Read our Art of Poetry interview with Lawrence Ferlinghetti in our current issue.

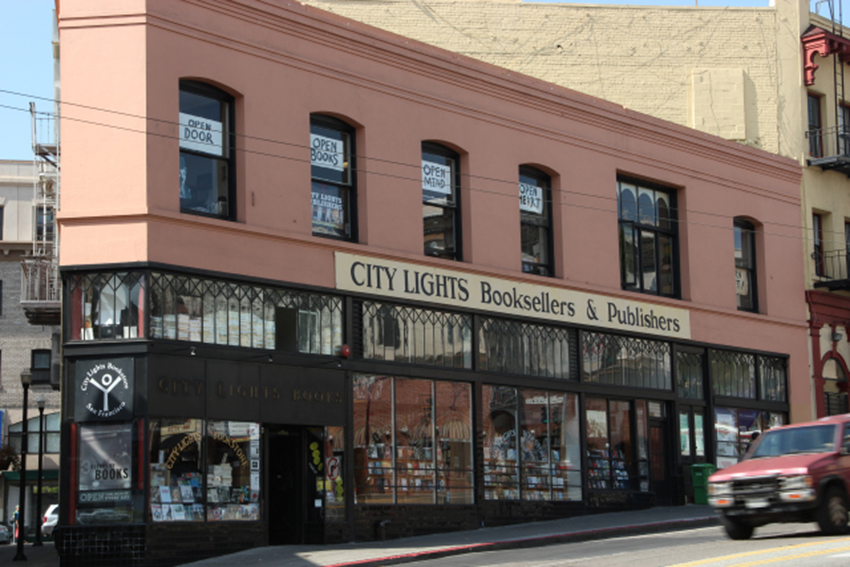

I hear the party at City Lights Books before I see it. The Beats, and their twenty-first-century torchbearers, are neither quiet nor sober. The bookstore is celebrating Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s hundredth birthday in an event open to all of San Francisco. A man with shoulder-length gray hair sits cross-legged on Columbus Avenue drinking Squirt and reading Mark Twain to himself. People step around him. Men with glasses sport boots that will never be polished. The air is thick with a blend of smoke from cigarettes and joints—there are no e-cigarettes, no vape pens in sight.

Poet Guillermo Gómez-Peña tells the assembled crowd that the hijos y nietos de Ferlinghetti have gathered to celebrate his century-old cumpleaños. The artist recounts first meeting Ferlinghetti, who was wearing huaraches and a bolo tie, in Mexico City. “It was 1975, mas o menos, and it was Mexico City, capital of the continental crisis,” Gómez-Peña says. In the following speeches we learn that Lawrence Ferlinghetti was everywhere: Nagasaki in ‘45, Havana in ‘59, Paris in May ‘68, and San Francisco before, during, and after. He stayed home on the first annual Ferlinghetti Day in San Francisco, but the streets filled in his honor.

Tucked between the stacks in the fiction section a graying gentleman in round glasses drinks from a flask. A layer of dust covers his fedora and a thin book of poems peeks out from the pocket of his army-green jacket. He snaps his fingers as Gómez-Peña reads: “Poetry is news / from the frontiers of consciousness.”

It’s a rare crisp and sunny San Francisco afternoon and City Lights has brought the Beats back to North Beach. The celebration meanders. Inside, the audience crowds together as poets read favorite Ferlinghetti poems. The PA system crackles. The poets stand on the mezzanine level; the people wind among the stacks. The crowd bends their necks trying to see the poets’ mouths move. The microphone fries Ishmael Reed’s baritone as he reads from “Tentative Description of a Dinner Given to Promote the Impeachment of President Eisenhower.”

News alerts buzz on phones: Mueller’s report did not provide evidence of collusion between the Trump administration and Russia. The audience cheers and claps as Reed reads out the last lines of the poem. The spirit of the crowd is unwavering. These are not the types to accept a verdict from on high, or to renounce hope.

Outside John Paul Carrabis II blows bubbles into the crowd gathered in Jack Kerouac Alley. He, too, has shoulder-length gray hair, and wears a Hawaiian-print shirt. One woman twirls among the bubbles, which pop on the back of my neck. The bubbles float out over a theater group midperformance. They play three selections from Ferlinghetti’s “Routines,” thirteen experimental plays written in 1955.

I spot a few teenagers watching the performance. They are dressed head to toe in black, and as they watch the old folks hoot and howl, they try not to smile. The performance ends when the Greek-style chorus pelts the lead actor with balloons filled with fake blood. He keeps singing, holding a golden frame in front of his body. They exit through the crowd in twelve-tone chant. No one seeks harmony. Red liquid runs between the paving stones in the alleyway.

Later, I find Richard Talavera, the man who organized the performance. The fake blood has dried hot pink on his button-down shirt. He tells me he wanted to perform all of the “Routines” but time was short and money nonexistent. He had called around and put together a troupe of actors and musicians willing to work for free. In the spirit of Ferlinghetti, there was no audition. He points to a circle of women beside us, one by one. “That’s my ex … That’s my ex … That’s my ex … That’s my ex … and that’s my sister,” he says.

Up Columbus, Carrabis blows bubbles at a Big B Bus driving by. “Hey, we have poetry here!” The tourists on the upper deck don’t wave back, but I imagine the weirdos of San Francisco make it onto someone’s Instagram.

“[Lawrence] created the structure for poets to howl,” Carrabis says to me. He performs the last word more than he says it: he tosses his head back and bellows as if imitating the call of a wolf to a full moon. He tells me how people would drink, write poems, and vomit with Charles Bukowski at Vesuvio Café.

At two in the afternoon, the waitress at Vesuvio Café balances cosmos and martinis on a plastic tray. The café is a time capsule. Glasses break and poets shout from the balcony. Younger folks in stiff clothes peek out at the activity below. Cosmic Ronnie gives me his business card: an eight-and-a-half-by-eleven sheet of paper that advertises one-of-a-kind guided tours of Manhattan. Ronnie considers himself from Greenwich Village even though he grew up in Long Island. His whole family does transcendental meditation. “Twice a day,” he says and taps his wrist. “We never miss.”

Ferlinghetti has described today’s San Francisco as “an artists’ theme park without the artists,” and I’d wondered if this event would feel as manufactured as a theme-park ride. I thought his birthday party might spiral into a set of curated attractions designed to provoke nostalgia. Instead, I met the kooks who remembered North Beach before the kids and the dogs took over. They treated the streets with the same wild abandon they had before their hair turned gray.

Read our Art of Poetry interview with Lawrence Ferlinghetti in our current issue.

Nina Sparling is a writer and audio producer based in California. She’s a master’s candidate at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2HUV64R

Comments

Post a Comment