In her new monthly column Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print and forgotten books that shouldn’t be.

When it was published in 1929, All Quiet on the Western Front, by the German World War One veteran Erich Maria Remarque, was an international bestseller. His blackly brutal account of life in the trenches touched a nerve with readers who were still reeling from the aftershocks of the Great War. Hoping to cash in on some of Remarque’s success, the following year, Albert E. Marriott, an enterprising London-based publisher who was new on the scene, approached popular children’s writer and journalist Evadne Price and asked if she’d be willing to write a spoof response about women at war. He had in mind a title — ‘All Quaint on the Western Front — and a pen name for her, Erica Remarks. Price had a talent for pastiche—she was the author of a popular series of girls’ stories which mimicked Richmal Crompton’s hugely successful Just William books—but she had no intention of making light of such a serious subject. Instead, she offered to write a realistic account of a woman’s experience in Flanders. In a bid for verisimilitude, Price relied heavily on the diaries of a woman named Winifred Constance Young, an Englishwoman who had served as an ambulance driver behind the front line. Price, ever the consummate professional, wrote quickly, and the novel was finished in only six weeks. Not So Quiet … Stepdaughters of War (1930) is a shockingly visceral and realistic documentation of the cost of the conflict written as the first-hand account of a woman ambulance driver. Hers is a world of “wounds and foul smells and smutty stories and smoke and bombs and lice and filth and noise, noise, noise […] of cold sick fear, a dirty world of darkness and despair,” as well as a shattering denunciation of the jingoism that kept the war-machine turning. Although last year marked the centenary of the end of the First World War, Europe once again teeters on the brink of a new era of incendiary nationalistic fervour. As such, a new generation of readers would do well to turn to Price’s novel. It’s as much a warning for our future as it is a reminder of our past.

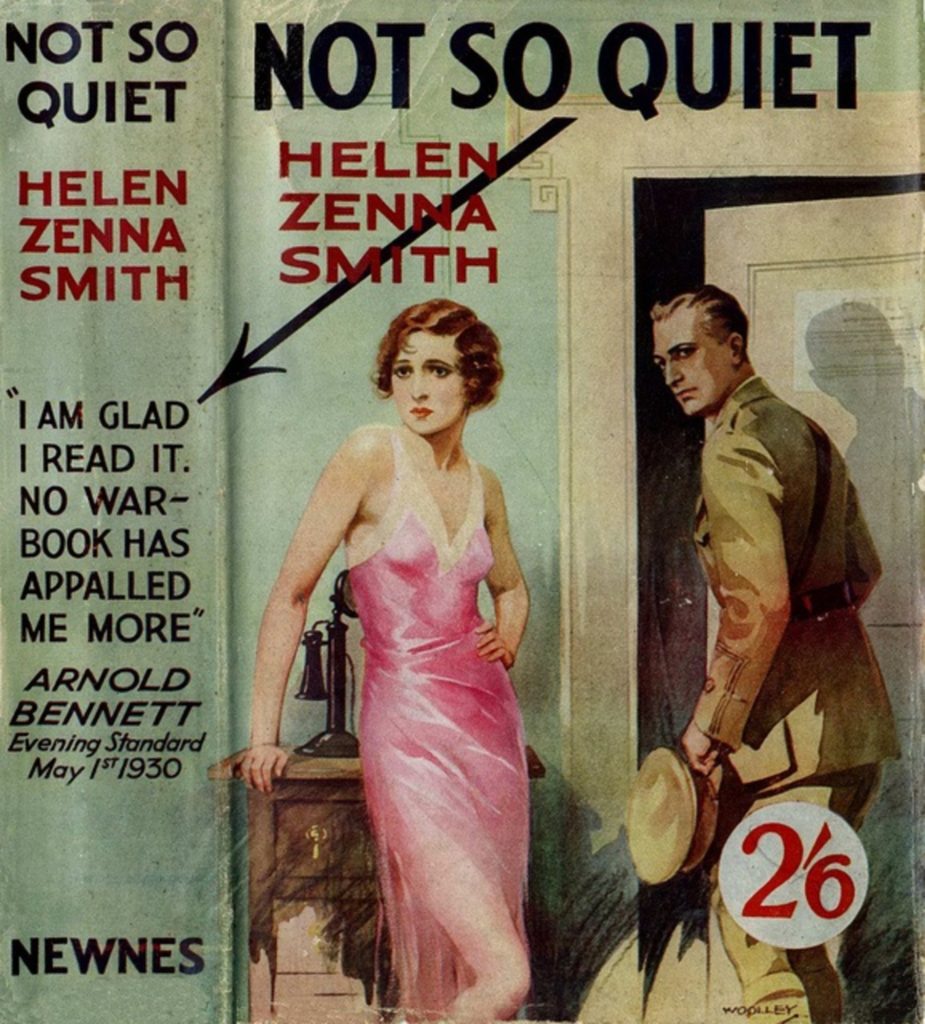

Not So Quiet was published under the pseudonym Helen Zenna Smith—the full name of the novel’s heroine, known as “Smithy” to her fellow combatants, and “Nell” to everyone else—which gave the impression that it was a work of autobiography, rather than fiction, and contributed to its success in an era when first-hand accounts of the war still sold strongly. This impression was further strengthened by the book jacket’s claim that this was “An honest, unsentimental, savage record of a girl ambulance driver in France.” This light deception was pretty vanilla for publisher Albert E. Marriott, who, it transpired, was actually just one of the many personas used by legendary confidence trickster Netley Lucas — but that’s a whole other story.

Some critics weren’t convinced. “A book to burn,” decried one, shocked by the unladylike contents. And yet, Not So Quiet quickly became a bestseller in Britain, replicating Remarque’s success. It appeared in serial form in Collier’s Weekly in the US, and was awarded France’s Prix Severigne, for “the novel most calculated to promote international peace.” Due to popular demand, Price—again using the nom de plume Helen Zenna Smith—went on to pen four consecutive sequels: Women of the Aftermath (1931); Shadow Women (1932); Luxury Ladies (1933); and They Lived With Me (1934). A victim of its own success, Not So Quiet is tarnished by its association with these unworthy, increasingly romp-like successors, none of which were able to match the powerful ingenuity of the original. The all-too-swift arrival of the Second World War curtailed the market for accounts of the First, and Price’s rejoinder lacked the immediate authenticity of enduring classics like All Quiet on the Western Front,. In spite of all its contemporaneous success, Not So Quiet disappeared into obscurity. And though Price wrote well over a hundred books (most of which were mass market romance paperbacks), plays, screenplays, and a broad assortment of journalism, from newspaper columns and horoscopes through war reportage, she slipped into obscurity as well.

*

Nell is a tender twenty-one years old when Not So Quite opens. She and her fellow ambulance drivers—“Tosh”, “the B. F.”, “Etta Potato”, “Skinny”, and “The Bug” as they’ve christened each other—all “sheltered young women who smilingly stumbled from the chintz-covered drawing-rooms of the suburbs straight into hell.” Their work is bloody in every sense of the word. Their nights are spent driving the wounded to field hospitals in the pitch dark, along slick muddy roads pock-marked with shell craters, aerial bombardment overhead. Their cargo is the bleeding, dying, jabbering remnants of battle: “shelves of mangled bodies … filthy smells of gangrenous wounds … shell-ragged, shell-shocked men … men shrieking like wild beasts inside the ambulance until they drown out the sound of the engine … .” Regardless of what time they finally crawl into their grubby, ice-cold “flea-bag” beds, 5 a.m. brings roll call, for which the women must be spic-and-span and fully dressed; 8 a.m. brings breakfast—like all meals, an indigestible slop that has their insides constantly in “revolt”—and by 10 a.m. they are cleaning their ambulances from the night before:

The stench that comes out as we open the doors each morning nearly knocks us down. Pools of stale vomit from the poor wretches we have carried the night before, corners the sitters have turned into temporary lavatories for all purposes, blood and mud and vermin and the stale stench of stinking trench feet and gangrenous wounds. Poor souls, they cannot help it. No one blames them. Half the time they are unconscious of what they are doing, wracked with pain and jolted about on the rough roads, for, try as we may—and the cases all agree that women drivers are ten times more thoughtful than the men drivers—we cannot altogether evade the snow-covered stones and potholes.

How we dread the morning clean-out of the insides of our cars, we gently-bred, educated women they insist on so rigidly for this work that apparently cannot be done by women incapable of speaking English with a public-school accent!

These gruesome experiences make for gripping reading, but, as the death toll begins to mount, there’s also a tortured sense of inevitability. Shock and sorrow gives way to detached desolation, and Price’s portrait of a woman “drained […] dry of feeling” is magnificent. So too is the late addition of a sub-plot involving the desperate procurement of a backstreet abortion (a notably daring inclusion for a novel from this era, especially given that the “fallen woman” in question is supposedly too well-bred to have had any pre-marital sex, let alone with three different partners.) It eviscerates absolutely any lingering sense of civility or romanticism. Although Nell survives the war, it costs her everything but her life. At the close of the book, her eyes “emotionless,” and her face wearing “an expression of resignation,” she’s the only one of forty people who clambers out of the bombed wreckage of a trench shelter physically unscathed. Her soul, however, has been completely destroyed.

The originality of the novel lies in its unflinching gaze, its insistence on telling the truth, however unpalatable. The truth about the privations the ambulance drivers have to put up with; that of the carnage of the battlefield—the searing image of the man, for example, who’s been reduced to a “gibbering, unbelievable, unbandaged thing, a wagging lump of raw flesh on a neck […] a lump of liver, raw bleeding liver, that’s what it resembles more than anything else”—but most of all, the truth of the unwitting evils perpetrated by those back in Blighty in the name in “patriotism.” Nell is furious with the politicians “we pay to keep us out of war and are too damned inefficient to do their jobs properly,” and the “flag-crazy” parents who send their sons and daughters to be slaughtered like cattle while they sit in their comfy drawing-rooms talking about how proud they are. “I am suddenly aware that I cannot bear Mother’s prattle-prattle of committees and recruiting-meetings and the war-baby of Jessie, the new maid,” she thinks as she travels home for a period of leave, “nor can I watch my gentle father gloating over the horrors I have seen, pumping me for good stories to retail at his club to-morrow.” She’s sickened by the realization that the last thing her parents and their friends want is for her to shatter their illusions of her honourable altruism. They wouldn’t have the stomach to face the reality, even if they wanted to, she thinks pityingly. “War is dirty. There’s no glory in it. Vomit and blood. Look at us. We came out here puffed out with patriotism. There isn’t one of us who wouldn’t go back to-morrow. The glory of the War … my God! …” One can well imagine what little patience Nell would have for the so-called patriotic Brits today who voted to leave the EU, especially those invoking Britain’s famous Blitz spirit as evidence that we’ll prevail despite all hard evidence to the contrary.

The intimacy and accessibility of Nell’s voice is intoxicating. With her unabashed outspokenness about the futility of war, Nell is a strikingly modern heroine. “Once I was a sweet girl, happy and interested in local things,” she explains, the genteel Edwardian young lady whose only concern is marriage and motherhood, “now I’m bitter and snappy and sarcastic and with a tongue like an adder, yes, and not above swearing, either, actually swearing.” Bar some of her more period specific slang, Nell is animated enough to give most contemporary “strong female characters” a run for their money.

*

Price herself lived a life of multiple acts to rival Nell’s extended exploits (the sequels to Not So Quiet see our heroine through a veritable roller-coaster of adventures). She claimed to have been born at sea, off the coast of Sydney, Australia, to English parents. Different sources give her birth date as 1888, 1896 and 1901—though one of the latter two seems the most likely. Having moved to London as a teenager, following the death of her father, Price pursued an early career on the stage, but by 1918 she was working as a journalist for the Sunday Chronicle. She married a soldier named Charles A. Fletcher in 1920, but he was supposedly killed in the Sudan four years later.

As well as her novels and journalism, she also experienced success as a playwright and screenwriter, including co-writing Once a Crook (1939)—which was then filmed in 1941—with her second husband, the Australian writer Kenneth A. Attiwill (whom she’d married in 1939, though she often dated their nuptials to 1929). In 1943, while Attiwell was a prisoner of war in Japan, and presumed dead, Price was appointed war correspondent for The People, and spent time in France and Germany. She was the first woman reporter to enter Belsen concentration camp after its liberation, and she interviewed Goering and covered the Nuremberg trials. Her next reinvention was perhaps even more surprising: after the war she became an extremely successful astrologer. She hosted a popular TV horoscope show in the UK, was the astrologer for She magazine for an incredible twenty-five years, and, after she and Attiwell returned home to Australia in 1975, she wrote the monthly horoscope column for Australian Vogue. When she died in 1985, Price was writing what would surely have been truly eye-opening memoirs, but sadly they remain unfinished and unpublished. Although her death did ignite a flurry of interest in her work—in 1988, Not So Quiet was reprinted in the UK as a Virago Modern Classic, and the following year it reappeared in America, released by The Feminist Press—this was short-lived and the book has once again fallen out of print in Britain.

Reading it now though, Price’s novel seems just as important as when it was first published nearly ninety years ago. This book is acutely relevant today; when we seem to have conveniently forgotten that peace—and very specifically, the prevention of another conflict to rival either the First or Second World Wars—was one of the most important foundational elements of the creation of the European Union.

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, The Financial Times, The New York Times Book Review and Literary Hub, among other publications.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2OxuIiU

Comments

Post a Comment