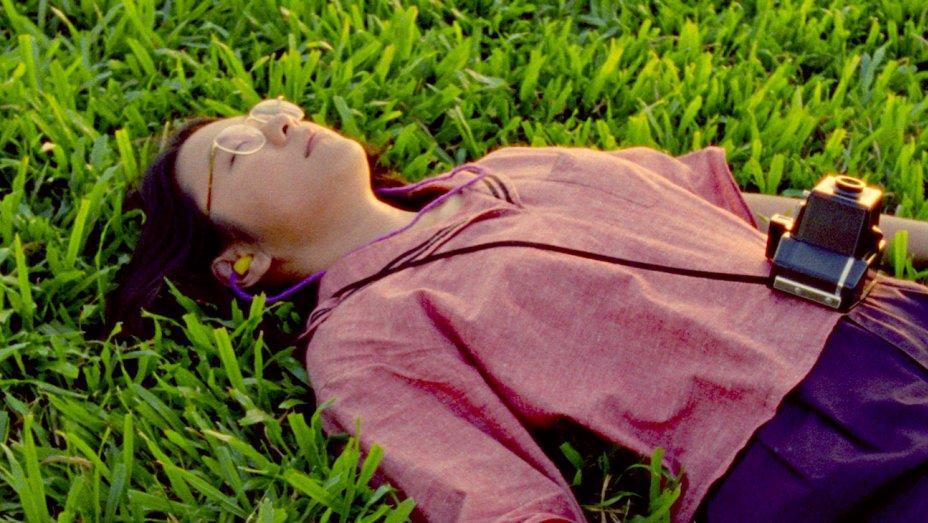

Little did Sandi Tan know, her first (and only) feature film, Shirkers, would escape her in the exact way its namesake prophesied. In 1992, Tan wanted to write a movie that preserved her punk upbringing in Singapore. Nineteen-year-old Tan and her friends fancied themselves iconoclasts, abrading against a stiflingly conservative art scene; they led dozens of minor revolutions, from chewing gum (which was against the law) to watching bootleg copies of Blue Velvet via “clandestine videotaping syndicate.” Inspired by the “unusual” and “unpopular” films of French New Wave and independent American cinema, Tan concocted an idea for her own: a guerrilla-style road movie in a country that takes only forty minutes to drive across. It would be bold and bright and fizzling with youthful energy, exuding all the naive ambition of a sure-to-be cult hit. Only it never was, because Shirkers was never finished. After filming was completed, all seventy reels were stolen by Tan’s mentor and director, Georges Cardona. It took more than twenty years for Tan to be reunited with Shirkers. She sprinkles the surviving footage into a breathtaking Netflix documentary in which she spends remarkably little time pathologizing Cardona, choosing instead to entertain a more nostalgic, meaningful subject: how Shirkers (and its absence) has rippled through the lives of its creators, cast, and crew. Tan in particular feels that she has been permanently fissured by the vacancy that Shirkers left behind, not only in regards to her own childhood but also the place her work should have occupied in Singapore’s film history. Alongside her crew members, Tan wonders: Is it possible for the lack of something to be felt, even though it never really existed in the first place? But in the end, Shirkers isn’t just Tan’s wish for what could have been; it’s a beautiful and backward odyssey, chasing down and interrogating her past to find out precisely how her innocence fell by the wayside. —Madeline Day

Yanick Lahens is not much known in the U.S., but critics are right to call her one of the most important living Haitian fiction writers. There are but three of her books available in English translation, the most recent of which is the stunning novel Moonbath, from Deep Vellum. Moonbath’s narrator, Cétoute Olmène Thérèse, weaves together a compact but nonetheless epic family narrative set in a rural Haitian village. Power and corruption are ever present, and their pressures—be they sexual or economic or both—are often impossible to reckon with or escape. What’s most surprising, though, is the sense that one has fully waded into the world these characters inhabit, a world so alive that I sometimes forgot I was reading a book at all. In many ways, I’m reminded of first reading of Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, a book that similarly transported me clean out of my self and into some other world beyond. —Christian Kiefer

You know that indentured heaviness you feel on a night (always ones before you must be up early) when against all methods, you simply can’t fall asleep, and you watch the clock tick well past two and then four? That endlessness is exactly what I felt the first time I read Shirley Jackson’s short story “The Bus” years ago. Although not as violent as “The Lottery” or as spooky as We Have Always Lived in the Castle, it’s still completely dreadful and mind-consuming. Anyone who’s read Jackson’s work knows it’s a disservice to say too much, so I won’t. “The Bus” will take you about ten minutes to read, and it will haunt your brain for a lifetime. —Eleonore Condo

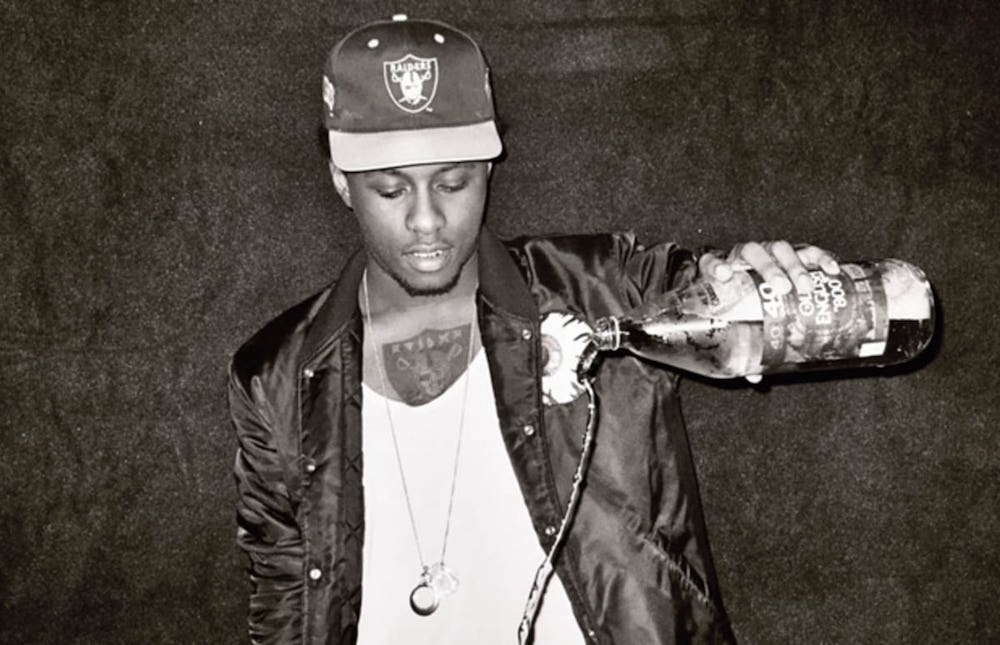

One of the great tragedies of the streaming era is the death of true discovery. As the rap critic Andrew Nosnitsky has noted on Twitter, the corporatization of music and media consumption benefits only the Monopoly men who hold the money. Any whiff of weirdness is rinsed out. All sharp edges of genre defiance and genuine revolution are cleaved off and smoothed. But when I was in college, musicians were just beginning to reckon with the possibilities of the Internet. Out of the ether would come baffling things: bedroom black-metal artists recording howling EPs over Garageband drums, indie bands revivifying the sound of nineties Chicagoland, Minnesota tweens singing dead-eyed R & B. One of my favorites to emerge from this renaissance is SpaceGhostPurrp’s NASA: The Mixtape, a mysterious rap project with a picture of the Hanna-Barbera character Space Ghost emblazoned on the cover. Clocking in at just under a half hour, NASA: The Mixtape serves as a perfect introduction to one of modern rap’s most influential and elusive figures. SpaceGhostPurrp’s reference points are Three 6 Mafia, Eazy-E, and Lil B, all of whom Purrp synthesizes into an extraordinarily otherworldly sound. He isn’t a terribly gifted rapper; instead, the appeal here is his intuition for building a spooky intergalactic atmosphere. His beats are blown out, gritty, and pulsing with dark matter. He repeatedly samples the pips and whirrs of Space Cadet, the pinball game that came packaged with Windows 95. As an artistic statement, NASA: The Mixtape stands out even eight years on from its release, but Purrp’s career stalled soon after. In the years since NASA, SpaceGhostPurrp’s friend ASAP Rocky rose to superstar status, Three 6 Mafia experienced a favorable critical reappraisal, and Florida became a hotbed for rising stars rapping over murky 808s and lo-fi synths. But SpaceGhostPurrp receded into the shadows. He’s seemingly allergic to fame. On “I LOVE LEAN,” he raps, “I’ma change the rap game / Can’t sell my soul for green”—a throwaway line in 2010, but an oddly prophetic one from today’s vantage. —Brian Ransom

The first line of Kate Tempest’s new collection, Running upon the Wires, is at odds with her name: “Even the rain was quiet.” However, Tempest’s work is anything but: she is a spoken-word performer, and her bent for the music of language emanates even from her written word. I was transfixed by her command of rhyme, by the serious, bard-like quality of verse meant to be sung. The collection is the story of a relationship in three parts, moving from “end” to “middle” to “beginning”; in a deft handling of shuffled narrative time (perhaps rightly likened to Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind), Tempest presents intimately human scenes, composing small portraits of joy, pleasure, obsession, betrayal, insecurity, and loneliness that are honest and vulnerable. —Lauren Kane

In Walker Percy’s novel The Moviegoer, the protagonist, Binx Bollings, occasionally seeks out what he calls “repetitions”—sitting in the same seat at the same movie theater watching the same movie, for instance—“toward the end of isolating the time segment which has lapsed in order that it, the lapsed time, can be savored of itself and without the usual adulteration of events that clog time like peanuts in brittle.” I, too, practice repetitions, though not, like Binx, to drop from linear time and chew on its shadow but to put my ear to it and listen to its unspooling. As the center of old steps go smooth and concave from the thousands of feet that have pressed and brushed them, repetitions cumulatively alter the shape of places and things in the mind, in memory. To witness, returning, how a place has changed in your perception, to press your fingers again to the old indentation, is to feel, ever so remotely, the contours of passed time, catch a shimmering glimpse across a canyon of who you once were. Whenever I’m in Chicago, I go to BLUES club on Halsted Street; whenever in New Haven, I eat at Frank Pepe’s pizzeria; whenever in Delhi, I visit the Jama Masjid and eat a Shami kebab at Karim’s; and whenever I’m in Berlin, I march through the Bode Museum, the sculpture gallery on Berlin’s Museum Island, past rooms of German and Italian, Gothic and Renaissance masterworks of statue and altarpiece, to see but one artist—Tilman Riemenschneider, the late-Gothic sculptor of Würzburg. Riemenschneider, a genius in wood, is devoted to the vividness, shading into lushness, of his human figures, his saints and apostles, whose expressions are more puzzled than beatific, as if surprised to be so lushly corporeal. Proportionally, they are slightly off—like infants, the heads are too big for their bodies, the fingers very long and thin—though one gets the sense that this is a result of Riemenschneider’s hypertrophied attention to detail, that he is simultaneously attending to each area in close-up. Every vein on a hand is articulated, each facial wrinkle deep-riven. His figures are always extravagantly haired and robed, overflowing with folds and ringlets, as if his exuberance demanded he expand the canvas however possible. They are good company, always content, always new. —Matt Levin

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2JzmCDX

Comments

Post a Comment