Kate Colby’s Dream of the Trenches is the book I never knew I needed. I wrote last week about my love for fiction about women interacting with art, and Colby’s unique blend of poetry, essay, and autofiction offers yet another angle into that conversation. She considers works by writers such as Ben Lerner and Virginia Woolf while incorporating her meandering thoughts into the ongoing narrative of “Driving to Margaret’s Mother’s Memorial Service.” In a stream of consciousness that roves I-195, Colby contrasts her literary critique with truisms and memories that careen the reader into questions about the nature of language. At the beginning of these musings, Colby notes that “writers tend to be preoccupied with what makes every thing unique, but I get hung up on the countless ways they clump.” Language and life congeal throughout Dreams of the Trenches, spanning topics from motherhood and middle age to metaphysical literature. Colby makes tongue twisters out of her inquiries, with exquisite turns of phrase such as “time let go and oblivious to dog hair.” She’s the kind of writer who notices both the windshield and the spec of dust on it, and Dreams of the Trenches is the kind of book that places them side by side and says, Look. —Nikki Shaner-Bradford

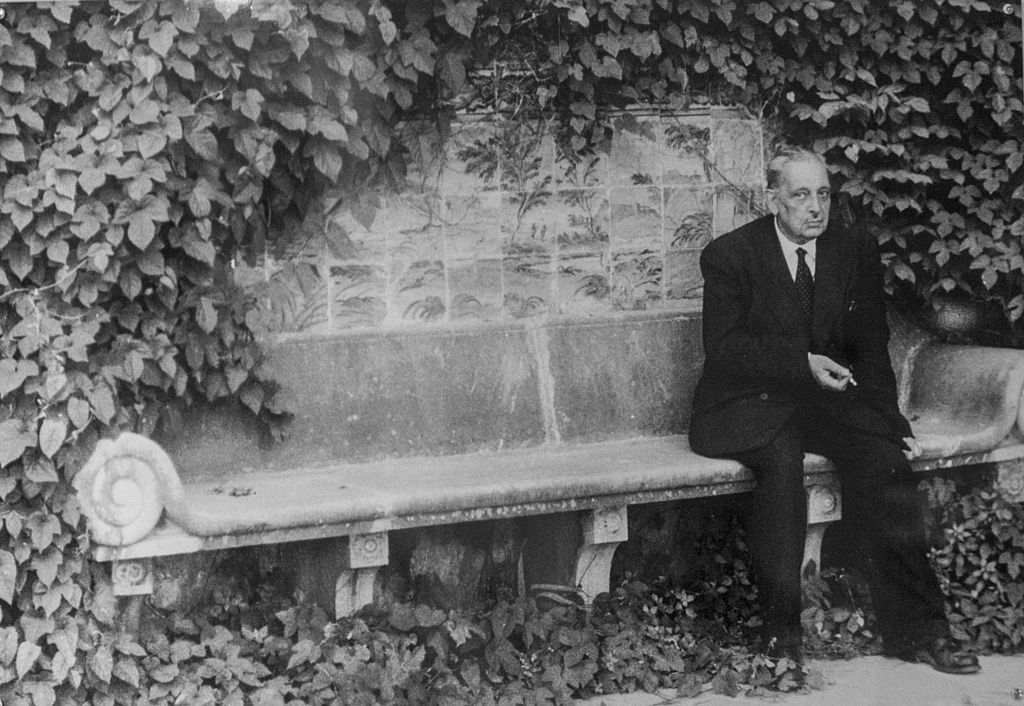

Like loving difficult people, loving a difficult book is hard to justify, not because you’re wrong but because what you love about it often eludes articulation. Carlo Levi’s memoir Christ Stopped at Eboli—based on his time as a political exile in Aliano (“Gagliano” in these pages, a nod to the local dialect, Alianese) from 1935 to 1936—is one such book. It is dense with despair and thick, like the hot air of malaria country, with hopelessness. The claustrophobic narrative begins with Levi’s arrival in Gagliano and ends with his leaving, and while we are meant to understand that Levi’s anti-fascist activity landed him in this position, he barely references it. This is not a political book. In the endless, empty days, there is only the whisper of a plot. What is it in this depressing book that offers enchantment? Maybe it’s that the characters are thrown into sharp relief against the squalid landscape. Levi renders his ensemble cast with empathy and precision: As a doctor and artist, Levi’s presence is welcomed by the gentry, who are bitter at their parochial situation and seek his friendship as a way of elevating their lowborn citizenship by proxy; as an exile, he earns kinship with the peasants, who recognize in him something of their own oppressed situation. The calculating Donna Caterina has both her husband and brother on strings (and designs on marrying her daughters to Levi); Giulia, the sturdy peasant woman Levi employs as a housekeeper, practices mysticism and is a loyal companion. Maybe I was won over by the vicarious escape from political turmoil I felt. In his introduction, Levi writes that his exiled self was “so free of his own era as to be almost exiled from time.” Maybe the appeal of a difficult book can be found in its relentless difficulty, its uncut intensity, which demands our fullest engagement as readers. —Lauren Kane

Every couple months, I turn, like a dog in the straw, and bed down with a title from the last century—or the century before that one. I knew that the reward of reading Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s The Leopard would unfold in every direction. “Reading and rereading it,” writes E. M. Forster, an early admirer, “has made me realize how many ways there are of being alive, how many doors there are, close to one, which someone else’s touch may open.” The novel, about a titled family in nineteenth-century Sicily, opens after the hour of the evening Rosary. Under the silk of the women’s dresses and the priest’s soutane, in a room bedecked with Roman gods, there is the stirring of the next tectonic shift on the Italian Peninsula. Written in the fifties, the book is about Lampedusa’s own ancestors, the Salina family, with whom a certain blessedness had died. Every blazing summer is the same for the House of the Leopard, but the coming revolution means a dozen small humiliations before eventually there are “horses bought with an eye more to price than to quality,” which I suppose signals the real end of the line. The joy is in the hunting in the hills and in the arguments for social niceties and in guessing Lampedusa’s more painful nostalgia from his perch in the midtwentieth century. The fun is also in speaking to friends and colleagues about the book now, another sixty years on, as the art of the letter fades underfoot and the arguments of social stratification echo as loud as ever. The Salinas are tempting not just because of their freedom from want—that quality is plenty on display in our own era. They are tempting because of their freedom from time and change and fad, which, in the 1850s, the 1950s, or 2019, is a bedtime story for all ages. —Julia Berick

In Dear Scarlet, Teresa Wong writes and illustrates the story of her experience with postpartum depression. Intrusive thoughts are blown up in large text, subtracted from blacked-out bubbles: “I FEEL LIKE A MONSTER.” Elsewhere we see quiet but similarly daunting images: simple bird’s-eye views of her baby surrounded by white space, tiny arms stretching out of her swaddle. The rendering—the variance in tone—feels true to life. It’s sometimes quiet, sometimes deafening, and always complex. Whatever the volume, there are always possibilities for suffocation but also for beauty and hope. Near the end, Wong tells her daughter: “I hope you never go through depression, postpartum or otherwise. But if you do, please know that I know what it’s like.” To name and acknowledge depression is already a gift. But within these pages, too, lie a visual guide and map of “what it’s like.” A wide view. Living with depression is like this, and this, and this. —Spencer Quong

When I lived in Palestine, I started listening to Mashrou’ Leila as part of an overly optimistic project of “improving my Arabic.” That undertaking went the way of all good intentions. Poor grasp of the language, though, shouldn’t keep anyone away from this band. Their latest album, The Beirut School, includes only three new songs, but the propulsive, hypnotic “Radio Romance” alone is worth the price of admission, and more importantly, seeing all these songs collected together reminded me of why I listen to them in the first place. Coverage of Mashrou’ Leila in the U.S. has tended to focus on the political, on what the band “represents,” and neglected to emphasize that honestly, the music is just a lot of fun. Maybe they’ve grown up—and a decade in, they’re certainly well aware of what they “represent”—but there is still humor here and joy; they seem to take as much pleasure as kids in making this music together. Even in the saddest songs, like “Shim El Yasmine” and “Inni Mnih,” something is being celebrated or appreciated—friendship or camaraderie or brotherhood, having someone to sing not to but with, which can be even more vital. For those who insist on seeing a band from “the Arab world” as political, though, I would point to Mashrou’ Leila’s cover of Britney Spears’s “Toxic,” which for some inexplicable reason did not make it onto this album but can be found in all its glory on YouTube. The video is among the most purely joyful things I have seen, and a good reminder that politically and personally, sometimes the best revenge is just living well. —Hasan Altaf

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2ENBb4I

Comments

Post a Comment