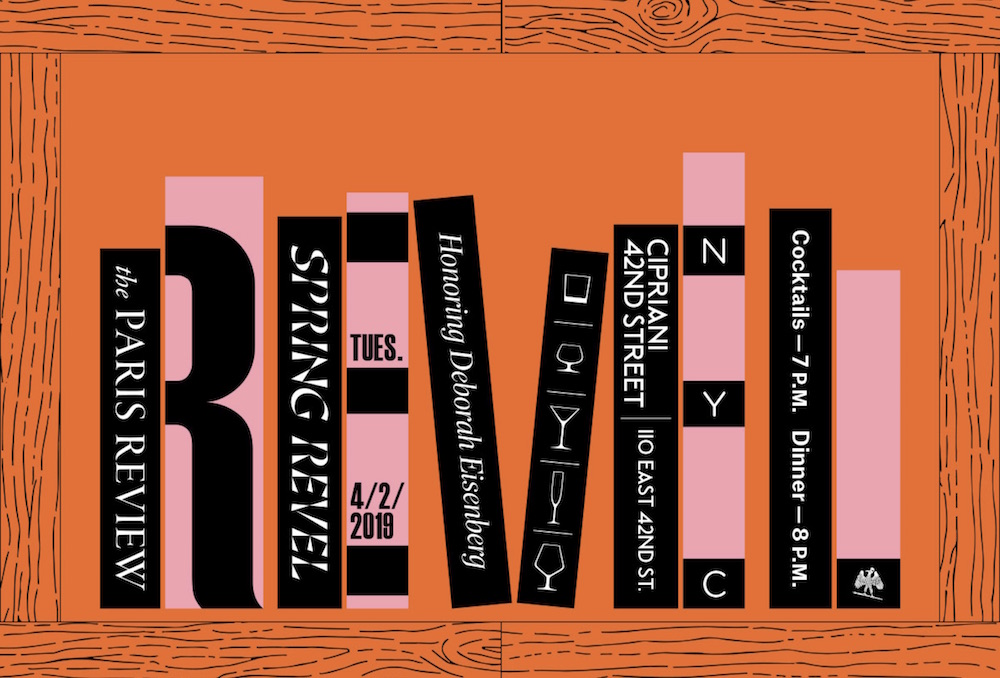

The Paris Review’s Spring Revel is less than a month away—tickets are still available here—and the editorial committee of our board has chosen the winners of two annual prizes for outstanding contributions to the magazine. It’s with great pleasure that we announce our 2019 honorees, Kelli Jo Ford and Benjamin Nugent.

Winners of the Plimpton Prize include Isabella Hammad, Alexia Arthurs, Emma Cline, Ottessa Moshfegh, Jesse Ball, and Yiyun Li; Southern Prize winners include David Sedaris, Vanessa Davis, Chris Bachelder, Mark Leyner, Ben Lerner, and Elif Batuman. The Review began awarding prizes to its contributors in 1956; here’s a full list of past recipients, including Philip Roth, David Foster Wallace, Christina Stead, Denis Johnson, Frank Bidart, and Annie Proulx.

The Plimpton Prize for Fiction is a $10,000 award given to an emerging writer published in our last four issues. Named after our longtime editor George Plimpton, it commemorates his zeal for discovering new writers. This year’s Plimpton Prize will be presented by the novelist Richard Ford to Kelli Jo Ford, for her story “Hybrid Vigor,” from the Winter 2018 issue. “Hybrid Vigor” focuses on the unforgettable Reney, a young woman struggling to find her way out of the adulthood she’s been dealt, living paycheck to paycheck. She manages a Dairy Queen, attends night school, and scratches out a life on a dwindling plot of farmland, where a calf and her prized mule, Rosalee, have just gone missing.

Kelli Jo Ford’s first book, Crooked Hallelujah, will be published by Grove Atlantic next winter. Her fiction has appeared in publications such as Virginia Quarterly Review and the Missouri Review, which awarded “Book of the Generations” the 2018 Peden Prize. She’s been a Native Arts and Cultures Foundation Fellow, an Elizabeth George Foundation Grant recipient, a Dobie Paisano Fellow, and Indigenous Writer-in-Residence at School for Advanced Research. She lives with her husband, Scott Weaver, and their daughter in Richmond, Virginia. She is a citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma.

The Terry Southern Prize for Humor is a $5,000 award honoring humor, wit, and sprezzatura in work from either The Paris Review or the Daily. It’s named for Terry Southern, a satirical novelist and pioneering New Journalist perhaps best known as the screenwriter behind Dr. Strangelove and Easy Rider. Southern was a driving force behind the early Paris Review, as is amply demonstrated in his correspondence. This year’s Southern Prize will be presented by the novelist and previous Southern Prize winner Elif Batuman to Benjamin Nugent, for his story “Safe Spaces,” from the Summer 2018 issue. “Safe Spaces” tells the story of Claire, a coke-addicted college dropout who hasn’t yet left town. With typical tenderness, Nugent chronicles Claire’s aimlessness as she couch surfs, attends the occasional campus function with her maybe girlfriend, and eventually finds the support she’s looking for in an unexpected place.

Benjamin Nugent’s stories have appeared in Best American Short Stories, Best American Nonrequired Reading, and The Unprofessionals: New American Writing from The Paris Review. His first collection, Fraternity, is forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Congratulations to Kelli and Benjamin—and to Deborah Eisenberg, who will receive the Hadada, our lifetime-achievement award—from all of us at the Review. We look forward to seeing you on April 2.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2ET9mt5

Comments

Post a Comment