During my last two years of college in Chicago, I rode downtown by commuter train a few times each week. The trip took about 40 minutes, and I always brought a book to pass the time.

I read most of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain on the tracks between the Loop and the Davis Street stop. I paged through The Satanic Verses that way too. These were strange book choices, but I was a strange reader. I never felt like I had read the right books. Everyone else seemed to have read everything. I was so far behind I had no idea where to start. I had hunger, but no sense of taste.

I read most of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain on the tracks between the Loop and the Davis Street stop. I paged through The Satanic Verses that way too. These were strange book choices, but I was a strange reader. I never felt like I had read the right books. Everyone else seemed to have read everything. I was so far behind I had no idea where to start. I had hunger, but no sense of taste.

I certainly got no guidance from what other people on the train were reading. My fellow riders seemed to subsist on the Trib or Wall Street Journal alone. No novels other than the occasional Scott Turow or John Grisham. This was the golden age of the courtroom potboiler. I didn’t understand the priorities of these people whose lives were swarmed with mortgages, kids, and 401(k)s.

In 1998, I came to New York for graduate school, and at once I felt as if I’d found my people at last. I loved how so many people read books on the subway. Not just bestsellers, either. Novels, biographies, poetry collections. Books for people who loved reading.

To pay my bills, I got a job downtown at the Seaport. Once again, I was riding a train for most of an hour a few times a week. Nearly every day I would see a person reading a book that I had on a class syllabus, or a title from my own personal reading to-do list. New York felt like a place I knew, even though I didn’t really know it yet. The covers of books I recognized would stand out like friendly faces—well, hello, Gabo! What’s up, Woolfie? I see you’re a thing they carried, too, Mr. O’Brien!

Because I wanted so much to be a writer in those days, I spent many hours every week at the many bookstores of Manhattan. I bought used books because I couldn’t afford brand new ones. I was always waiting for a new release that I really wanted to show up as a remainder or as someone else’s cast off. If you want something that you cannot afford badly enough, then the packaging itself becomes an object of desire, and I began to be able to identify a book that I wanted after just the barest glimpse of its cover.

My favorite book covers were Vintage International paperbacks; their stately design, metallic hues, and dark tones were so lovely and pure. I would pick up a new author just because of the Vintage colophon. This was how I met Julian Barnes and William Maxwell. They had the right kind of references.

As it so happens, on a crosstown bus many years later, I fell into conversation with a woman who was the purchasing editor for Vintage International. I couldn’t find the words to express my gratitude to her; later, when she got off at her stop, I resisted the urge to ask for her email address. I didn’t want to give her the wrong idea.

Even after I finished graduate school, I still carried a book to the office each day. (In this way, I told myself I was different from those commuter train riders in Chicago years earlier.) Sometimes, at work I’d put the book face down on my desk, but usually I’d leave it out in the open: not to parade what I was reading but as a kind of invitation to anyone who wanted to talk books.

One winter, a colleague stopped by every few days to see how far along I’d gotten in War and Peace. Eventually, he began to offer up his own daily updates on his journey through books like The Count of Monte Cristo and The Killer Angels. I learned that he was a one-time history major who got swallowed up by the corporate world and was trying to find his way out.

One winter, a colleague stopped by every few days to see how far along I’d gotten in War and Peace. Eventually, he began to offer up his own daily updates on his journey through books like The Count of Monte Cristo and The Killer Angels. I learned that he was a one-time history major who got swallowed up by the corporate world and was trying to find his way out.

Shortly before I got married, I was transferred from the office at the Seaport to the corporate headquarters out in Newark. Once again, I found myself on a commuter train each day. My friends would grimace when I told them about my daily commute. To reassure them that it wasn’t terrible, I pointed out that I had time to read.

Smartphones and e-readers made their debut while I was commuting to Newark. I tried this out one evening when I downloaded The Time Machine onto a first-generation iPad. At the time, I was sitting in bed while my wife slept, and I needed no lamplight because the screen was illuminated. This pleased me at first. But as I read, I realized that the tablet weighed just a fraction too much; it pulled gently at my fingertips, tugging me back to the real world more than a physical book.

Smartphones and e-readers made their debut while I was commuting to Newark. I tried this out one evening when I downloaded The Time Machine onto a first-generation iPad. At the time, I was sitting in bed while my wife slept, and I needed no lamplight because the screen was illuminated. This pleased me at first. But as I read, I realized that the tablet weighed just a fraction too much; it pulled gently at my fingertips, tugging me back to the real world more than a physical book.

The technology for e-readers has improved greatly since then. I read more digital books than physical ones now. I don’t feel quite right about it. But I love the convenience and simplicity of reading via Kindle. I opted for a digital copy of Ian McEwan’s Nutshell rather than a print copy because I couldn’t wait to start reading for long enough to find a bookseller.

The technology for e-readers has improved greatly since then. I read more digital books than physical ones now. I don’t feel quite right about it. But I love the convenience and simplicity of reading via Kindle. I opted for a digital copy of Ian McEwan’s Nutshell rather than a print copy because I couldn’t wait to start reading for long enough to find a bookseller.

For years, I disliked the modern Penguin paperbacks with their serif fonts, text leading, and paper-bag beige pages, all wrapped up in a gaudy orange package. This problem has vanished in the age of the Kindle, too. I can change the font for my digital copy of Disgrace with an almost appalling ease.

For years, I disliked the modern Penguin paperbacks with their serif fonts, text leading, and paper-bag beige pages, all wrapped up in a gaudy orange package. This problem has vanished in the age of the Kindle, too. I can change the font for my digital copy of Disgrace with an almost appalling ease.

My complaint about digital books is this: They are mere ghosts, capable of possession, but never tangible or real. I suspect that people still read great novels on the subway, but I can’t tell; it looks like everyone is just staring at their phones. No one at work asks what I’m reading. There’s no book on my desk.

The virtual bookshelf on my Kindle is a list of titles that I have read but never held. These books are just ideas, abstractions, nothing less, nothing more. And ideas are grand, to be sure. But printed books are not just ideas. The print books that line the shelves in our home are solid artifacts, and their shapes describe the shape of my life.

A few years ago, I wrote an essay about flipping through my books and cataloging all the objects that I found between the pages. The ranks of books have not grown as much as I would have thought since then. It feels sometimes as if my book collection is a memorial to my past, rather than a collection of ideas that I can browse whenever I want. Recently, when I found myself unemployed for a stretch of time, I set about alphabetizing all the books. It was soothing to correct the placement of certain authors; to gather up all of Camus’s thin works in one stand; to set Joan Didion and E.L. Doctorow beside each other, as if at a cocktail party. I will never need to organize the titles of my virtual bookshelf. They are never out of order.

Understand, I come here not to praise too much the smell of paper glue or how the printed page glows under the light of the sun. I come here knowing the printed book is dead, or nearly so. I will continue to buy fewer and fewer print books, just like everyone else. But there are moments when I must resist.

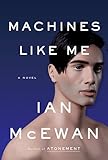

I placed an order last week for Ian McEwan’s next novel, Machines Like Me, which comes out in April. A print copy will be delivered on the day the book comes out. I look forward to carrying it around the city with me. Apparently, the novel is about artificial intelligence and the tension between the material and digital worlds that we all inhabit. Perhaps you’ll see me reading it on the train.

I placed an order last week for Ian McEwan’s next novel, Machines Like Me, which comes out in April. A print copy will be delivered on the day the book comes out. I look forward to carrying it around the city with me. Apparently, the novel is about artificial intelligence and the tension between the material and digital worlds that we all inhabit. Perhaps you’ll see me reading it on the train.

Image credit: Unsplash/Anastasia Zhenina.

The post The Ghost in My Hands: On Reading Digital Books appeared first on The Millions.

from The Millions https://ift.tt/2IGMdOn

Comments

Post a Comment