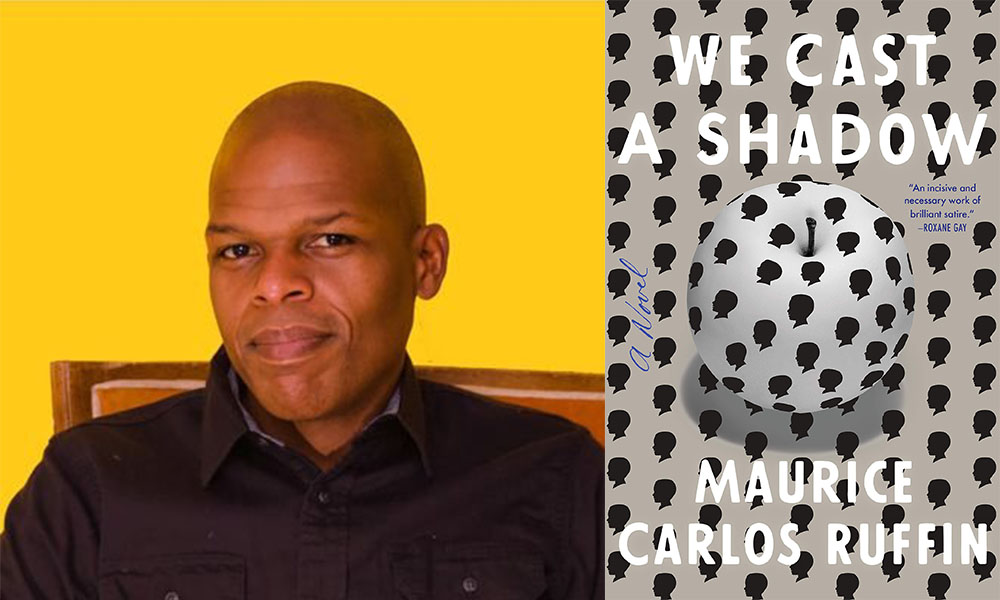

Maurice Carlos Ruffin’s debut novel, We Cast a Shadow, is narrated by an unnamed black father who is desperate to protect his mixed-race son from white supremacy. His solution is to erase his son’s blackness. He applies whitening cream on the boy’s skin to burn out birthmarks, causing young Nigel to double over in pain. In the father’s mind, the son’s birthmarks are spreading, and his attempts to erase his son’s identity become increasingly frantic.

I grab his shoulder and spin him around. The dark medallion of skin on his tummy is bigger. Nigel’s other blemishes cover his body. The greatest concentration of marks: belly and back. A dark asterism. Some flaws approach the size and complexity of the stigma on his face … My fear is that these islands will merge to form a continent.

The boy’s white mother is vehemently against the treatments, and so they remain a secret between father and son. Almost everything the narrator does—his aspirations in the powerful, mostly white law firm where he works, his deception of his wife—is done in the hope of providing a better life for his son. At the firm, in order to get a promotion, he engages in disingenuous outreach to people of color, selling out his community while civil unrest in the city intensifies. At times the reader might despise the narrator, but Ruffin deftly reminds us that the real culprit is white supremacy.

The world is a centrifuge that patiently waits to separate my Nigel from his basic human dignity. I don’t have to tell you that this is an unjust planet … A dark-skinned child can expect a life of diminished light. This is the truth anywhere in the world and throughout most of history.

Ruffin and I are friends whose paths sometimes cross in New Orleans. About once a year, we attend an odd expo event together on the city’s outskirts. Last summer we attended the National Preppers and Survivalist Expo, which was a convention room filled with mostly white men preparing for what they thought might be the next civil war.

More recently, we went to the New Orleans Oddities and Curiosities Expo, where the tiny bones of animals were arranged into art. A couple weeks later, we met for lunch at a popular Mid-City restaurant called Juan’s Flying Burrito and discussed the inspiration for his complex narrator.

INTERVIEWER

What initially feels like a father’s protective love escalates into something much more sinister. The narrator is given several opportunities to reflect on his behavior, but can’t seem to see himself clearly.

RUFFIN

Definitely. The narrator’s primary identity is a father. I’m not a parent myself, but I think to be a parent is to be a zealot—somebody who has entered the religion of fatherhood and motherhood. Being religious means that you’re going to follow those tenets to their logical conclusion, and almost every major religion has an element of sacrifice. The narrator’s mother is against his behavior, his wife is against it—so every time he has to overcome an obstacle, he has to overcome it on behalf of Nigel and on behalf of being a good father. He learns how to be more and more extreme. I toyed with the idea of naming the book “Nigel,” because in the same way that in Lolita Humbert Humbert’s quest is really all about Lolita, in this book the narrator’s quest is really about Nigel.

INTERVIEWER

The narrator seems more concerned with being a father than with any other aspect of his own identity. Penny, his wife, is concerned with identity. Nigel is concerned with identity. The father seems to be rejecting identity in the hope of erasing it.

RUFFIN

That really is one of the big issues with white supremacy and racism. The narrator understands that everything that stands in the way of his son having a good life is connected to race, racism, white supremacy, but he’s not an ideologue. He really wants to be this person who is “nonracial,” but he knows it’s impossible. He wants it to be a nonissue and he wants that to be the reality for his son.

INTERVIEWER

For me, as a white guy, I initially found myself disgusted with the narrator’s behavior. At first, that disgust was focused solely on the narrator, and then I realized that I wasn’t taking responsibility for my own role in the white supremacy that sets the conditions for his madness. This is part of the reason why I think this book is so important. It showed me my own weakness, and my own false judgment.

RUFFIN

The narrator is definitely a product of his environment. A lot of what’s going on in the book is just like present-day America—the protests, the violence, slavery, facial reconstruction. You can find all of that in the world today.

INTERVIEWER

Your book is often described as satire. But the narrator’s more extreme actions—like using whitening cream and facial reconstruction—have been common enough practice for years. What exactly about the book is satire?

RUFFIN

I think it’s about the level of awareness of the person interacting with the book. This narrator taught me a lot about America and white supremacy. Sometimes we’re sleepwalking through life. A lot of my white friends tell me they keep becoming more and more aware of what’s going on as they see more and more things in the news. You can go your entire life and not see a photo of a black person being lynched. But black people have always been very aware. Somebody I love and respect said they weren’t sure the whole skin-cream thing was realistic, but I was in New York in a Duane Reade and the product was right there on the shelf.

INTERVIEWER

We haven’t come as far as we think we have.

RUFFIN

Not at all. It’s one of the reasons why I set the book in the future. Really what I’ve seen is it’s a sort of undulation, a sort of up and down. We had slavery, now we have mass incarceration.

INTERVIEWER

And if you’re paying attention you can see that we’re not that far from slipping back into the 1930s or worse.

RUFFIN

We’re never far away from it. The thing is, I believe that America is the greatest country on earth, yet we always have multiple layers of injustice that are operating at any given time. When I was writing this book in 2012, President Obama was constantly shipping immigrants out of the country. Now it’s to the point of taking kids from their parents—and for half of America that’s still no big deal.

INTERVIEWER

Do you remember when we went to the survivalist expo? I remember I invited you because I thought your book was a story about surviving. But then we got there and I thought, What are we doing here? Maurice is going to think I’m an asshole. The expo felt like it was code for something else, like a lot of the people there were probably in a white nationalist militia. If anything, it made it clear to me how many people like that are out there. I was sort of frozen and couldn’t talk to anybody. But you didn’t seem uncomfortable.

RUFFIN

That’s because you got to go as yourself. You’d be hard-pressed to find a black person who doesn’t have to deal with racists every single day. Look, I’m a black man living in the South, which means every day I’ll probably see a truck with a Confederate flag bumper sticker. Militias have always been an arm of white supremacy. But yeah, seeing that survivalist expo was like being on the inside of something I would never have seen otherwise. They weren’t standing around saying, Why are you here, black guy? Which honestly always surprises me. I saw Spike Lee’s new film and there’s a black guy whose job is to be David Duke’s bodyguard, and I’m thinking, Oh my god, he can’t be in the same space as David Duke and the entire Klan of Colorado, but those white supremacists are like, Well, it’s his job to guard, as long as he doesn’t get too uppity, we’ll accept him. And that’s kind of how it works. If I had gone into the expo with an Obama shirt, they would have responded to me differently. And part of that is switching my identity—every black person does that, in some form, every day.

It’s almost as if every black person walks around America with a fence around their body. It separates us from polite society. That’s why radical black activists tend to be poor. They end up in an economic cul-de-sac. You can’t trade, you can’t find a decent job, you can’t improve your skills, you can’t bring in funds.

INTERVIEWER

Whereas if you’re a white activist, you can work at Patagonia or something.

RUFFIN

Yes, indeed. If you’re black, you have to assimilate. Code-switch or identity shift. That’s what the narrator of the book excels at.

Peyton Burgess is the author of The Fry Pans Aren’t Sufficing.

from The Paris Review http://bit.ly/2CV1rJr

Comments

Post a Comment