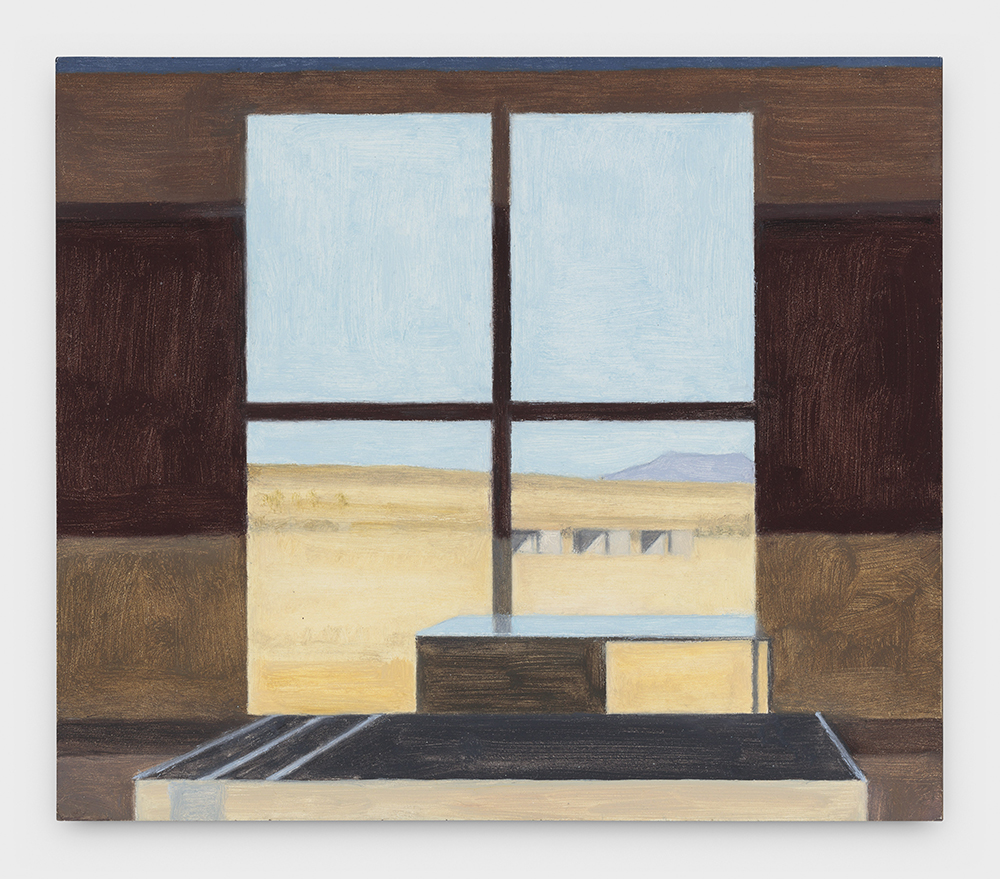

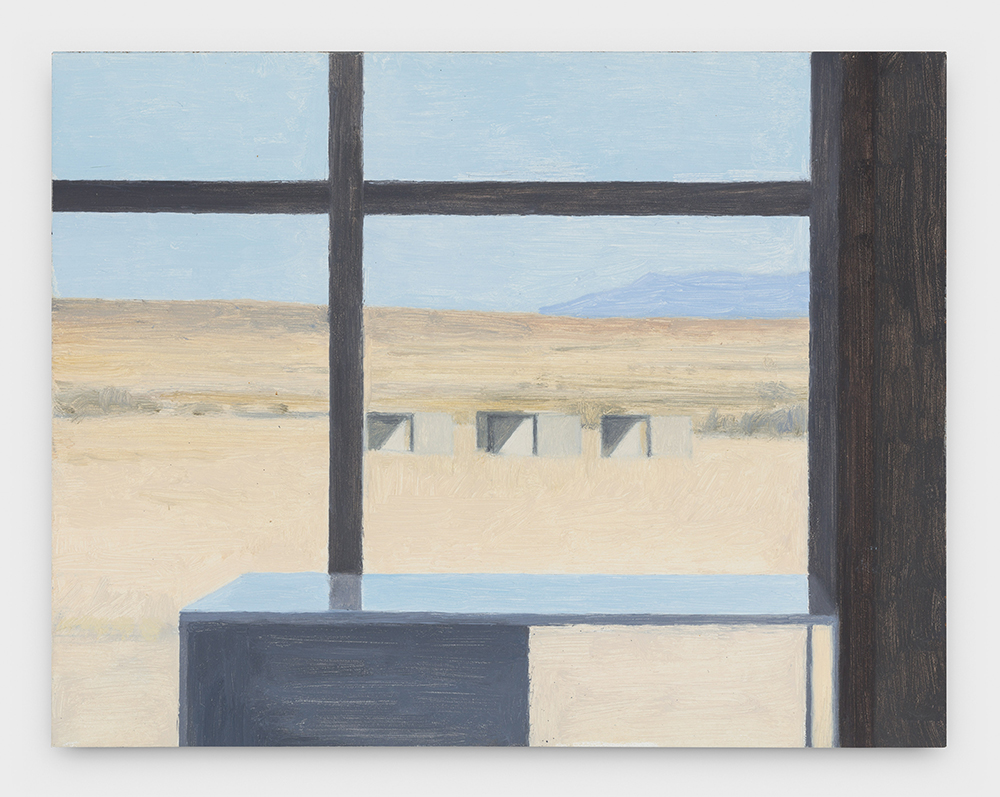

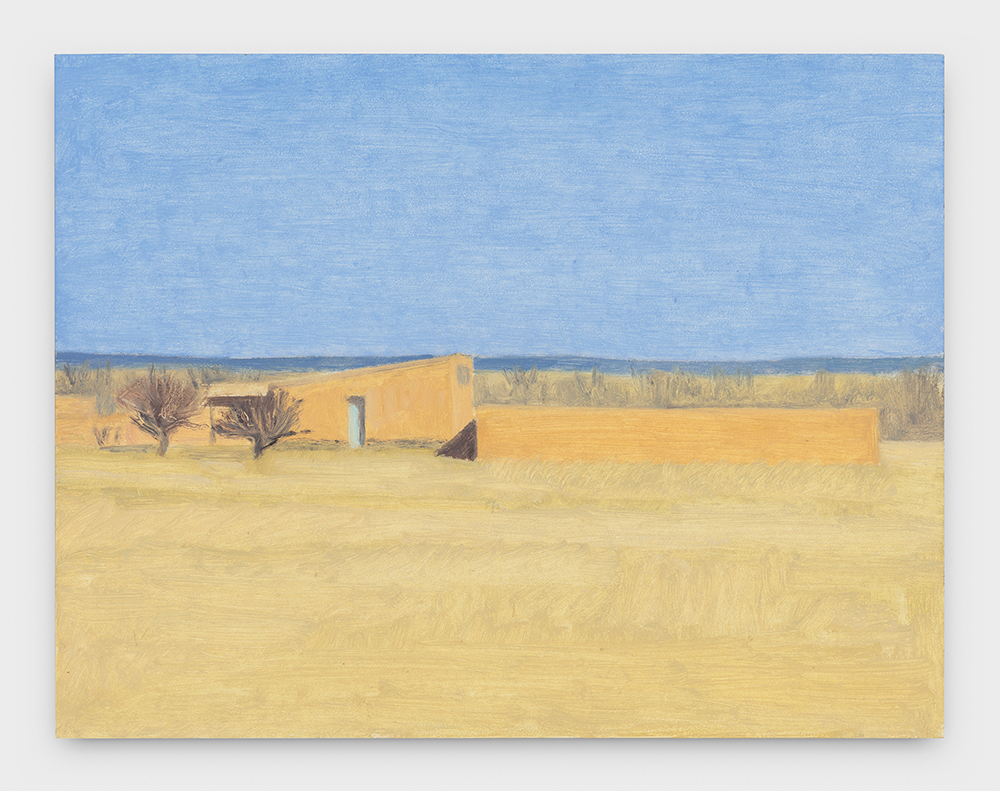

In Marfa, Texas, three hours into the desert from El Paso, the artist Donald Judd installed a hundred geometric sculptures in two disused artillery sheds. Arrayed in a grid are boxes made of milled aluminum, all the same size but each uniquely composed with different patterns of segmented space. Through the sheds’ massive windows, sun and blue sky and yellowed scrub reflect on the aluminum at shifting angles. As you walk through the space, it becomes hard to tell whether you’re looking at a solid sheet of metal or only the illusion of one, created by light.

Photography is banned in the Marfa installation; only a few sanctioned images exist. Photos could never capture the experience of being surrounded by the boxes because pictures flatten the experience, turning it into a shallow singular impression—the Instagram version—rather than the active process of perception that Judd sought. Instead of photos, the young Brooklyn-based artist Eleanor Ray has depicted the boxes in a series of hardcover-book-size paintings that preserve the ambiguity. In Ray’s luminous oils, the walls, windows, and metal alike dissolve into thin brushstrokes that hover between landscape and abstraction. It’s up to the viewer to decide what’s what.

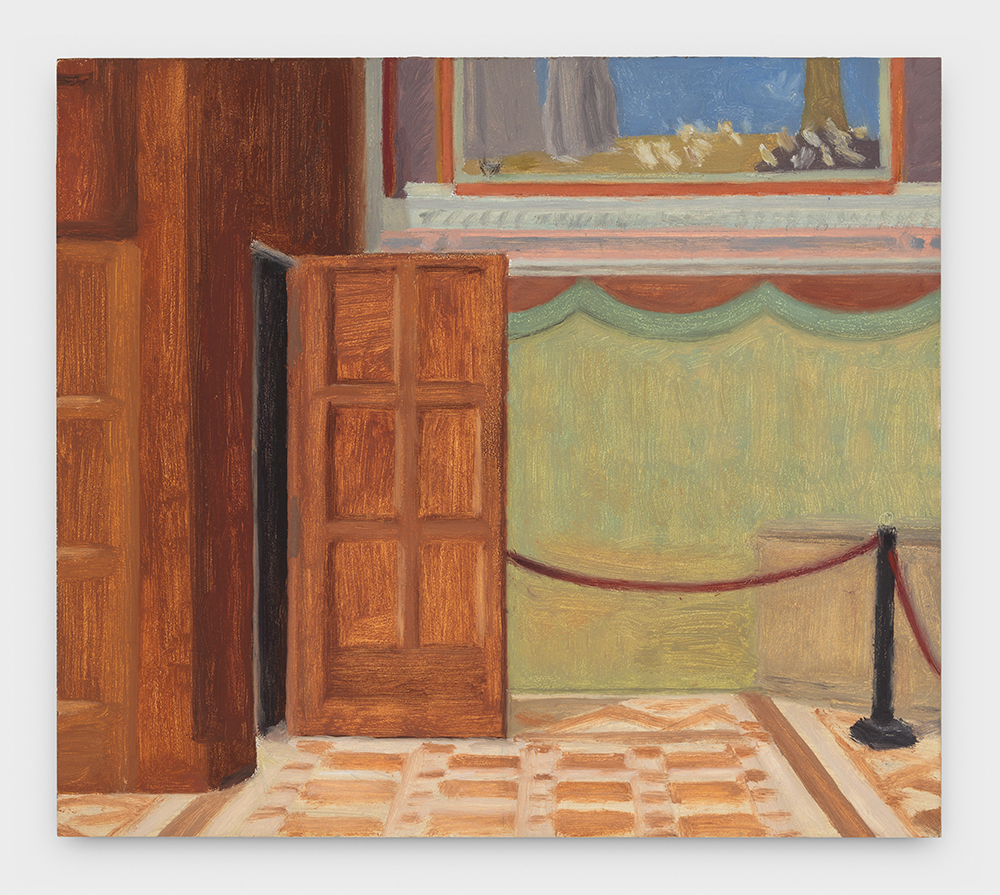

The Marfa paintings are part of Ray’s exhibition at Nicelle Beauchene Gallery in SoHo, on view through February 10. Since 2012, Ray has been drawn to this kind of ekphrastic painting, representing works of art while also capturing the peculiar sensation of looking at an art object, part sensory and part intellectual. Over time, she’s gathered a specific canon of artists who have engaged with the act of seeing in space, some of them mid-century Minimalists and others much older. Ray has painted Judd’s loft in SoHo, Agnes Martin’s house in New Mexico, Piet Mondrian’s geometric canvases hanging in a geometric gallery, and the early Renaissance painter Fra Angelico’s crisp frescoes in San Marco.

Minimalism (a label that Judd and most of the other artists constantly complained about) never adhered to a monolithic austere style; rather, it was about creating work that did not depend on external reference points to communicate its message. As Frank Stella once put it, “What you see is what you see.” Ray’s paintings have a similar effect. They push the viewer into a new way of seeing without the need for massive scale or industrial materials. “I like the idea that the small painting is kind of monumental rather than miniature—that it can contain a bigger space, like the imaginative space of a book,” she said in a 2015 interview with Figure/Ground.

Ray’s interest in creating linear order may be classical and cold, but her colors are lush, as if it were always the golden hour. They bring to mind domestic painters like Pierre Bonnard or Giorgio Morandi, two obsessives who both lent an epic cast to the quotidian. The sensation of looking at Ray’s work is pleasurably transient, like recalling a nostalgic memory or the traces of an artwork you saw long ago.

Assisi (Saint Francis and the Birds), 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York.

Kyle Chayka is a writer living in Brooklyn. His first book, on Minimalism, will be published by Bloomsbury this year.

from The Paris Review http://bit.ly/2MSpygr

Comments

Post a Comment