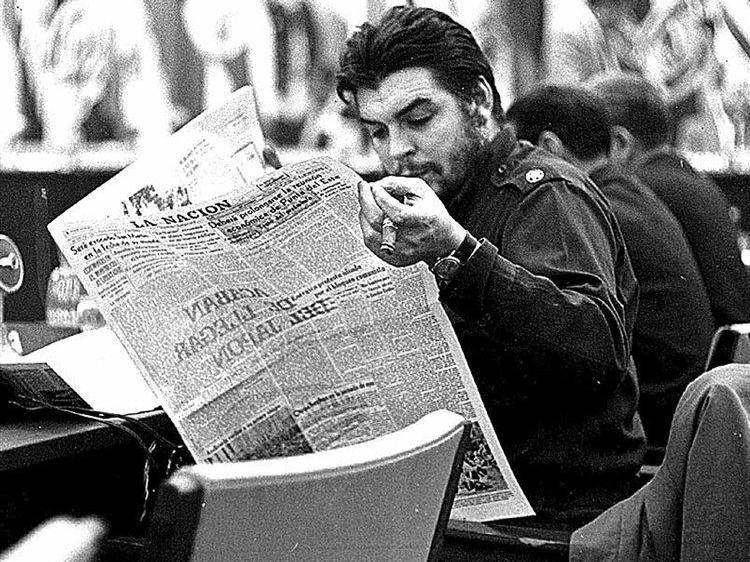

Che Guevara reading the newspaper La nación. Photo: Diario La Nación. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Even Che Guevara, the poster boy for the Cuban Revolution, was forced to admit that endlessly trudging the Sierra had its downsides. “There are periods of boredom in the life of the guerrilla fighter,” he warns future revolutionaries in his classic handbook, Guerrilla Warfare. The best way to combat the dangers of ennui, he helpfully suggests, is reading. Many of the rebels were college educated—Che was a doctor, Fidel a lawyer, others fine art majors—and visitors to the rebels’ jungle camps were often struck by their literary leanings. Even the most macho fighters, it seems, would be seen hunched over books.

Che recommends that guerrillas carry edifying works of nonfiction despite their annoying weight—“good biographies of past heroes, histories, or economic geographies” will distract them from vices such as gambling and drinking. An early favorite in camp, improbably, was a Spanish-language Reader’s Digest book on great men in U.S. history, which the visiting CBS TV journalist Robert Taber noticed in 1957 was passed around from man to man, possibly for his benefit. But literary fiction had its place, especially if it fit vaguely into the revolutionary framework. One big hit was Curzio Malaparte’s The Skin, a novel recounting the brutality of the occupation of Naples after World War II. (Ever convinced of victory, Fidel thought reading the book would help ensure that the men would behave well when they captured Havana.) More improbably, a dog-eared copy of Émile Zola’s psychological thriller The Beast Within was also pored over with an intensity that could only impress modern bibliophiles. Raúl Castro, Fidel’s younger brother and usually an inspired platoon leader, recalled in his diary that he was lost in “the first dialogue of Séverine with the Secretary General of Justice” while waiting in ambush one morning when he was startled by the first shots of battle at 8:05 A.M. Che himself was nearly killed in an air raid because he was engrossed in Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Hours at night could also be whiled away listening to stories. Two rustic poets even took to holding the guerrilla version of poetry slams. A peasant named José de la Cruz, “Crucito,” declared himself “the mountain nightingale” and composed epic ballads in ten-verse guajira (mountain peasant) stanzas about the adventures of the guerrilla troupe. Like a Homer of the jungle, he sat with his pipe by the campfire and spouted comic lyrics, while denouncing his rival, Calixto Morales, as “the buzzard of the plains.” Tragically, the oral tradition was lost to posterity when the troubadour Crucito was killed later in the war. There had not been enough spare paper to record his verse.

But the most beguiling snippet of literary trivia from the Cuban Revolution is Fidel’s assertion during an interview with the Spanish journalist Ignacio Ramonet that he studied Ernest Hemingway’s 1940 classic For Whom the Bell Tolls for tips on guerrilla warfare. Papa’s novel, Fidel said, allowed he and his men “to actually see that experience … as an irregular struggle, from the political and military point of view.” He added: “That book became a familiar part of my life. And we always went back to it, consulted it, to find inspiration.”

“Ernesto,” as the famous American expatriate was fondly known in Cuba at the time, had written the novel based on his experience as a newspaper correspondent in the Spanish Civil War in 1937, and its pages are filled with vivid descriptions of irregular combat behind enemy lines. He had hammered out the manuscript on a Remington typewriter in room 511 of the colonial Ambos Mundos Hotel in Old Havana, never imagining that a similar war would begin in his adopted home. Although it was released when Fidel and his compañeros were still children, they grew up very aware of the best seller (in translation as Por quién doblan las campanas), not to mention the Hollywood version starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman. Fidel first read it as a student; he says he reread it at least twice in the Sierra Maestra.

When it comes to specific guerrilla tactics—the art of ambush, for example, or how to manage supply lines—For Whom the Bell Tolls doesn’t offer much specific insight. There are a few straightforward ideas about, say, attaching strings to grenade pins so they can be detonated from a distance, or descriptions of the ideal partisan hideout. But more importantly, the novel is a perceptive handbook on the psychological element of irregular warfare. The hero, Robert Jordan, is forced to navigate an intricate and alien world, filled with exotic personalities and possible betrayals, much as Fidel’s men did in the Sierra Maestra. Translated to their tropical setting, there are many parallels between the novel and the rebel army’s situation, from the importance of keeping a positive attitude among the troops to Robert Jordan’s rules for getting along in Latin culture: “give the men tobacco and leave the women alone,” mirroring Fidel’s unbreakable rule that village girls never be molested, and the main guerrilla organizer Celia Sánchez’s dogged efforts to keep the men supplied with decent cigars. (Of course, it’s a rule that Robert Jordan breaks in the novel. His torrid affair with the alluring Maria includes a detailed forest romp that can only have impressed the affection-starved guerrillas.)

Although Hemingway surely would have been flattered that the Cuban rebels were reading his work, he was surprisingly silent about the revolution in his adapted homeland. His fishing-boat captain, Gregorio Fuentes, boasted afterward that he and Ernesto had smuggled guns for Fidel in the Pilar, but this appears to have been a tall tale concocted for tourists. In private, Hemingway was disparaging about Cuba’s authoritarian ruler, Fulgencio Batista, and in one letter called him a “son-of-a-bitch.” But Hemingway’s only public protest came when he donated his Nobel Prize medal to the Cuban people: rather than let a government body display it, he left it in the Virgen del Cobre cathedral for safekeeping. (It is still there, in a glass wall case).

Even Batista’s own intelligence service found it hard to believe that Ernesto was neutral, and several times, soldiers searched his Havana mansion, known as La Finca de Vigía, for weapons while he was away traveling. On one occasion, the intruders were attacked by Hemingway’s favorite dog, an Alaskan springer spaniel named Black; they bludgeoned him to death with rifle butts in front of horrified servants. Black was buried in the garden “pet cemetery” by the swimming pool, where he had lolled at his master’s feet for many years. When he returned to Havana, Hemingway stormed in outrage to the local police office to file a report, ignoring the warnings of Cuban friends. A local might have been given a beating, but Hemingway’s celebrity protected him—though, needless to say, no investigation ever resulted. (Black’s grave, incidentally, is still there at the Finca, though no explanation is offered to the steady stream of fans who visit the house.)

During the “honeymoon period” of 1959, when the entire world was enchanted by Fidel’s romantic victory, “Hem” was visited by a string of literary luminaries who wanted to see the revolution firsthand—including, on one occasion, the young founding editor of The Paris Review, George Plimpton. Hemingway and Plimpton were knocking back daiquiris one afternoon at Hemingway’s favorite Havana bar, El Floridita, with the playwright Tennessee Williams and the English critic Kenneth Tynan, when they ran into the officer who was overseeing the executions of Batista’s most sinister henchmen. Plimpton and Williams both guiltily accepted an invitation to attend a firing squad that same night—a morbid, voyeuristic urge that Hemingway heartily encouraged, since, as Plimpton later recalled, “it was important that a writer get around to just about anything, especially the excesses of human behavior, as long as he could keep his emotional reactions in check.”

As it happens, the execution was delayed and the pair never made their macabre rendezvous—a loss for literature that is surely incalculable.

Tony Perrottet is the author of six books: a collection of travel stories, Off the Deep End: Travels in Forgotten Frontiers (1997); Pagan Holiday: On the Trail of Ancient Roman Tourists (2002); The Naked Olympics: The True Story of the Greek Games (2004); Napoleon’s Privates: 2,500 Years of History Unzipped (2008); The Sinner’s Grand Tour: A Journey through the Historical Underbelly of Europe (2012); and most recently, ¡Cuba Libre!: Che, Fidel, and the Improbable Revolution that Changed World History (2019). His travel stories have been translated into a dozen languages and widely anthologized, having been selected seven times for the Best American Travel Writing series. He is also a regular television guest on the History Channel, where he has spoken about everything from the Crusades to the birth of disco.

From ¡Cuba Libre!: Che, Fidel, and the Improbable Revolution That Changed World History, by Tony Perrottet, published by Blue Rider Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2019 by Tony Perrottet.

from The Paris Review http://bit.ly/2MGUFeP

Comments

Post a Comment