I read like a buzz saw cuts wood. A book a day is not unusual, and my discard pile is always bigger than the unread pile. Because new books are expensive, I buy my books online, at Goodwill, and at library sales. I seldom have to pay more than a few dollars.

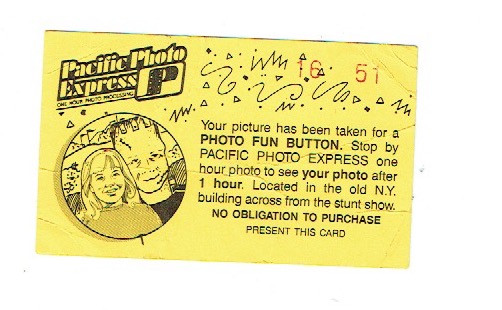

In the past few years I have discovered an added benefit, besides not bankrupting myself, to acquiring books secondhand. Many of the used books I buy have something left inside of them by their former owners. Here are some things I have found: a Seattle traffic ticket for jaywalking, the luggage slip for a first class flight to Paris, to-do lists with some very curious items like “pick up the whip” or “explain cremation.” Often I find ticket stubs (Hamilton!). Once I found a check fully made out for $375.15 dollars that was never given away, and just today I found a yellow card from Pacific Photo Express that offered to transform my images into a “photo fun button.” I am not sure I want such a pin: the illustration shows a creepy little girl getting cozy with Frankenstein’s monster. I can’t quite imagine the right occasion on which to wear that.

I no longer get excited when I find something as simple as a grocery store receipt, but I still try to match the book with what the person eats. Twelve boxes of red Kool-Aid in an Oliver Sacks book on migraines was simply confusing, but cage-free eggs seemed appropriate in a book about prison reform.

In my books I have found printouts for stuffing recipes, a list of starred AA meetings, and “The Star Spangled Banner” written in the spidery hand of someone either very old or very young. Occasionally I will find a disturbing, cryptic note. In Susanna Kaysen’s The Camera My Mother Gave Me (a literary lament to the author’s chronic vaginal problems), a slip of paper read “Please stop me”.

Sometimes the inserts are better than the books themselves. Photographs are the rarest finds. They are often faded Polaroids of a blurry vista or a pre-selfie-era portrait. More often than not, the portraits are unflattering, which may be why they were left behind in a book. Also left behind are participation ribbons for a sixth-grade sporting event, and a third-place ribbon from a small-town dog show.

There must be some higher astrological power that guides strange books into my hands. When I was a student at Yale in the seventies, I got a summer job in the basement of the Sterling Library. Sterling is an awe-inspiring piece of classical architecture, but the basement was just a basement. It had no windows. The florescent lighting flickered overhead and it wasn’t air-conditioned, even during the hottest months. Still, I was happy to have a library job. I thought I felt comfortable around books and readers. By the end of summer, I had changed my mind. I had brushed up against the dark side of libraries.

Every morning at 9:30 AM, three older ladies and I waited for a rolling metal pallet of books to be delivered. There were about a hundred books on the trolley. We were each given a place at a long work table, and at each place setting were five gum erasers and a paintbrush. There was very little office chitchat. The basement was sobering; it was not a place to have fun.

If I had a job title, it might have been “book cleaner,” but that does not describe the odd nature of the work.

It is a strange but true fact that people who lurk around the library stacks are often disrespectful of the books. In fact, they apparently use the books as targets for their rage. This is a polite way of explaining that my basement job was to clean human effluvium out of the books.

Students often blew their noses in the pages of books. Down in the basement, we were not offered rubber gloves but it would have been a good idea. More than a few books had wads of semen between the pages. The books that were inseminated were not risqué books. They were dry as a bone: studies in economic theory or eighteenth-century literary criticism. I wanted to know how these boring tomes had brought someone to climax. Maybe it was a desperate attempt to inject life into dead pages.

I am not nostalgic for my days as a basement book cleaner. Although the discount reading material I buy often has humanizing touches left between the pages, I have never come across a book as soiled as the ones at the Yale library.

I’m often tempted to send off one of my just-read books with a mysterious message tucked inside, like a note in a bottle washed up on shore. The main reason I haven’t done this is because I have nothing to say. “Hi” and “Hello” are beyond lame. Even my detritus is boring—all my photos are on my computer, and if I turn over my handbag only an empty Tootsie Roll wrapper falls out. I’m a verbose writer, but I’m stymied at the notion of writing a note to leave in a book. I draw a blank, I get stage fright, I am paralyzed by the task.

It reminds me of when I got my first diary, when I was eight years old. Looking back at it now, every page is the same: “Dear Diary; Nothing much happened today.” Maybe my life is a big bore. I don’t need anyone to “stop me,” I do not need to “pick up the whip” or “explain cremation,” and, really, who wants a photo fun button? I suppose I can scribble “Nothing much happened today,” on the back of a bank-deposit slip, and, sadly, that would still be true.

Jane Stern is the author of more than forty books, including, most recently, Confessions of a Tarot Reader. With Michael Stern, she coauthored the popular Roadfood guidebook series. The Sterns recently donated forty years of archival materials to the Smithsonian museum, documenting the atmosphere, stories, and history of various restaurants, diners, and regional food events.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2tGtYP2

Comments

Post a Comment