We’re away until January 2, but we’re reposting some of our favorite pieces from 2018. Enjoy your holiday!

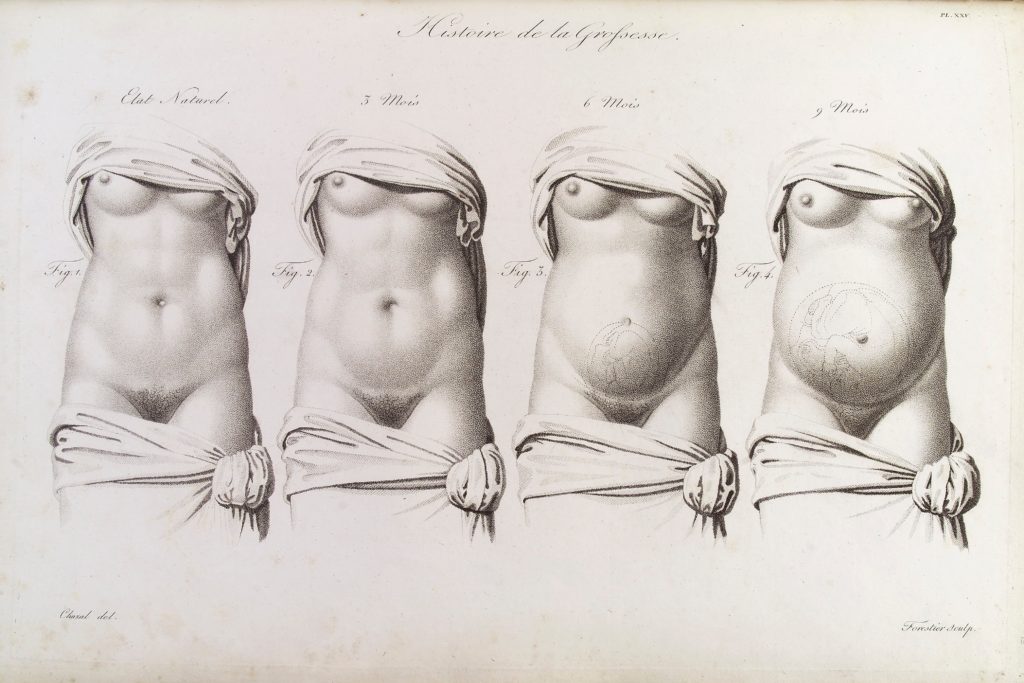

Stages in pregnancy as illustrated in the nineteenth-century medical text Nouvelles démonstrations d’accouchemens.

I wrote the first draft of my novel Heartbreaker in a ten-day mania in August 2015 with a fist-size bandage over my left ear; beneath it, a track of dark-blue stitches. The smallest bone in the human body, my stapes bone, which is charged with conducting sound in the middle ear, had stopped working. I now had a thin hook of titanium fluttering in my head, and in the on-switch manner of miracles, my hearing returned.

My husband had taken our two young sons on a road trip to a small cabin on the east coast of Canada. I could not lift anything heavy. I had to keep my heart rate low. I could not wash my hair and wore it in a knot shined with grease on top of my head. I turned off my cell phone, unplugged our landline, and disconnected from the Internet. This was my plan: to be unreachable. Didn’t Jonathan Franzen pour cement into his USB port and work in some kind of carpeted hell-mouth of a rental office to finish—which one was it now? Ah yes, Freedom?

My husband could see I had a novel inside me, and it was a commotion, and the only way to settle it was to write it, and the only way to write it was to be alone. I had not been alone in a decade. I had not been alone because I am a mother, and a mother is never alone. When she is washing, sleeping, raging, she is not alone. For a mother, this is the state of things. Children hang from your clothing. They pummel you with questions. Like a gunfight, like the most consuming love, like an apocalypse: they take up all of the available space.

from The Paris Review http://bit.ly/2LDV2Gz

Comments

Post a Comment