Edmond Baudoin is a force of nature who holds a singular position in the French comics scene. An ink-stained Proust, his drawings and his memory keep bringing him back to the small, Southern French village of his youth as well as the nearby city of Nice, on the Mediterranean coast. In many of his books, you see the same woodland paths, the same barren views of Nice harbor, the same faces: his own adolescent self, his parents, his brother.

He came to cartooning relatively late in life—his first album (as the French call their bound comic books) wasn’t published until he was forty years old, in the early eighties. From his earliest works, Baudoin focused on autobiography, making him one of the first French cartoonists to explore this genre, which has gone on to become one of the most prominent features of European literary comics. At the same time, his art—already confident, with an inky expressionist manner reminiscent of his contemporaries Jacques Tardi and José Antonio Muñoz—evolved quickly into a daringly loose, calligraphic brush style that has made him one of the most respected and recognizable cartoonists in Europe.

After Baudoin’s first few albums, Étienne Robial—the legendary graphic designer and cofounder, along with Florence Cestac, of Futuropolis, one of France’s most influential independent publishers—prodded Baudoin to break with traditional narrative structure. Shortly thereafter, an epiphanic Miles Davis concert gave the cartoonist the courage to start improvising in his work by introducing digressions, elements of collage, and postmodern authorial interruptions. Books like Un flip Coca! and Un rubis sur les lèvres are full of jarring juxtapositions and shifts in style. A few years later, Couma acò harnesses this jazzy, improvised style to the form of a more classical family memoir, a template Baudoin has returned to numerous times, notably in Piero, published in English this month by New York Review Comics. Couma acò was also his first big critical breakthrough, winning him the prize for best album of the year at the Angoulême International Comics Festival in 1992. He would go on to win two scriptwriting awards: for Le voyage in 1997 and for Les quatres fleuves (in collaboration with the mystery writer Fred Vargas) in 2002.

Baudoin’s focus on everyday life, his unconventional drawing, and his philosophical, self-questioning approach to memoir set him apart from better known contemporaries like Tardi or Jacques Loustal. He had to wait another decade or so before a new generation of artists and publishers, centering around the Parisian publishing collective L’Association, would claim him as one of their own, making of him a crucial bridge between their punk, DIY new comics wave and the more classicist auteurs Baudoin came up with. He remains much admired and respected by both camps to this day.

At age seventy-six, he continues producing books and drawings at a furious rate, giving lie to the maxim that comics is “a young man’s game,” as R. Crumb has said (himself another septuagenarian who still cranks out a two-hundred-page book when he feels like it). Speaking of Crumb, it was he and Aline Kominsky who gave Americans their first taste of Baudoin’s work some twenty years ago in the last issue of their anthology Weirdo—an issue put together from their new home in Southern France, with the English title, Weirdo, replaced by the phonetically Frenchified Verre d’eau.

To some extent, Piero stands apart in Baudoin’s oeuvre. It was commissioned by a short-lived comics imprint of Seuil Jeunesse, the young-adult wing of a major French publisher, in an attempt (alongside many other mainstream publishers at the time) to repeat the success L’Association was having then with its simple yet elegant paperback comic books. In that period, L’Association managed to retain their artistic credibility while also publishing the occasional best seller, like Emmanuel Guibert’s La guerre d’Alan and, most notably, Marjane Satrapi’s blockbuster hit Persepolis. Inspired by this model, Seuil put out a series of trade paperback–size comics, nominally destined for young-adult readers, made by authors poached from this burgeoning French indie scene. Baudoin created Piero and one other book for them, a fable about a young boy living in Nice called Mat, before the imprint shut down. (The books have since been reissued in France by the publisher Gallimard.)

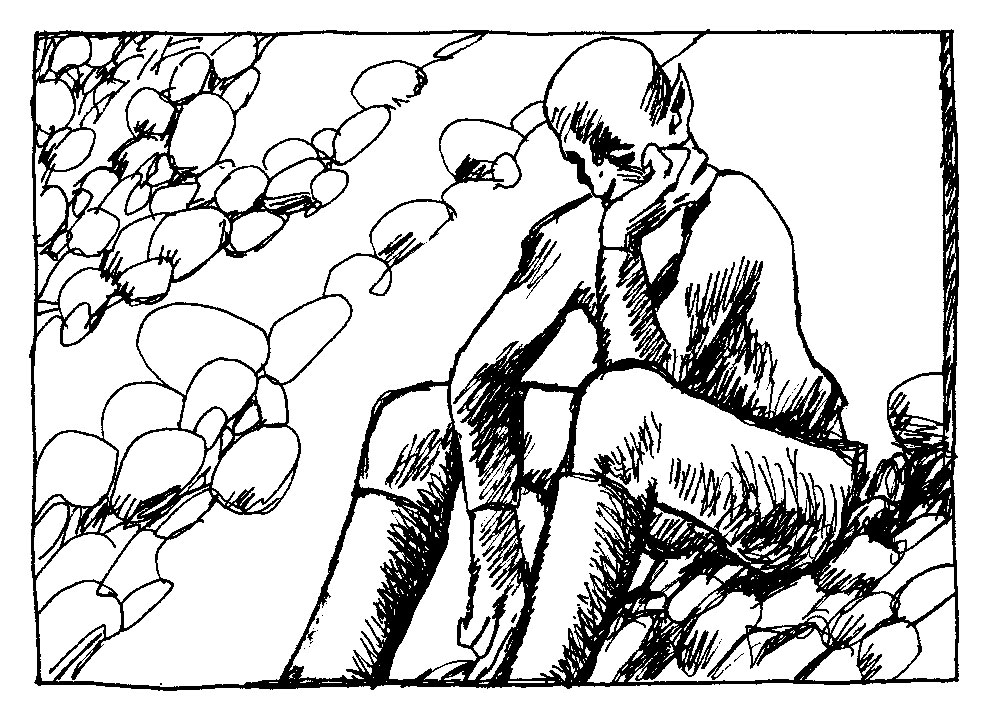

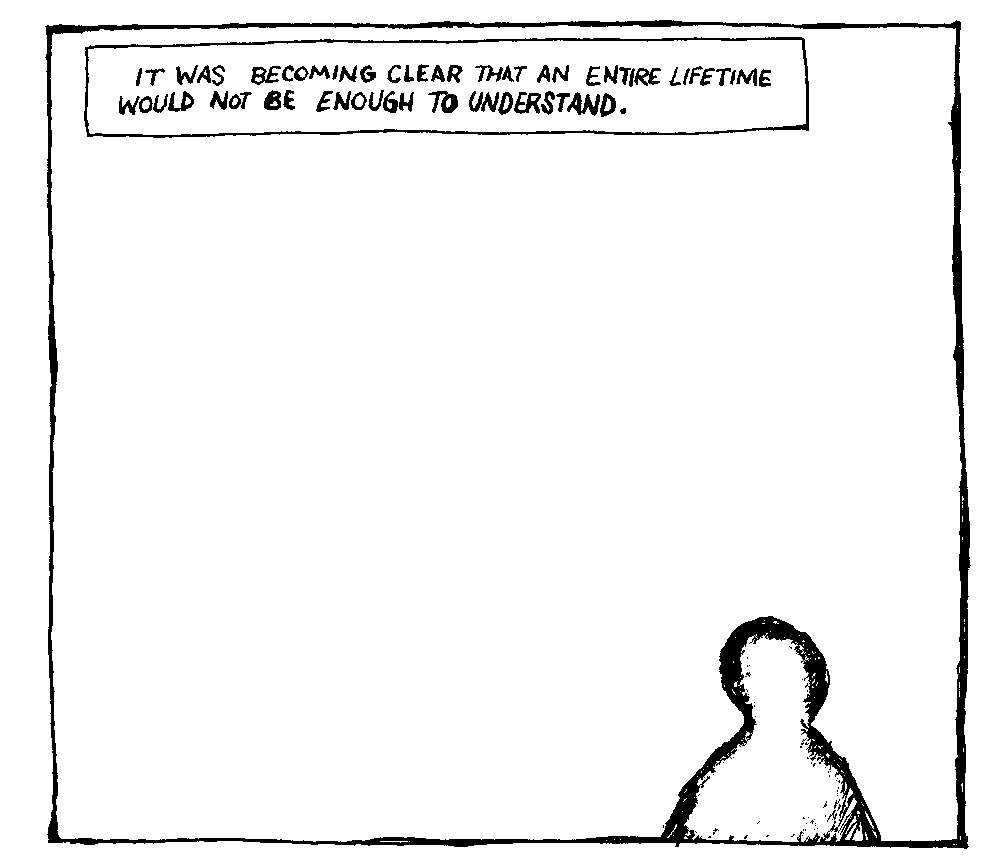

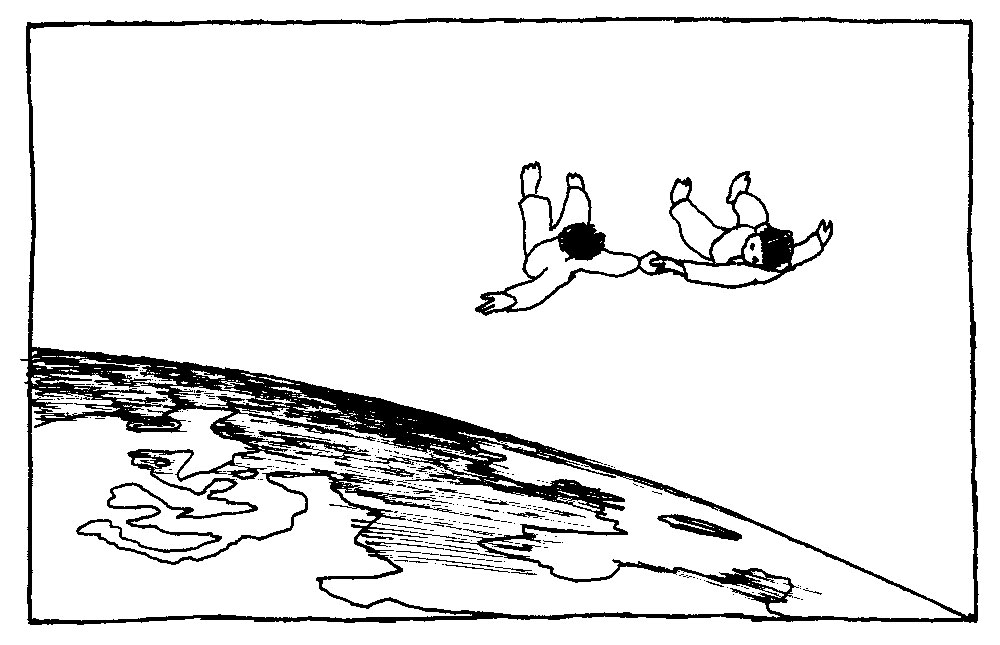

To readers familiar with Baudoin’s work, what’s most unusual about Piero is that it does not feature his trademark virtuosic brush art. Instead, he opts for the busy, scratching, and scribbling lines of a Rotring ArtPen, presumably in order to emulate the ballpoint pens and pencils with which the young protagonists are constantly drawing. Perhaps he also aims to create a sense of intimacy in this smaller-than-usual format (a typical French album is about eight by twelve inches), much the way Art Spiegelman chose to draw the art for his book Maus at the actual size it would be printed, instead of drawing the original art half again or twice as large—a common technique cartoonists use to make their art look better when printed. Personally, I love the pen drawing in Piero, and if it’s not as flashy as Baudoin’s brushwork, it just goes to show that he doesn’t need flashy virtuosity to create an indelible image. Just look at the forlorn Martian above, or admire the graceful simplicity below of the two boys floating in the outer space of their dream world. Furthermore, the choice of pen underscores an important quality of Baudoin as an artist: that above all, he is interested in using drawing to tell stories and to examine life and the nature of art.

The scene we enter in Piero is the modest world of Momo (as Baudoin was called as a child) and his older brother, Pierre, nicknamed Piero, living out their childhood between an apartment in Nice, where their father worked as an accountant, and, more important, a tiny rural hamlet called Villars-sur-Var, where he and his brother would spend their summers (and where Baudoin still spends part of the year, alternating with his cozy studio in Paris). This sun-bleached, woody terrain, full of creeks and valleys, is a recurring setting in Baudoin’s work. He has drawn it countless times and from countless angles, never tiring of exploring its rich forms and emotional resonances.

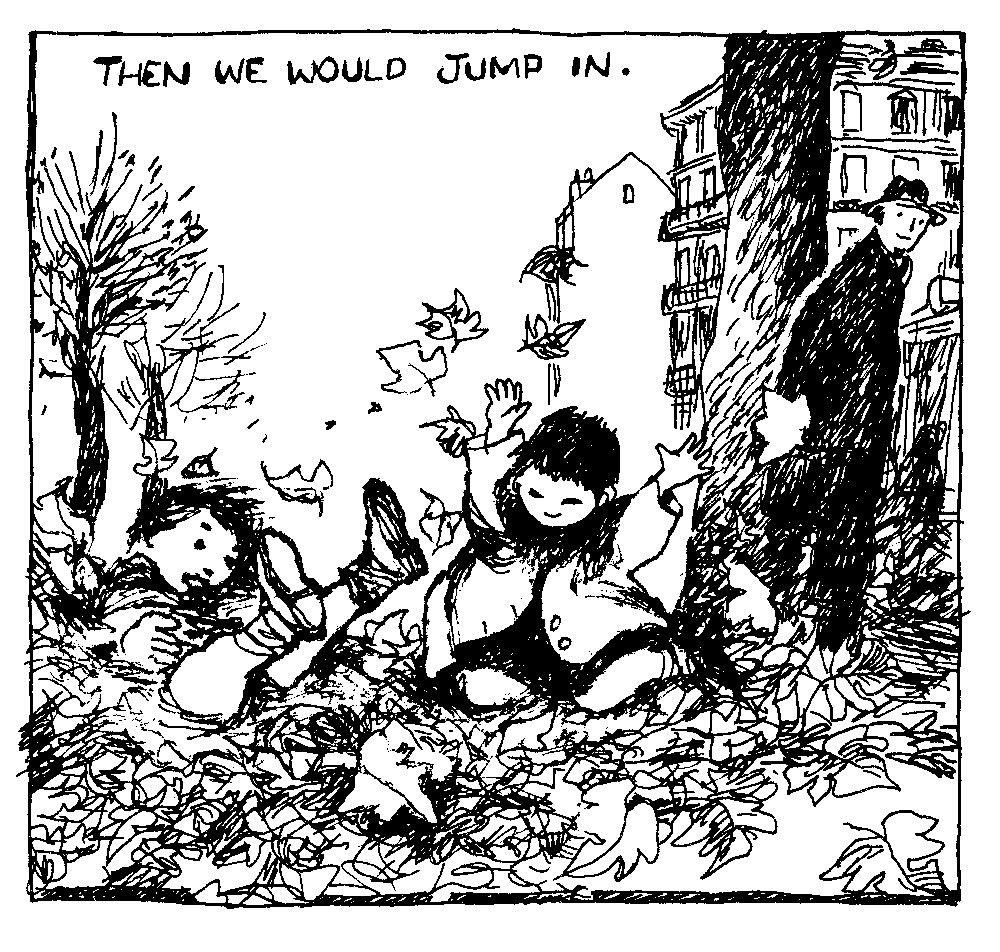

A particular charm of Piero resides in Baudoin’s ability to evoke the creativity of children at play. When I read the scenes showing the two siblings drawing together, it puts me immediately back in my own childhood fantasies, my younger brother and I devising invisible city blocks along the apartment hallway where we and our stuffed animals (we dubbed them the “Sweeties”) could drive around in miniature cars. Similarly, I observe my own eight- and ten-year-old children hunched over a piece of paper, punctuating long stretches of silent concentration with giggles, and I think of Edmond and his brother drawing their epic battle scenes. It’s clear that Baudoin has captured something elemental in these sequences that he presents so matter-of-factly and unsentimentally (which is not to say they are not also suffused with nostalgia).

In a sense, Piero contains the distillation of all the themes of Baudoin’s work, from the places he grew up to the people he knew and, especially, his family. Curiously, although Baudoin’s mother and father show up regularly in his other books, his brother rarely appears except in the occasional passing mention. It’s as if this is the sum of what Baudoin feels he has to say about his brother and the influence he had on him. It is in many ways akin, though with much less tragic contours, to Crumb’s idolization of his older brother Charles, who similarly rejected art, leaving the task—perceived as an almost holy duty—to his younger brother. Piero is in this sense an origin story that ends with Baudoin in the position of James Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus at the end of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, about to go forth and encounter the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of his soul the uncreated conscience of his race.

Matt Madden is a translator and cartoonist. He is the author of 99 Ways to Tell a Story: Exercises in Style, which is a comics adaptation of Raymond Queneau’s Exercises in Style, and of two textbooks cowritten with his wife, Jessica Abel: Drawing Words & Writing Pictures and Mastering Comics. Madden and Abel were series editors of The Best American Comics for six years. He lives in Philadelphia.

From Piero, by Edmond Baudoin, translated from the French by Matt Madden. Excerpt and images courtesy of New York Review Comics.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2zyg70c

Comments

Post a Comment