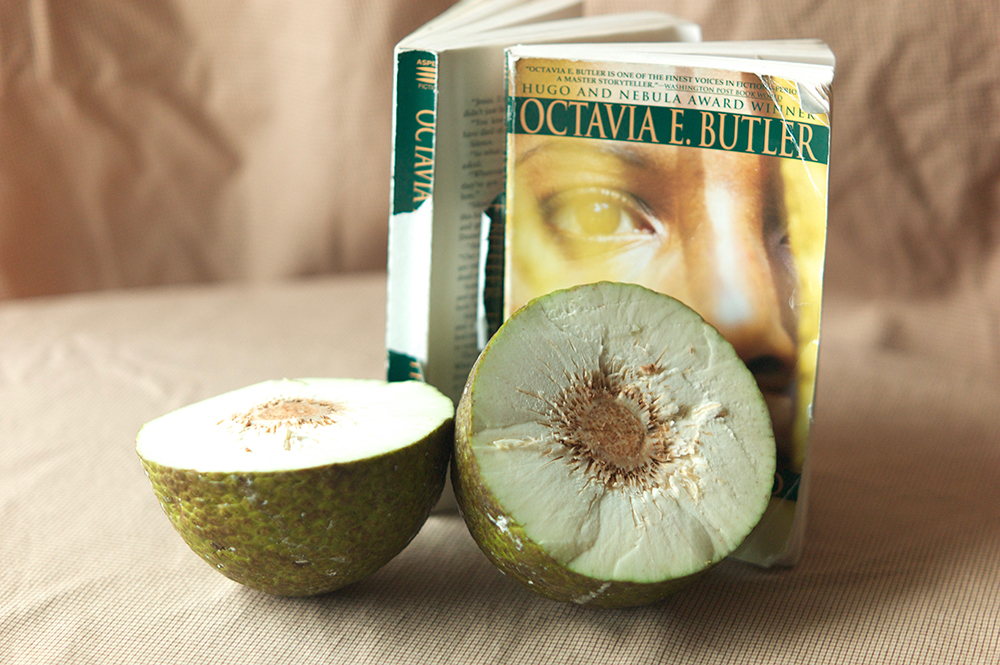

My copy of Lilith’s Brood, with a breadfruit, soon to be made into an edible bowl. I’ve read the book six times, as the damage to my copy shows.

The most perfect alien abduction scene in all of literature occurs in Dawn, the first volume of Octavia Butler’s Imago trilogy. Butler (1947–2006) was a rarity, a black woman publishing science fiction in the eighties, and the Imago trilogy is her masterpiece. On the first page, the protagonist, Lilith Iyapo, comes to consciousness with the words “Alive! Still alive. Alive … again.” She finds herself in a familiar room with “light-colored—white or gray, perhaps” walls and anonymous touches like a bed that’s “a solid platform that gave slightly to the touch and that seemed to grow from the floor.” Lilith has been here before, has undergone weeks or maybe years of questioning by disembodied voices that come from the ceiling, has lost her mind and fallen asleep or lost consciousness only to reawaken and be put through it all again. This time, there’s food—“the usual lumpy cereal or stew, of no recognizable flavor, contained in an edible bowl that would disintegrate if she emptied it and did not eat it”—and something new: clothing. She dresses and eats. She is finally ready to cooperate with her unknown captors.

Lilith’s last memories from before the locked room are of an all-annihilating nuclear war, of which she recalls, “a handful of people tried to commit humanicide.” Despite the strange circumstances of her captivity, she doesn’t realize she’s on a spaceship in the hands of aliens until the first one comes through her door. She then discovers a race of humanoids called Oankali, who are covered with shaggy, grotesque, tiny “sensory organ” tentacles. The Oankali long ago scooped up all survivors of the war and have been keeping them in suspended animation while restoring the earth to a primordial, habitable state. Now they’re ready to repatriate the survivors—but only under certain conditions. Lilith has been chosen to help the Oankali manage her fellow humans.

That Lilith doesn’t want to be a collaborator is the first problem. The second is that the aliens cause a visceral, bone-deep, skin-crawling horror in human beings—a sensation akin to being confronted with giant hairy bugs. And the third is that the Oankali want to have sex. More than that, they are gene traders, and they offer humanity a future only if the survivors are willing to give up human children and breed a new third race, to be left behind on earth when the spaceship moves on.

The plot plays out on the repatriated earth and builds from the drama and morality of making this choice. Some people, including Lilith, cooperate with the aliens. Some resist. Alien tentacle sex happens in five-person kin groups through a third-gender person called an “ooloi,” and the act turns out to be addictively pleasurable, which complicates matters. The losses—no human children, no traditional sexual relationships—are real and threaten the characters’ deepest sense of their humanity.

Apples get boiled with salt cod to make a stuffing for the breadfruit, a surprisingly successful dish.

I’m occasionally asked what my favorite book is, and I never know how to answer. Should I choose the book that’s most perfect as a work of art? The one that has the most socially meaningful message? The one I’ve most enjoyed reading, or have read the most times? The Imago trilogy, sometimes published in a single volume as Lilith’s Brood, is none of those, but it’s my pick.

I think the Imago trilogy is my favorite not because favorites are both critical and aesthetic pleasures—though Butler is a superb writer whose work easily transcends genre—but because it involves wish fulfillment. True favorites are worlds we want to inhabit, adventures we wish to have. I’ve always been interested in the line between pleasure and disgust (fans of horror movies or amateur pornography might know what I mean), which is just the territory this particular adventure inhabits. The characters’ battle to accept the aliens in their midst, to try something really weird, to love people with tentacles and bear their alien children is intriguing, in an exhilarating, confront-your-fears way. My intuition that my choice of the Imago trilogy was about wish fulfillment was confirmed by my total glee at the thought of making and eating food from the books.

I wanted to make food that seemed appealing but also a little wrong, in the spirit of the book, like this vegan coconut cream pie with a “crust” of roasted sweet potato.

From that first bowl of porridge, what the characters eat is an issue. The Oankali, while cruel in some ways, are basically presented as an advanced, peaceful, enlightened race living as a collective. They’re vegetarians, and they teach the formerly civilized, urban-dwelling humans to farm on their rejuvenated version of earth, growing and harvesting familiar, human standbys like rice, beans, nuts, coconuts, yams, breadfruit, pineapple, corn, plantains, a “melon with sweet orange flesh,” and “cassava bread with honey,” as well as new things like “scigee,” which “the Oankali had made from some war-mutated Earth plant. Humans said it had the taste and texture of the flesh of an extinct animal—the pig.” There’s also “inga,” “bean pods that provided an almost candy-sweet pulp.” There are no large animals. Some humans eat small animals or fish, which the Oankali find puzzling but allow in order for the people to still feel human.

I began with recipes incorporating ingredients with this profile, from a book my husband bought on a Caribbean vacation, Traditional Jamaican Cookery by Norma Benghiat, though the mandate that the bowls all be edible took me far beyond its pages. The simplest dish I made was rice and beans, which the characters specifically eat in the book. Mine was Jamaican-style, and I served it on a beautiful, raw cabbage leaf. Breadfruit is probably the food most mentioned in the novel, and amazingly, the Jamaican cookbook has a recipe that makes an edible bowl from a roasted breadfruit and stuffs it with salt cod. I also experimented with making versions of some of the pies found in the cookbook, staying faithful to the Imago trilogy’s limitations (no wheat or oats, no animal products). One is a coconut cream pie; I made mine vegan, with a “crust” of roasted sweet potatoes. Another is guava; mine uses the flavor profile but space-ages it up with a crust of sweet-potato flour (a specialty ingredient I ordered online) and coconut oil. Lastly, I used cassava for the porridge from the book’s first pages and made an edible bowl from cassava flour to serve it in—an idea entirely of my own invention.

I tried to make a piecrust with sweet-potato flour and coconut oil. Although it came together well in my hands, it fell apart instead of rolling out.

Interacting with so many unfamiliar ingredients was thrilling. To make the coconut cream pie, I needed several things to go right: to roast the potatoes correctly, make a coconut-milk pudding that would set, and get coconut cream to whip up fluffy for the topping. The first two steps worked after some trial and error, but I couldn’t get the coconut cream to whip—it needs to be cold to get the volume, but when cold, some elements turn too solid for the mixer—so I substituted whipped cream at the last minute. The results would probably be considered a good dessert under primitive conditions. For the second pie, the sweet-potato flour was very light and airy and had the slightly disturbing aroma of a health-food store from back before they were fashionable. The dough I made from it was impossible to roll out, even when it was well chilled, so I turned the pie into a crumble, which I served dusted with cocoa powder. I’m not sure if chocolate and guava is a known flavor profile, but it was wonderful. Both desserts were weird but appealing in just the way I was hoping.

The dish truly worthy of the Oankali, however, is the stuffed breadfruit. I had been seeing breadfruit in my grocery store, peeled and cut into chunks, but when the day came to cook, none was available. I finally tracked one down in a specialty West Indian grocery store in Queens and sent my husband to pick it up. He returned with two large, scaly, and underripe items—the best we could do. The Jamaican cookbook’s instructions on roasting them did not work (whole, for thirty to forty-five minutes, in an oven set to three hundred fifty degrees). I cut ours in half, smeared them with coconut oil, and put them in the oven at four hundred degrees for forty minutes, until the fruit looked soft enough to eat but not so soft it would fall apart when peeled and carved into a dish. Roasted, it had a fishy, sour aroma. When I cored it, I found a fascinating perforated texture that was both beautiful and a little creepy.

Things were going well, I thought, but then I looked (way too late) at my salt-cod stuffing recipe and realized that eighty percent of its volume is dependent on a Jamaican fruit called ackee—available only in cans, needing to be cleaned of a poisonous membrane, and, in any case, available no closer than Queens. The Internet told me that ackee’s unique flavor isn’t replicable with other fruits but that the closest comparison is apples. Like an Oankali gene trader building a third species, I boldly substituted sliced apples for ackee and threw them in a pan with the salt cod, a diced Jamaican red pepper (seeds and all), a tomato, thyme, and hazelnut oil. The cod reeked even more than the breadfruit, but the apples turned the mixture a beautiful shade of rosy blush. I was almost afraid to try the assembled dish, but when I did, I was amazed by the blazing sweet-salty-hot flavors. It was truly delicious.

Finally, I made the porridge from the opening scene. A cassava is the same thing as a yuca (but not the same as a yucca), a white-fleshed tuber with a waxy brown coating and a hairy central spine. To be used for anything, it must first be made into a “flour” by despining it, grating it, squeezing it of its juice, and drying it out. (The Internet implies that the juice is poisonous; I tasted it several times before I realized that, and I’m still alive.) My recipe says the drying process takes twenty-four hours, which might be true in the tropics, but under Brooklyn’s winter conditions, I think one would ideally want three days. My recipe also says the grated mass could be dried out in an oven set at a low temperature. My oven’s lowest temperature is two hundred, and at that heat, even with the door open, the lumps of grated cassava cooked almost immediately. Days of painstaking fluffing and air-drying on trays eventually produced the ideal meal: light, flaky. At first, I was frustrated by the slow process, but turning and fluffing the grated cassava became meditative and somewhat pleasant.

Alone, the cassava meal has a mild sweetness that is nearly tasteless. When cooked in milk with a dusting of nutmeg and a drop of honey, it is bland, yes, but nearly magical in its simplicity. The bowl is even better. Cassava bread is a one-ingredient dish. You make a patty of the meal and fry it in a skillet; its glutinous properties make it stick together and toast. I took my breads off the griddle while they were still flexible and stuffed them into muffin cups, then dried them out in an oven on low heat. They were tinier than I would have liked, lacy and extremely fragile, but they held porridge. Eating the bowl together with the contents was crispy, flaky, and creamy, much better than what the aliens served Lilith but exactly what my favorite books deserved.

Cassava Porridge in a Cassava Bowl

(Adapted from Traditional Jamaican Cookery, by Norma Benghiat.)

For the cassava meal:

2 cassavas

This process takes at least forty-eight hours and makes about four cups of meal. Peel and quarter the cassavas, removing the hairy spine from the center. Grate on the fine side of a box grater. Squeeze out as much liquid as possible with your hands. At this point, you’ll have nearly hard chunks of squeezed pulp, which need to be dried and turned into meal. Break the chunks up with your hands as much as possible, then spread on a tray to air-dry. Return every few hours to rub the chunks between the tips of your fingers, breaking up further, and again spread out evenly on the tray. When dry, the meal should resemble crumbly grated parmesan cheese.

For the bowl:

2 cups cassava meal

Preheat the oven to 350. Set out a muffin tin. To make the cassava bread, heat a dry skillet to medium-hot. Add a quarter cup of cassava meal, all in a heaping pile, and spread gently but quickly with a fork until you have a roughly four-inch round. Fry until the edges are golden and the bread has turned glutinous enough to hold together but is still flexible. Flip, and cook the second side for about a minute. Remove and tuck into the muffin tin. If the bread breaks, you’ve fried it for too long. Repeat until the meal is gone and the muffin tin is nearly full. Bake for seven to ten minutes, until the bowls are golden and completely crisp.

For the porridge:

2/3 cup cassava meal

2 cups milk

1/4 tsp nutmeg

honey for drizzling

Bring the milk to a boil, and immediately remove from heat. Stir in the cassava meal, return the pan to the heat, and simmer until thickened, about five minutes. Add the nutmeg.

To assemble:

Put a dollop of porridge in each bowl, and top each with a drizzle of honey. Serve immediately.

Rice and Beans

(Adapted from Traditional Jamaican Cookery, by Norma Benghiat.)

1 cup dried kidney or other beans

1 can coconut cream

6 cups water

2 tsp fresh thyme leaves

1 Jamaican hot pepper, whole

2 cloves garlic, minced

1/2 tsp ground allspice

1 tsp black pepper

1 1/2 tsp kosher salt

1 tsp brown sugar

2 1/4 cups long-grain brown rice

Soak the beans overnight. Drain.

Combine the water and coconut cream in a large saucepan with a lid, add the beans, and bring to a boil. Turn down to a simmer, and cook until the beans are nearly tender, an hour to an hour and a half.

Add the thyme, hot pepper, garlic, allspice, black pepper, salt, brown sugar, and uncooked rice. Check the level of liquid over the rice; there should be at least an inch. If there’s not, add more water. Bring to a simmer, and cook, covered, for twenty to thirty minutes, until the rice is tender.

Breadfruit Stuffed with Salt Cod and Apples

(Adapted from Traditional Jamaican Cookery, by Norma Benghiat. Serves two.)

1 breadfruit

2 tsp coconut oil

1 red apple, sliced

1/4 lb salt cod

2 tbs hazelnut oil

1 onion, sliced

1 sprig thyme, plus more for garnish

1 Jamaican red pepper, diced

1 small tomato, chopped

black pepper

Preheat the oven to 400. Cut the breadfruit in half through the shorter cross section, rub with coconut oil, and roast, until slightly softened but still firm enough to carve. (The length of time in the oven will really depend on how ripe the breadfruit is; mine was not very ripe and took forty minutes.) When the breadfruit is roasted and cooled, cut off the bottom so it sits flat, then peel. Carve out the center to create a sort of bowl.

Bring a medium saucepan of water to boil. Add the cod and the sliced apple, turn the heat down to medium, and boil until the apple is soft. Drain. Separate the cod and flake it, removing any skin or bones.

Put a frying pan on medium-high. Add the hazelnut oil, onion, thyme, hot pepper, and tomato. Sauté until the onion is softening and beginning to brown. Add the apples and fish, toss to combine, and season with plenty of fresh-ground black pepper.

Fill the two breadfruit halves with the filling, garnish with a sprig of thyme, and serve.

Coconut Cream Pie with Roasted Sweet-Potato Crust

(This recipe was adapted from Minimalist Baker.)

For the crust:

1 large sweet potato

1 tbs coconut oil, solid state

2 tbs coconut oil, melted

1/4 tsp salt

Preheat the oven to 400. Grease a nine-inch pie plate with the solid-state coconut oil. Mandolin the sweet potato in quarter-inch slices. Toss the sweet-potato slices in the salt and melted oil, then arrange them in the pie plate, making sure they overlap as much as possible and leaving no gaps. Press tinfoil tightly over the crust, and bake at 400 for thirty minutes. Then uncover and bake fifteen to thirty more minutes, until the potato is completely soft and creamy but not starting to brown. Remove, and cool completely.

For the coconut cream filling:

1/4 cup cornstarch

1/3 cup sugar

1 pinch sea salt

1 can light coconut milk

1 tsp vanilla extract

1/2 cup shredded coconut

Add the cornstarch, sugar, and salt to a small saucepan. Stir in the coconut milk, whisking to avoid lumps. Place over medium heat, and cook until bubbling. Whisk frequently. Reduce heat to low, and cook for five minutes, stirring constantly with a rubber spatula, until the pudding is jiggly and runs off the spoon in a thick ribbon. Stir in the vanilla extract and shredded coconut. Refrigerate until cooled and set.

For the topping:

2 cups heavy cream

2 tbs sugar

1/2 cup coconut flakes, toasted

Whisk the cream until fluffy. Add sugar, and stir to combine.

To assemble:

Spread the coconut pudding in the cooled pie shell. Top with whipped cream, sprinkle with toasted coconut flakes, and refrigerate until ready to serve.

Guava Crumble with Cocoa and Yam Flour

For the crumble:

2 cups yam flour

1 tbs cocoa powder

2 tbs sugar

1 tsp salt

3/4 cup coconut oil

powdered sugar, to dust

cocoa powder, to dust

Combine the yam flour, cocoa powder, sugar, and salt in a medium bowl. Rub in the coconut oil until the mixture is clumpy.

For the filling:

8 cups guava, peeled, cored, and sliced

1 tbs cornstarch

1 cup sugar

1/2 tsp cardamom

Combine filling ingredients, and let macerate for fifteen minutes.

To assemble:

Preheat the oven to 400. Line a baking sheet with tinfoil, in case of spills. Fill a pie plate or baking dish with the filling, then add the crumble topping. Cover with tinfoil (the sweet-potato flour browns quickly), set on the tinfoil-topped baking sheet, and cook in the oven for an hour and fifteen minutes, until the fruit is soft. Remove the top tinfoil at the end to brown the topping, if necessary. Dust with powdered sugar and more cocoa powder, then serve.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2FSYnSX

Comments

Post a Comment