko Tawada (b. 1960), who writes in Japanese and German and has been translated around the world, studied Russian literature in Tokyo before hotfooting it to Hamburg: “Russian writing was just the greatest, but I couldn’t study in the Soviet Union for political reasons, so I got a job in Hamburg.” She settled in Berlin, and has now published numerous novels, plays, poems, and essays. Her latest novel, The Emissary (translated by Margaret Mitsutani), won the inaugural National Book Award for translated literature this week.

Among the finest of Tawada’s works are short stories about adapting to new cultures, both physically and linguistically. The daughter of a nonfiction translator and academic bookseller, Tawada learned to read in over five languages; she speaks English, but doesn’t write it. “I feel in between two languages, and that’s big enough,” she told me. Her stories often turn on feeling outside the culture, as an immigrant, as a citizen witnessing great national change, or even as a tourist.

In between collecting several other prizes, including the Akutagawa Prize, the Kleist Prize, and the Goethe Medal, Tawada has fashioned the dream bohemian existence for herself in Berlin, writing forewords and books and collaborating with the likes of Wim Wenders and Ulrike Ottinger.

When we met at Denmark’s Louisiana Literature Festival this past summer, I made it a personal mission to ask Tawada polar bear questions she hadn’t heard before. Tawada, who has a long-standing interest in the Cold War and socialism, based the protagonist of her best-selling Memoirs of a Polar Bear on the Berlin Zoo’s star resident, Knut, who was born and raised in captivity, and died in captivity as well. “Danish sounds quite polar-bear-ish,” the author said. Tawada peppers her speech with German phrases and portmanteaus. She is cheeky, full of light, and modestly, sagaciously witty.

INTERVIEWER

When do you write?

TAWADA

I look like a person who cannot think when I wake up, because I’m still quite between the sleep and the dream and the waking, and that’s the best time for business.

INTERVIEWER

Of the three bears’ stories in Memoirs of a Polar Bear, which was the most challenging to write? Did you feel a deeper responsibility, emotionally, to any one of the three?

TAWADA

The first bear [Knut’s grandmother, a dancer turned author fleeing Soviet Russia], perhaps. And Knut was in my mind with each of them, naturally, but I am not Knut.

INTERVIEWER

You’re not?

TAWADA

I’m not Knut! The second bear is also okay … and there it was most difficult to measure the historical facts, to research.

INTERVIEWER

I noticed the way you switch, in the book, between the words paw and hand.

TAWADA

Yes, it’s a story about human and animal rights. The circus was important for the socialists, it demonstrated a control of nature. In the Middle Ages, court cases were brought against animals. Essentially, though, Memoirs is a novel about writing, and it’s inspired by Kafka, Heinrich Heine, Bruno Schulz. On a symbolic level, the Cold War is what drives the bears. Snow is so important, not warmth or the sun. Winter is a time when we are thinking more deeply.

INTERVIEWER

Do you feel that writing for you, as a multilinguist, is an anarchic act?

TAWADA

Being multilingual is tricky. I feel more as though I am between two languages, and that feels like enough. To study that in-between space has given me so much poetry. I don’t feel like one of those international people who juggles many tongues.

INTERVIEWER

Do you spend much time in nature?

TAWADA

German people often go to the forest, and I like it, too. In Tokyo, they don’t have the forest, so people have bonsai trees as their computer wallpaper and go “forest bathing” via their screens. I must say, I prefer Norway’s forests and landscapes. For meditative reasons I love to do Tai Chi in Berlin.

INTERVIEWER

In The Emissary, Japan isolates itself from the world after a disaster. Children become frail, and the elderly are the only ones with real agency. Yoshiro witnesses the decay of his great-grandson. You write, “When he had seen Mumei’s baby teeth drop out one after another like pomegranate pulp, leaving his mouth smeared like blood, Yoshiro had been so distressed he’d wandered aimlessly around the house for a while.” He also has a close relationship with his knife. “When he grasped the handle, a second heart began to beat in Yoshiro’s hand.” Why this violent imagery?

TAWADA

The Japanese knife is just so very good. The idea is about quitting the industry of cars and modern electrical appliances and going back to the things Japan produces very well.

INTERVIEWER

In The Emissary it’s the older generation who must keep the frail, younger generation alive. How did this idea come to you?

TAWADA

On top of the aging population in Japan, there was the Fukushima disaster. The old people did not become sick from nuclear poisoning, but small children did. Some of the elderly claim they are impervious to it. It’s also a story about the isolation of Japan following national disasters.

INTERVIEWER

Japan does seem to be a modern, advanced country, and yet it is hit by natural and chemical disasters like no other.

TAWADA

And there’s an island mentality still, even after the event. That people must stay in the damaged territory and rebuild it. People in Europe are different. People fled Chernobyl.

INTERVIEWER

The Japanese sensibility of staying with the pain and learning, rather than abandoning: that seems slightly masochistic, but also Shintoist?

TAWADA

Absolutely. It comes from history: it was always better to stay than to leave. To stay independent and to remain connected to the ancient. In the fictional world of The Emissary, new public holidays are declared. I’ve always liked the sound of the Day of the Ocean [created in 1941 to commemorate the Meiji emperor and his 1876 voyage in the Meiji Maru] and Day of the Mountain [inaugurated December 11, 2016], et cetera, but in reality, because most of them were created under the former emperor, I don’t like them. It’s the government’s way of getting around the law that forbids tying politics with religion. The Japanese cannot, for example, celebrate the emperor’s birthday with a holiday. That’s Shintoism. Instead they have something like Ocean Day. Much like in East Germany.

INTERVIEWER

There’s a sense of nostalgia in the book. Yoshiro yearns for the simple days of yesteryear. “This was how Yoshiro wanted to live: shedding not blood, not tears, but a steady stream of juice.” Do you feel that your student days in early-eighties Germany—a relatively free-spirited, happy time, by all accounts—laid the foundations for the novels you’ve produced in recent years?

TAWADA

Everything began for me in Hamburg in the eighties. It was like nowhere else, you could just go in and out of any classes you liked. It opened up my learning and my reading. In my early Russian-literature days, Dostoyevsky became a sickness, an addiction for me. Then came Walter Benjamin, Edgar Allan Poe, Gertrude Stein, and Jorge Luis Borges.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think people still run away to Berlin, and if so, why?

TAWADA

The city is unlike anywhere else. It’s like a big artist’s project. Writers, artists, performances, concerts, lectures, constantly. It’s a stage and not a city.

Alexandra Pereira is a British writer whose work has appeared in Playboy, Vice, Condé Nast Traveler, and Stride. She is an editor at Pariah Press and lives in Copenhagen.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2DHjZ2N

Comments

Post a Comment