In her monthly column, Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print books that shouldn’t be.

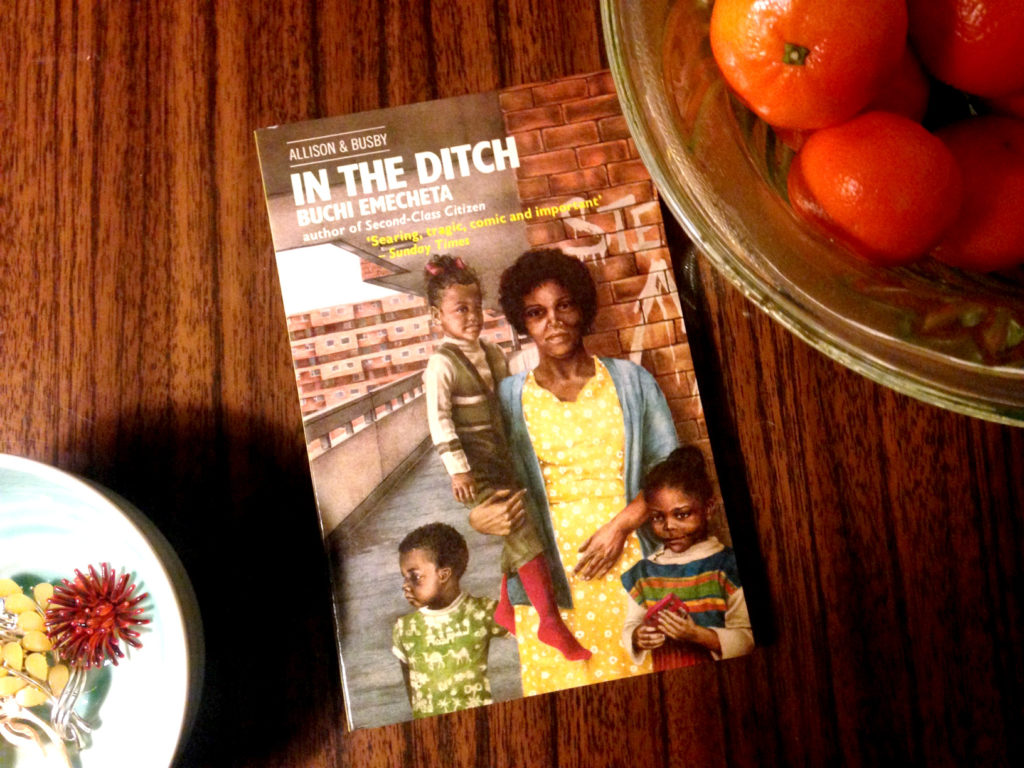

“Who will be interested in reading the life of an unfortunate black woman who seemed to be making a mess of her life?” This was the question Buchi Emecheta asked herself in the early seventies before she began writing what would become her first published novel: In the Ditch (1972). Closely based on Emecheta’s own life, it’s the story of Adah (the author’s fictional alter ego), a young Nigerian single mother living on a London council estate. Like the other “problem” families around her, Adah’s doing her very best, but life is a daily struggle. Unable to work because there’s no one else to look after her children, she’s entirely dependent on the welfare state. There’s never enough money to make ends meet, and the apartment block she lives in is a site of almost Dickensian squalor: the stairwells are “smelly with a thick lavatorial stink,” the trash chutes are blocked and overflowing, and the apartments themselves are damp and poorly heated, the cupboards all “carpeted” with mildew. It’s a world rarely brought to life on the page with the candor and intensity of firsthand experience. “She, an African woman with five children and no husband, no job, and no future, was just like most of her neighbours—shiftless, rootless, with no rightful claim to anything. Just cut off … none of them knew the beginning of their existence, the reason for their hand-to-mouth existence, or the result or future of that existence. All would stay in the ditch until somebody pulled them out or they sank under.”

Upon learning that Emecheta had written up episodes from her life, a friend suggested she try sending them to Richard Crossman, then-editor of the New Statesman, Britain’s socialist paper. Emecheta typed up a few “Observations” and began sending one to Crossman every Tuesday (the day she visited the post office to collect her weekly family benefit payment). After a few weeks, she heard back, and he began printing her work as a regular column. This led to interest from publishers and agents, and soon Allison & Busby published In the Ditch—the collected columns turned into a novel. This was the beginning of Emecheta’s long and acclaimed writing career. By and large the reviews were excellent, but some critics wondered how a supposedly well-educated woman found herself in the ditch in the first place. These questions, Emecheta explains in her autobiography Head Above Water (1986), motivated her to write a prequel: Second-Class Citizen (1974).

Although Second-Class Citizen begins with Adah’s life in Nigeria—recounting her school days, her marriage, and the birth, shortly thereafter, of her two eldest children—the story proper is about her first years in England. In it, the trials and tribulations in Adah’s personal life—the birth of three more children, in quick succession, combined with her husband Francis’s neglect of his family, both financially and emotionally, along with his increasingly abusive behavior—are set against the endemic racism (and to only a slightly lesser degree, the sexism) she has to contend with in sixties London. The fact that Second-Class Citizen remains in print while In the Ditch has fallen by the wayside suggests that we’re perhaps more comfortable recognizing Emecheta as a writer who chronicles the immigrant experience than one who’s writing about what it’s like to be a woman living on the very bottom rungs of society.

When Emecheta died in January of last year, she had authored nearly twenty novels, and a host of plays and TV dramas. She was one of the very first black women to write for British TV, and one of Granta’s now-famous 1983 Best of Young British Novelists. Emecheta’s writing career was littered with the glass of broken ceilings: her 1982 novel Destination Biafra, for example, was the first published female perspective on the Nigerian civil war. In something of a departure from her earliest work, as her career went from strength to strength she was increasingly drawn to writing about postcolonial Africa, and in particular the villages of Ibusa in Eastern Nigeria from whence her family originally hailed. As such, today she remains best known as a chronicler of the country of her birth and her own distinctive heritage.

There is, however, also an important place for In the Ditch (and Second-Class Citizen) in the oeuvre of British working-class writing. Originating with the so-called angry young men whose novels, plays, and film scripts examined the sociopolitical struggles facing the poorest members of postwar British society, it’s a movement that traditionally lacked female voices. Though Emecheta always referred to her first two books as her “documentary novels,” they are rarely mentioned in this context.

*

Born Florence Onyebuchi Emecheta in 1944 in the Nigerian city of Lagos, her railway-worker father died when she was only eight, and her uneducated seamstress mother only wanted to see her daughter marry well. Emecheta, however, had other plans. She saved herself from an early marriage by taking—in secret—the scholarship exam for a place at the prestigious Methodist Girls’ High School. And, although she married Sylvester Onwordi and quickly bore him two children when she finished school at sixteen, she also procured a sought-after job at the American Embassy, which paid a very impressive salary. Her plan, however, was to emigrate to the United Kingdom. As she recalls in Head Above Water, her father always spoke of the UK in “hushed tones wearing an expression as respectful as if it were God’s Holiest of Holies,” and Emecheta wanted to make him proud by making it big there herself. In 1962, shortly before her eighteenth birthday, she and her two children sailed for Liverpool, on first class tickets courtesy of Emecheta’s hard work, where Onwordi (who’d gone on ahead) was waiting to take them to their new life in London.

What greeted Emecheta was a far cry from the promised land she’d imagined. As she explained in a British TV interview in 1975, she, like many others, had been “brainwashed” into thinking of England as “the United Kingdom of God.” Emecheta’s education, which had afforded her both respect and riches back in Lagos, was considered irrelevant in London. Here she was judged first and foremost by the color of her skin. Many landlords refused point-blank to rent to black tenants, and those that did offered only the most squalid rooms in slum housing.

Emecheta’s first few years in London were an uphill battle. Onwordi felt no responsibility to provide for his growing family, nor was he prepared to do any of the domestic labor, thus forcing his wife to be the breadwinner while also giving birth to another three children, for whom she had to care. At the same time, Onwordi became increasingly cruel and violent. She eventually left him—the final straw was when he burnt her first manuscript, a novel titled The Bride Price, which luckily she later went on to rewrite and publish. By the mid-’60s, Emecheta was a twenty-two-year-old single mother of five. When her youngest child was ten months old, the council rehoused the family in Montague Tibbles House, a large block of public housing in Kentish Town. This is the world she brings to life so vividly in In the Ditch.

*

When, in the seventies, Emecheta was wondering whether anyone would be interested in reading about her life, her time in Pussy Cat Mansions—the name she gives the estate in In the Ditch—was behind her. Finally condemned as unfit for human habitation, the residents were rehoused elsewhere. Emecheta and her children were allocated a modern maisonette in the upmarket neighborhood of Regent’s Park instead. Emecheta was also, by then, studying for a degree in sociology. She had always wanted to be a writer—in her autobiography she recalls that when she unselfconsciously announced her ambition to her grade-school class, she was punished for what her teacher saw as shamefaced pride. Regardless of which, she never abandoned her dream. Yet, rather than look to her imagination for inspiration, she now took that age-old piece of advice and wrote about what she knew. “The more I went into sociological theories,” she explains in Head Above Water, referring to her studies, “the more I could find their equivalent or what I termed their interpretation in real life. My life at Pussy Cat Mansions only a few months back could be regarded as ‘anomie’ or classlessness. I found I could relate my lack of any hope for the future and near personal despair to the same concept. Then why didn’t I write about that, and not the romantic happy-ever-after story that my first draft of The Bride Price had been?”

Emecheta had long been a voracious reader; her first jobs in London were working in public libraries. She was particularly inspired by books like Nell Dunn’s Poor Cow (1967), which follows the escapades of twenty-one-year-old Joy, a bleached-blonde single mother who’s left to make her own way in the world when her husband Tom is sent to prison, and Monica Dickens’s One Pair of Hands (1939) and One Pair of Feet (1942), which chronicle, respectively, the author’s experiences as a cook during the thirties and then as a nurse during the Second World War. If these women could write popular, well-received works based on their own lives, why couldn’t Emecheta do the same? As she puts it in her autobiography, “I decided to start writing again about my social reality.”

When In the Ditch opens, Adah and her children are living in rented rooms infested with rats and cockroaches. Adah has tried complaining to her landlord—a fellow Nigerian, who’s so affronted he takes to practicing juju in an attempt to scare her out of the house. It’s not that Adah doesn’t believe in it, “juju mattered to her at home in Nigeria all right,” but she feels safe enough ignoring it here in England, where it’s “out of place, on alien ground.” Adah continually resists the limitations projected on her by both Nigerians and the English. As she points out early in her story, “Ibo people seldom separate from their husbands after the birth of five children. But in England, anything could be tried, and even done. It’s a free country.” There’s no small irony in this final statement.

In the Ditch is as much a story of disappointment as it is tenacity. It doesn’t take Adah long to realize that she’s a lot less independent than she had hoped. Carol, the estate’s on-site family adviser, immediately starts poking her nose into Adah’s life. She tells Adah that she can’t leave her children alone at home while she goes out to work, or to college at night (though it is in Carol’s power to arrange a babysitter to help Adah some evenings). Adah’s exasperation-tinged gratitude is surprisingly refreshing:

That was one of the things Adah did not like about these white-coated females who called themselves social officers. They were bloody well too patronizing. All right, she had pointed out that Adah was wrong in leaving her kids in the evenings—why make a meal of it? […] Adah would have to swallow her pride as a woman, her dignity as a mother, and let Carol help her. She did not like to accept the help, but she had no choice.

After Carol’s admonition, Adah regretfully gives up her job as an administrator at the British Museum. “That,” Emecheta writes of her fictional alter ego, “closed her middle-class chapter. From then on, she belonged to no class at all. She couldn’t claim to be working class, because the working class had a code for daily living. She had none. Hers was then a complete problem family. Joblessness baptized her into the Mansions society.”

One of the bleakest elements of life in the ditch is the violence against women. Unhappy husbands don’t think twice about taking their frustration out on their wives. “The police could do little for a beaten wife,” Emecheta writes, “Sometimes it seemed that matrimony, apart from being a way of getting free sex when a man felt like it, was also a legalized way of committing assault and getting away with it.” Here, as on many other occasions, Emecheta is quick to point out the double standards between the working and the middle classes. “How many middle-class women would welcome a penniless drunkard pouncing on her in bed, just like an animal, simply because he owned her?” Adah asks astutely. Later in the novel, when she’s struck down by a particularly nasty illness and Carol insists on calling the doctor, the patient is left fretting she’ll be judged a slattern: “Adah crawled into bed, not to rest but to worry! Call the doctor into a flat in this condition! The floor had not been swept for two days. Kids’ litter cluttered every corner […] She wished she had been white and middle-class for then there would have been no need to worry—the doctor would have ‘quite understood.’ ”

The ditch is a world that’s unfairly stacked against women. “Fancy men,” as boyfriends are called, strictly aren’t allowed. If a woman is seen regularly with a man, the dole people start asking questions, assuming he’s helping her out with extra money, which they then want to subtract from what they’re giving her. As such, the women aren’t just poor, “they had to be sex-starved too. Their chances of marrying or remarrying were reduced almost to nil.” Unwanted babies are actively discouraged, yet as Adah knows full well, the morals of a middle-class office secretary aren’t subject to the same scrutiny: “The trouble with the system on this issue was that no one knew where the definition of respectable spinster ended and that of prostitute began. Also, with the popularity of the Pill, the diaphragm, contraceptive jelly and free abortion, how could it be necessary for society to be so inhumane?”

Although romance and sex doesn’t figure in Adah’s story—her priority is making an independent life for herself and her children—Emecheta is well aware of how important it is to others:

To most of these women sex was like food. Love was dead, except the maternal love they naturally had for their kids. To be deprived sexually, especially for women in their twenties who had once been married, was probably one of the reasons why places like the Pussy Cat Mansions were usually a fertile ground for breeding hooligans and generations of unmarried mums.

The Swinging Sixties were not quite as libertarian as we like to think. There’s a haunting episode in Second-Class Citizen when Adah, twenty years old and already the mother of three, tries to get a prescription for birth control only to find that she needs her husband’s permission; legally she’s not allowed any agency when it comes to her own fertility. It’s easy to read about the horrendous ways in which Francis treats his wife and deplore the position of women in Nigerian society, but life isn’t much better for women in the UK, especially not those living in poverty who “were always too ignorant or too frightened to ask for what they were entitled to.” The family adviser is supposed to be there to help empower these women, but more often than not she leaves them feeling all the more disenfranchised: “People like Carol were employed to let them know their rights, but the trouble was that Carol handed them their rights, as if she was giving out charity.”

*

Though racism figures prominently in Emecheta’s two early novels (“A black person must always have a place, a white person already had one by birthright,” is something Adah quickly learns), In the Ditch brings sexism and classism into equal focus. Though Emecheta never called herself a feminist, everything about the way she lived her life, and wrote about women, indicates that she was. One of the most striking elements of In the Ditch, for example, is the sense of community and solidarity that exists between the women on the estate, often regardless of their racial or ethnic differences. Emecheta was a woman of unparalleled independence, drive, and ambition, who wouldn’t let any man tell her what she could or couldn’t do.

In the last few years, there has been growing awareness across the publishing landscape that the industry has not done enough to foster and promote working-class writers. There’s no better time for us to rediscover the intersectional portrayal of poverty chronicled in In the Ditch. Emecheta fought so valiantly for the right for her story to be heard, it deserves to reverberate through the decades.

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, the Financial Times, The New York Times Book Review, and Literary Hub, among other publications.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2UcZzTO

Comments

Post a Comment