Larissa Pham’s monthly column, Devil in the Details, takes a tight lens on single elements of a work, tracing them throughout art history. In this installment, she focuses on women in bathrooms.

The door of my childhood bedroom didn’t have a lock on it, so I spent a lot of time in the bathroom. Every human wants privacy, but no one more than a teenage girl. Though I ostensibly shared the bathroom with my little brother, I claimed it as my domain. I spent hours reading on the tiled floor, my body bracketed between the sink and the door. In my memory, it’s a slightly steamy, always warm, watery place—but I never spent that much time in the bath. If I wasn’t reading or sulking after a fight with my parents, I was performing those charmless beauty rituals teenage girls are so fond of—shoving my A-cup breasts together trying to make cleavage magically appear in the mirror; waxing my legs with a kit I’d surreptitiously tipped into the family shopping cart; dyeing the tips of my hair hot pink. Manic Panic spotted half my towels; menstrual blood stained the rest. In the bathroom—my bathroom—I lounged, I cried, I sat on the edge of the empty tub, my two thumbs laboriously T9-texting my friends.

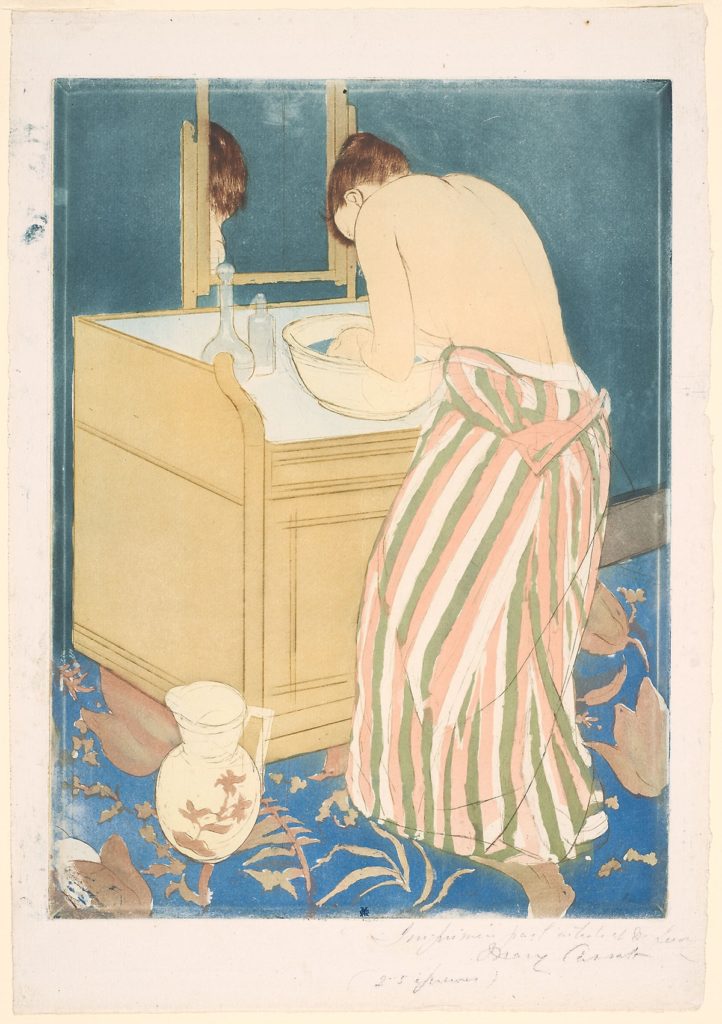

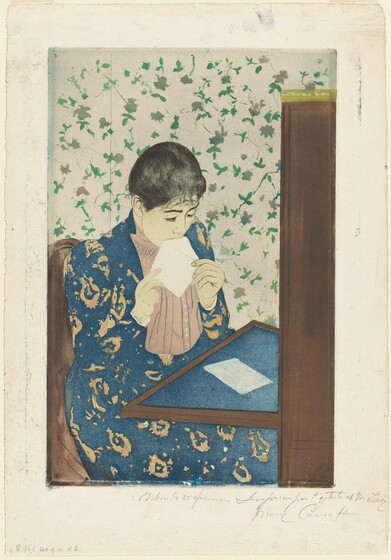

Last summer, my roommate brought home a framed print of a woman standing at her toilette. She found it for five dollars at a yard sale in the Hamptons and purchased it for the Dutch blue frame, but I liked the elegance of the print—a replica of a Mary Cassatt drypoint and aquatint, Woman Bathing, from 1891. In the composition, a woman bends over a basin, one hand submerged in water, the other at her brow. She is nude from the waist up; her dress is rendered in appealing, nearly abstract stripes, and the shape of her skirt blocked out in solid, pastel colors—sage green, snow white, sunrise pink. On the floor is a flowered water pitcher, and the ground is similarly patterned with ferns and flowers in warm gray and thinned-out royal blue. The image is modest—we see only her smooth back, the faint shape of her breasts—and the mood is one of quiet intimacy, a peek into one woman’s private world. Though Cassatt’s subject stands opposite a mirror, her face is hidden from us. Her expression is caught in the private, unreadable space between her body and the mirror. I love this most—that her image is doubled and therefore doubly hidden from us. The rectangle between her face and her reflection becomes a chamber of endless possibility: What thoughts run through her mind? The flowered ground rises up to meet her.

Cassatt’s drypoint has a clear antecedent in the ukiyo–e woodcuts of Edo-period Japan. Emerging as a genre in the seventeenth century and peaking in popularity in the late eighteenth, ukiyo-e were pictures of the “floating world”—the pleasure-driven milieu of the underclass bolstered by the economic growth Edo (now Tokyo) enjoyed when it became the seat of government power. Ukiyo-e woodcuts frequently depicted landscapes, beautiful women, and scenes from history and folklore; there was also a school devoted to erotic art, called shunga. As the form developed, the ukiyo-e images favored by the members of the floating world came to depict the activities of the consumers themselves in hedonistic, erotic scenes, as well as quieter, more poetic renditions of daily life—scenes of women dressing and bathing, for example, or applying whitening powder. Characterized by delicate outlines filled with floods of color, with dramatically foreshortened, asymmetrical compositions that flattened the picture plane, ukiyo-e paintings were popular with the merchant class, created to be economical options for decorating one’s home and affordable souvenirs for tourists.

In 1890, an exhibition at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, organized by art dealer Siegfried Bing, gathered hundreds of ukiyo-e prints from artists such as Utagawa Hiroshige and Katsushika Hokusai. Ukiyo-e prints and other Japanese art objects had made their way to Europe throughout the 1800s, primarily in the hands of Dutch traders, and Japan exhibited for the first time at the World’s Fair in 1867, inspiring the artistic movement known as Japonism. But Bing’s now-legendary exhibition marked a turning point in the creative dialogue between Japan and Europe. Many artists—Edgar Degas and Camille Pissarro among them—visited the exhibition, and its impact would reverberate through the work of the Impressionists for decades. It was at the École des Beaux-Arts that Mary Cassatt became enchanted by ukiyo-e woodcuts, particularly the domestic scenes of Kitagawa Utamaro. The aesthetics of the ukiyo-e form are all over Woman Bathing, one of a series of ten prints Cassatt made in explicit homage to Utamaro in the months after visiting the exhibition. Though Cassatt used drypoint and aquatint rather than woodblock printing, the delicacy of the line, the simple floods of color, and the floating patterns of the image—the stripes of the skirt; the leaves and flowers of the ambiguous ground—all speak to the influence of the prints she viewed.

Cassatt’s depictions of domestic space distinguished her work from that of the other, predominantly male Impressionists. As a group, the Impressionists were interested in depicting daily life—backstage at the opera, for example, or scenes of nightlife, as in the work of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, another artist influenced by Japonism. Yet Paris in the 1880s wasn’t a particularly welcoming environment for a woman to wander around alone, and Cassatt found rich subject matter in the space where women were in control: the space of the interior. As an art-historical figure, Cassatt represents a kind of early feminist independence—a woman who chose an artistic career rather than motherhood, drawing upon her surroundings for material and depicting her subjects as having agency, despite the limited roles they were expected to hold in society.

The Mary Cassatt print of Woman Bathing hangs in my bathroom now, on the wall next to the sink. These days I have a bedroom door that locks, but I still spend a fair amount of time in this bathroom, too. Washing my face at night, my hands dripping sudsy water to the elbow; prodding at eruptions of hormonal acne on my chin, zooming in on flaws in the mirror. Some mornings I drag a brush-tip liner pen across my eyelids; most weeks I exfoliate with a Korean peeling gel. In the summer—and I know it should be all year round—I smooth Biore Watery Essence sunscreen onto my oily face, where it dries into a matte, velvety sheen. But most often, I find I’m not really in the bathroom to do anything at all. I’m just standing there, studying my face.

The bathroom is a private space; it’s also a liminal one. It’s where women go to become—to cleanse the body and put on the self in anticipation of the outside world. I have a softness toward the girl I was at fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, thinking about the woman she longed to transform into—the epilations, the padded bras, the long showers standing on one foot, maneuvering a pastel-pink razor, leg hoisted up. I’m kinder to myself and to my body now, but I still treasure the calm, potent space of the bathroom. It feels like a space where we can return to being unformed. When I stand alone in a bathroom, whether my own or that of a hotel or bar or a lover’s apartment, looking at myself in the mirror as I rinse my hands, I can’t say that it’s out of vanity, but curiosity: How did I get here? How did I become this way? I take a moment to become myself in the space between my face and the mirror, and then I open the door.

Cassatt’s model modestly turns away from us. Her dress has been unbuttoned to the waist; it falls in loose folds over her hips, turning her lower body into an abstract shape. Her body thus becomes divided into two distinct compositions, making Woman Bathing a perfect depiction of the liminality of the bathroom space. Here she stands, halfway between dressed and nude—she is between modes, between times of day, between one room and the next. Her back is toward us, rendering her vulnerable, but she’s safe where she stands, in the sensuous, private space of her toilette.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Cassatt’s contemporary, and a substantially more famous Impressionist, composed a series of lithographs, called Elles, in 1896, most likely inspired by ukiyo-e woodcuts (and perhaps by the work of Cassatt as well). The series depicted scenes of domestic life and intimacy between the women who worked at a brothel in Paris, whom hec frequently painted. Elles contains a lithograph of a woman bathing, too. The image is composed similarly to Cassatt’s, with the model’s back turned to the viewer, and one hand on the rim of a basin of water. Like Cassatt’s model, Toulouse-Lautrec’s bathing woman is nude from the waist up. Yet Toulouse-Lautrec’s depiction revels in the physicality of his model—he renders the cords of muscle in her arm that grips the basin; you can feel the weight of how she leans. Unlike the smooth, idealized back of Cassatt’s Woman Bathing, Toulouse-Lautrec’s model has wrinkles and folds in her skin; her full breasts hang heavy with their gravity. Where Cassatt’s bather disappears into herself, Toulouse-Lautrec’s model is revealed to the viewer—though her face is cut off, her breasts are reflected in the mirror.

Toulouse-Lautrec’s rendition of the genre emphasizes the bodily aspect of bathing, of becoming close to its elements—sweat, blood, excrement. This woman is a working woman, a woman of the world. Though Toulouse-Lautrec eroticizes her nude body, he also emphasizes her strength—I keep returning to the way her left hand firmly grips the rim of the basin, fingers curled. In this depiction, the bathroom becomes a different kind of space: a site of erotic charge mingled with stark pragmatism. Perhaps my youthful experience was more in line with Toulouse-Lautrec’s bathroom than Cassatt’s—the violence of the plastic razor, the vigor with which I scrubbed my acne-prone face, even the goriness of the tampons I wrapped in toilet paper and jammed in the trash can each month. (One can’t imagine Cassatt’s model bleeding, though she surely did.) Toulouse-Lautrec’s bather doesn’t float in space: She anchors it. She owns the room.

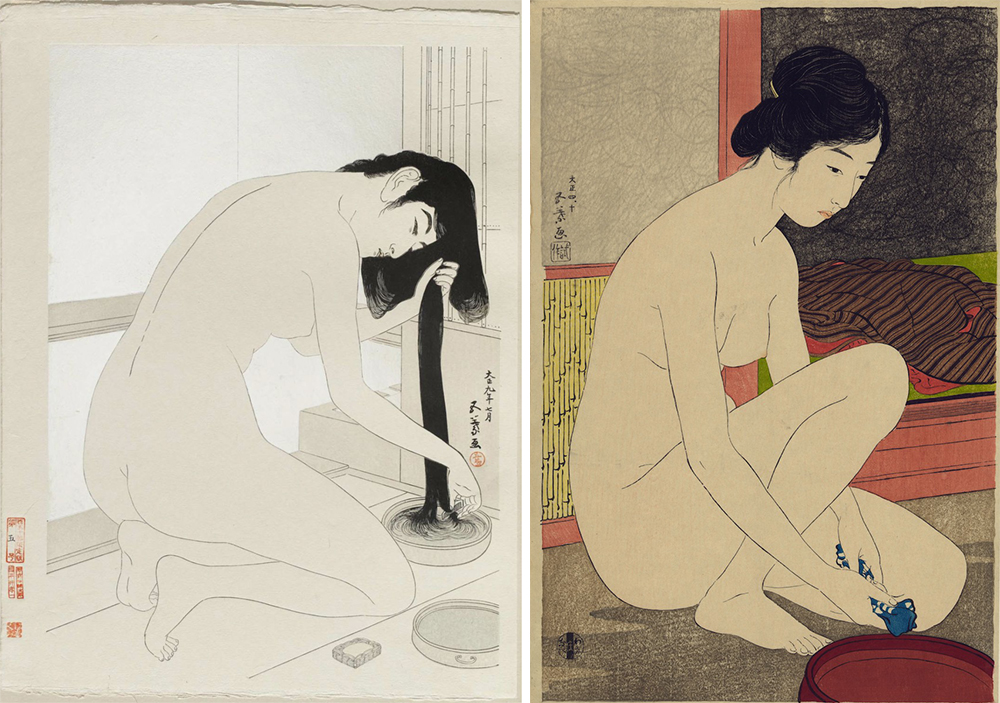

Hashiguchi Goyo. Left: Woman washing her hair, designed 1920, printed 1950. Right: Woman after her bath, printed 1915.

In 1920, thirty years after Cassatt’s drypoint, during the movement of shin-hanga (literally “new pictures”), a revitalization of the now old-fashioned ukiyo-e, the artist Hashiguchi Goyo designed Woman washing her hair (髪を荒う女, or Kami o arau onna). The piece was printed only decades later, posthumously, in 1950. Goyo’s career was cut short by health problems, and his insistence on high-quality printing meant that few original prints of his work remain. His prints are characterized by the delicate sensuality of his models—his women have soft, naturalistic bodies, their proportions appealing to his modern audience. Goyo’s bather is fully nude, and her face is turned toward the viewer. She wears a pensive, calm expression.

Goyo’s woodcuts invite us to admire the models, to delight in their bodies with our eyes. The woman washing her hair may not make eye contact with us—she doesn’t confront the viewer—but she isn’t ashamed, either. Goyo’s rendition of the uses the setting as a way to more overtly showcase the erotic nude form. The liminality of private/public suggested by Cassatt and Toulouse-Lautrec’s bathing women has given way to a wholly interior space—the door closed, the clothes folded on the floor. As viewers, we can choose to gaze desirously, or we can enter as confidants, fellow bathers in the space.

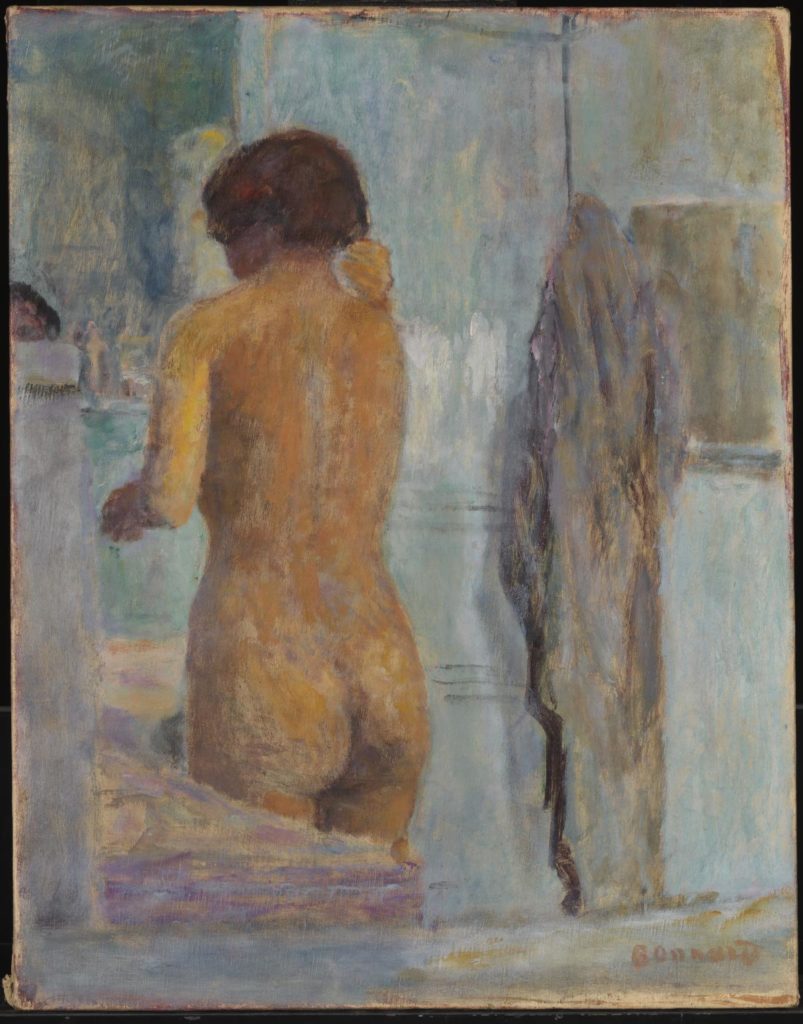

Pierre Bonnard’s nudes, composed around the same time that Goyo made his prints, and inspired by Japonism (as were many of his peers in the collective Les Nabis), also have a deep interiority. Bonnard’s bathrooms are hazily colored, post-Impressionist spaces—in The Bath, from 1925, a woman rests nearly completely horizontal in a tub, her skin dappled with blues, creamy yellows, and rose, shimmering beneath the water. Bonnard’s bathers, modeled by his lover (later his wife) Marthe de Meligny, are languid, their curvy, sensuous bodies backlit and painted in caressing strokes. Bonnard’s work is remarkable for his chromatic range—he used dozens of hues to represent the roundness of forms, making his paintings deeply sensory experiences.

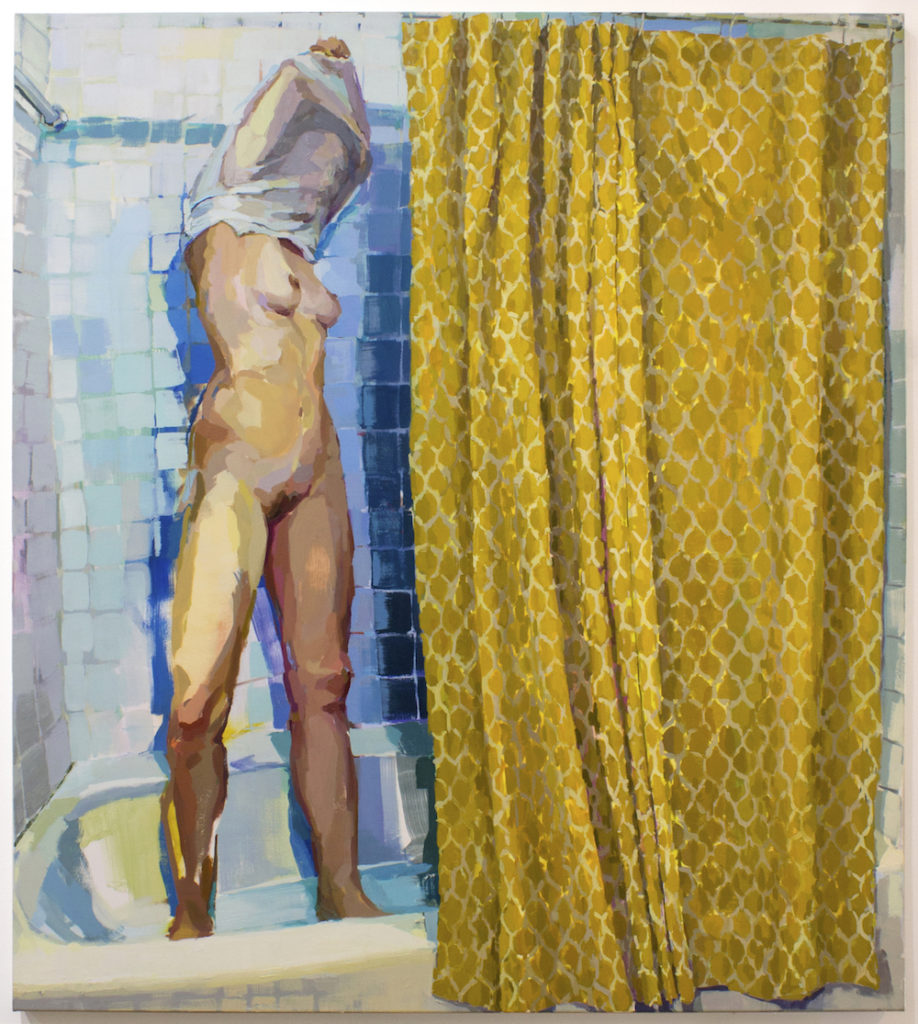

Some months ago, my friend Anna sent me a photo of a small, intimate painting by the artist Rachel Rickert. Rickert, a contemporary painter working in Brooklyn, depicts figures in intimate, domestic settings, with an emphasis on gesture and ritual. In Soft Boundaries (2019), now on view at Danese/Corey Gallery in Manhattan, a woman stands in a tub, arms over her head as she yanks off a semi-transparent T-shirt. The woman’s stance is wide, with the grounded, muscular weight of Toulouse-Lautrec’s model; her body is spackled with light—it strikes her exposed breasts, the bright plane of her thigh. One imagines a skylight above, a fluorescent light, a window.

Rickert’s twenty-first-century bather is in the act of exposing her body—the eye lingers on the planes of her torso, rendered in confident strokes, where light breaks across her form. In Rickert’s depiction, there’s the feminist independence of Cassatt and the physicality of Toulouse-Lautrec,; the open sensuality of Goyo and the emotional coloring of Bonnard. Her bathroom is an in-between space, too—the image is divided horizontally by the curtain, which hides and reveals. Like Cassatt’s bather’s, her face is hidden; though the viewer is invited to look at her body, the T-shirt, stretched over her head, protects her private internal world.

What strikes me most about Rickert’s bather is her agency: the control she has over the painting. Even the title, Soft Boundaries, alludes to how much we choose to let someone into our private space. And the most dominant element of the painting may not be the bather herself, but the golden curtain, shimmering with a pattern reminiscent of scales. Rickert’s bather chooses to reveal herself, to share her intimacy. But the curtain suggests that at any moment it can be pulled away.

Larissa Pham is a writer in Brooklyn.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2HMENI3

Comments

Post a Comment