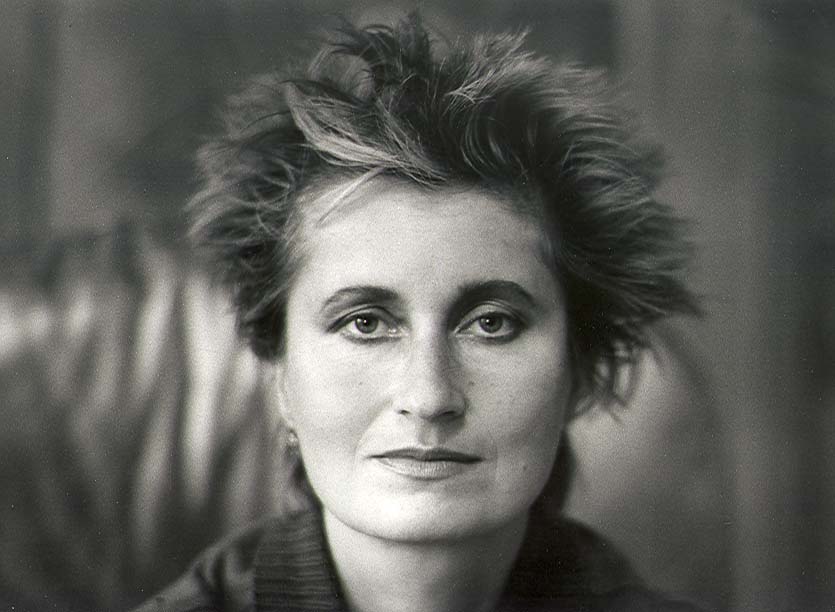

Emily Allan and Leah Hennessey’s play SLASH is so enjoyable it’s like having dessert for two hours with no intermission. One of advertisement describes it as an “attempt to transcend the banality of identity and the terror of consciousness,” but I prefer the Instagram promo with an image of Camille Paglia in men’s clothing wielding a switchblade in front of a urinal. That’s much closer to the play’s prankish genius. Every dynamic (or adversarial) duo from popular culture whom you’ve probably been obsessed with at some point appears for a romping ten minutes or so, from Spock and Captain Kirk to Lennon-McCartney to Morrissey and Johnny Marr. The hints of homosexuality in these pairings are the source of a great deal of the comedy: it’s the most fun meditation on the eroticism of collaboration since Wayne Koestenbaum’s Double Talk. The best bit is probably the one that’s getting the most hype, a reenactment of some shade from the early nineties thrown around by Paglia and Susan Sontag, but take my advice—wait for the real thing and don’t watch the clip of it online from last year. In person, Allan (Paglia) and Hennessey (Sontag) sound so much like their respective muses that if you close your eyes, you’ll have an opinion on The Volcano Lover again. SLASH runs through Sunday, December 23, at MX Gallery in Chinatown. —Ben Shields

Spotify just informed me that my most listened to song of 2018—above even “Femmebot,” by Charli XCX—is a floaty, almost half-hour-long drone called “Being Here,” by a seventy-five-year-old New Age artist named Laraaji. If you’re writing or studying in a city like New York, playing this song in your earbuds is like activating a force field. A lot of ambient music makes me feel like I’ve woken up in a simulated reality. For me, a defamiliarizing anxiety feels redundant in 2018. But Laraaji’s drones are reassuring—and somehow optimistic. He was a comedian before he became a musician, and he seems like the kind of guy who sleeps flat on his back with an enormous smile on his face. A street musician in the seventies, he happened to be playing in Washington Square Park when Brian Eno, the Socrates of New Age, heard his zither and offered him a record contract. Since I discovered Laraaji’s music, I feel like I see his Jeff Goldblum–like twinkle everywhere I google. He teaches “laughter meditation” and recently dropped a new EP, Arrive without Leaving. We may live in a distorted, unfunny rendition of Jerzy Kosinski’s Being There—but at least we also have Laraaji’s “Being Here.” —Brent Katz

As my colleagues are well aware, I’m somewhat obsessed with the work of the Austrian writer Elfriede Jelinek, winner of the 2004 Nobel Prize in Literature. While here in the U.S. she’s probably best known for her 1983 novel, The Piano Teacher, she’s also a prolific playwright and essayist in her native German, exploring such themes as Europe’s asylum policies (The Supplicants), the Charlie Hebdo shooting in Paris (Anger), and even the election of Donald Trump (2017’s On the Royal Road: The Burgher King). I’d never read any of her plays until last week, when I picked up Sports Play, her 1998 look at the primacy of contemporary sports culture. But even as someone lacking much of a background in theater, I’m now a convert. What’s it about? That’s not entirely easy to say—it’s essentially plotless, composed instead of a dense series of monologues concerning the culture of sports and the obsession with gym-honed human bodies. Sports as war is a reoccurring motif, as is the history of sports and even a few obliquely autobiographical references to the death of Jelinek’s father. Like all of Jelinek’s work, it’s intense, strange, cruel, and at times mischievous. It’s also completely brilliant, even just read on the page, and I’m now intensely curious to see what it’s like performed onstage. —Rhian Sasseen

Come here, beckons the translator Yasmine Seale, as if holding in a secret: “I want to show you some wonderful things.” In her new translation of Aladdin, Seale provides a scintillating lens through which to view “the tale that has never stopped traveling”: the story of a boy and his magical lamp. Paired with a riveting introduction by Paulo Lemos Horta, Seale’s work acknowledges the tangled history of Aladdin, from its initial appearance in French literature in 1709 to its controversial Disney-fication in 1992. Seale and Horta uncover that Aladdin is one of the handful of “orphan tales” that snuck into Antoine Galland’s French translation of The Thousand and One Nights after Galland heard it recounted by a nomadic Syrian storyteller. Since then, Aladdin has accumulated countless many more layers of voices spanning from Charles Dickens to Salman Rushdie. However, instead of severing or distinguishing herself from Aladdin’s complicated origin, Seale approaches her own translation mindful of the story’s Syrian-French hybridity as well as its context in the greater framework of the narratives of Scheherazade. What results is an elaborate poetic tapestry so glamorous and delightful that you can’t help but want to read again. —Madeline Day

I walked into a ten-thirty showing of Mandy worrying that I might fall asleep. When I left two hours later, I wondered how I could go to bed: even my weirdest dreams can’t compare to the churning beauty of Panos Cosmatos’s new film, in which every shot is a murky molasses nightmare. Mandy has been pitched as a revenge flick á la John Wick, which it is, as well as as a religious-cult film, which it also is, but neither of these labels is entirely accurate. This is a midnight movie in the classic sense, a howling shaggy dog that’s as much Jodorowsky as it is Sunn O))), and like many midnight movies, Mandy shrugs away labels and demands you meet it on its own terms. The plot is slow, almost as sludgy as the soundtrack’s metal guitars. The camerawork, incredible as it is, crawls, ensuring that every scene lasts a full minute longer than you’re expecting it to. But once you learn the rules of Mandy, it’s impossible not to be charmed. There are chainsaw fights, crossbows with scopes, stupidly huge blades. A good deal of this charm can be attributed to Cage, who gives an incredible performance. He stumbles into a well-lit bathroom, roars as he guzzles vodka straight from the bottle and pours it into his wounds. He headbutts demon bikers, smears blood on his face, lights cigarettes on flaming skulls. When the final scene rolled around—in which Cage is grinning, drenched in red light—I, too, was grinning just as wildly, and I realized that I was looking in a mirror: seeing this strange beast of a man, unhinged, and recognizing myself in him. Great art lifts you out of yourself, and Cage’s special talent is to lift you out of your own body, yes, but also to place you in his own, to force you to tap into the horrible static of being alive. —Brian Ransom

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2GkDRuH

Comments

Post a Comment