In the 1820s, when Honoré de Balzac decided to become a writer, the novel was a minor literary genre in France. Like Voltaire, educated French people preferred poetry and grand tragedy, wherein virtue, truth, enthusiasm, and hope marched solemnly across the page. As a result, contemporary French novelists were almost ashamed of their prose. Many published under pseudonyms—the men because their tone tended to be light, schoolboyish, and edgily anticlerical; the women because they knew to expect prim, frowning disapproval if they openly wrote for publication.

Then the sentimental novel began to win popularity. Writers such as Adelaïde de Souza, Sophie Cottin, Germaine de Staël, Madame de Genlis, and Madame von Krüdener gravitated toward Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s 1761 Julie, or the New Heloise, enriching its approach to prose with fresh narrative procedures that realist novelists would later adopt. With remarkable precision, these authors analyzed contemporary dilemmas regarding, for instance, the postrevolutionary longing for individual freedom and the enduring weight of social conformity. In foreign countries, they came to represent a sparkling inventiveness that was entirely French; the English, in particular, appreciated this inventiveness, comparing it to their own Samuel Richardson and Ann Radcliffe. Meanwhile, the Germans applied it in their attempts to explain the dichotomy between Moralität and Sittlichkeit (individual morality and the collective ethic, respectively).

The contemporary French sentimental novel exported well to the rest of Europe, though most modern literary histories would have us forget it ever existed. The fact was that between Paris, London, and Weimar, a Romantic genre was circulating: the French variant, largely produced by women, offered non-French people a keener understanding of the literary specificity of France than the idiosyncratic prose of the Romantic François-René de Chateaubriand or Benjamin Constant. Indeed, these sentimental novels alerted sensitive observers all over Europe to the painful destinies of fictional characters who lived as outcasts from their own existences, and also to the French approach to a human predicament that was as noble as it was vulnerable. Literature, in the first three decades of the nineteenth century, was much concerned with human passions at odds with social norms, and it tailored itself directly to readers—especially women—who now sought to define themselves through their characters rather than their conditions. Natural sensibility became the equivalent of a literary passport.

Then came Sir Walter Scott. The Edinburgh-based poet of The Lady of the Lake and author of The Bride of Lammermoor swiftly became world famous as the author of the Waverley novels. In 1814, when he began his mighty series, Scott was already noted for his poems and stories. Waverley inaugurated a sensational new writing manner and method, which was translated and reprised by others throughout the nineteenth century, from Sweden to Portugal and from Brazil to Japan. The global Waverley mania is hard to imagine today, but Harry Potter and Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy might be reasonable comparisons.

There was a threefold novelty about Scott’s fresh brand of historical fiction. To start with, the fabric of his stories was resolutely national. Scott’s theme was the people of Scotland; his literary mission was to convey, through fiction, the cultural and social autonomy of a country that could aspire to political independence. In place of the abstract humanity of the sentimental novel, Scott described the community of a nation in the making.

Scott’s Waverley novels, whose titles placed end to end—Ivanhoe, The Fair Maid of Perth, Quentin Durward, Guy Mannering, Waverley, et cetera—followed the chronological history of the Scottish nation from the eleventh to the nineteenth century, crystallized a broader national turn within European literature. This exploration of the national past injected the energy of a real future into a community that was groping for its identity. To succeed, the novel would have to appear believable, credible. Scott thus wove his plots into the customs and legal frameworks of ancient periods. Documentary evidence, discreet though it was, gave his fiction a truthfulness and authenticity that had never been seen before. Scott expressed historical truths, drawn from existing archives, through the prism of art.

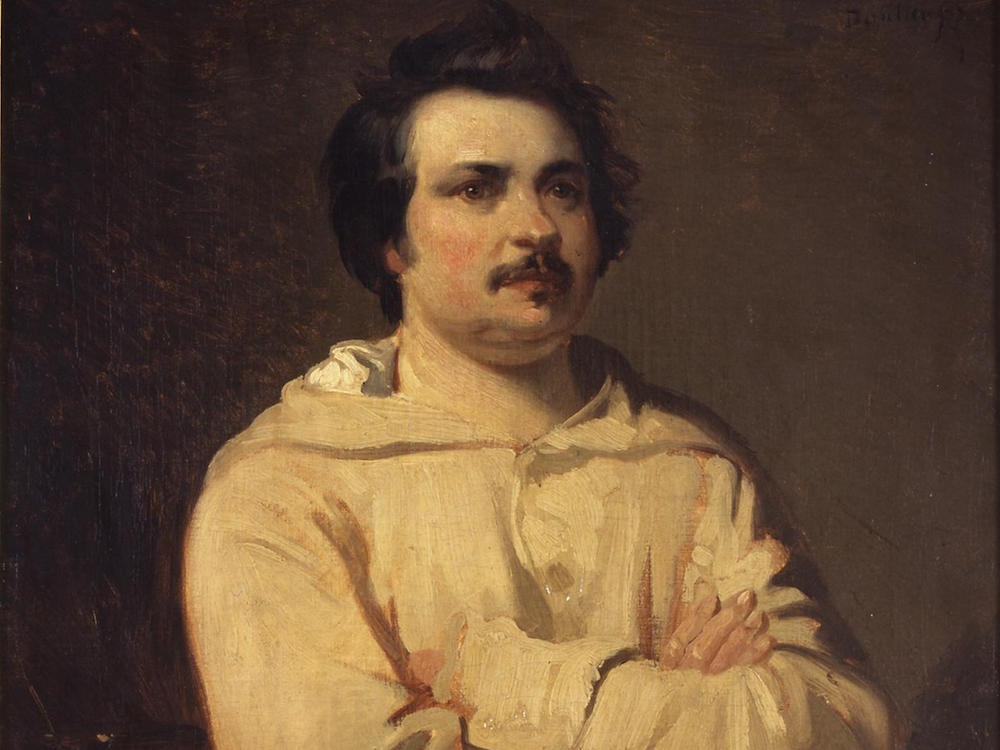

This daring new approach to literature proved fascinating to French historians and novelists. Augustin Thierry, Prosper de Barante, Jules Michelet, Alfred de Vigny, Prosper Mérimée, and Victor Hugo were galvanized by Scott’s “patriotic erudition.” So, too, was Balzac, beginning with The Chouans, his 1829 novel on the French Revolution. In the end, he proved more faithful to Scott’s model—a series of linked novels—than any of his contemporaries. Like the great Jules Michelet, author of a nineteen-volume history of France, Balzac believed that historians should concentrate “on the people, not only on its leaders or institutions.” Unlike Michelet, he deemed it imperative to describe and understand the manners and customs of his own time. Half a century after the dramatist Louis-Sébastien Mercier first attempted to classify social types in his Tableau de Paris, the French nation was still in search of itself following the maelstrom of the Revolution and the Napoleonic Empire. Balzac believed it was his duty as a French writer to revisit Paris and the provinces and show what his country had become. Literature had an important role to play as a symbolic space in which his compatriots could come together, identify and repair the injustices caused by the market and social mobility, and restore a semblance of community to France.

Thus the world of his Human Comedy is emphatically not that of the sentimental novel. Balzac’s stories are not set in Russia, the East, or America, but in Paris and the French provincial towns of Tours, Angoulême, and Douai. Here, exoticism begins at home and cultures collide when French people encounter their neighbors. When a French soldier gets lost in Upper Egypt (“A Passion in the Desert”), he falls in love with a leopard; perhaps, being French, he finds it easier to cross the animal frontier between species than the cultural frontier separating nations. Every social bond in Balzac’s literary universe is formed between groups whose members know themselves to be compatriots. His networks of bankers, shopkeepers, judges, doctors, soldiers, elected officials, artists, and intellectuals overlap within a dense social and urban space, a common territory laden with history and rich with a shared future. Balzac’s novels create their own community within the strict confines of an imagined country, inviting readers to recognize one another in the social types that thronged postrevolutionary France: the upstart, the parvenu, the bankrupt, the shell-shocked soldier, the genius, the woman obsessed with a fickle lover, the domestic housewife, the unscrupulous seductress, the subservient daughter, the betrayed cousin, and so on ad infinitum.

Balzac’s characters, when they are not French, are most often German, English, Italian, Spanish, or Brazilian. Their nationality is expressed in their manners or their accents. By having the Baron de Nucingen speak with a recognizable German accent, for instance, Balzac exaggerated a difference for which the defining criteria were national. The humor rested on the distance now separating the French spirit from a common history, culture, and wit. Readers were expected to laugh at this German because he was not French—even though he may have had other sterling qualities.

Scott’s worldwide success released a flood of nation-centric novels elsewhere. Balzac’s novels embraced this assignment for literature: assembling—or reassembling—a nation. In their wake, writers across the world declared themselves “realists”—by which we should understand that they tapped Balzac’s realism to write histories of the current era (rather than Scott’s distant eras) and explore contemporary tensions within newfangled national communities. The worldwide transformation that French literature made its own and announced in 1842, when the first volume of the Human Comedy came out, was dual: the separation of cultures into nations and the globalization of literary universes, now confined to nation-states.

And yet … another form of literary cosmopolitanism was reinventing itself within the walls of the French university. In 1830, Claude Fauriel was appointed inaugural professor of “foreign literature” at the Sorbonne. A polyglot translator who had come late to higher education, Fauriel built upon the comparative grammar of the Enlightenment while turning his attention to pre-Romantic German philology. He felt that if certain peoples create literature, then it is up to anthropology to find the reasons why; not so much through philosophical speculation about the origins of languages and poetry as through the application of rigorous historical research to literary exchanges. The notion of “world literature” (Weltliteratur) suggested by Goethe between 1827 and 1832 rested on a similar conviction: the idea of literary nationality, which is but an exception in the history of mankind, should never obscure the fact that cultural exchanges have always predated political borders.

Fauriel devoted a chapter of his History of Provençal Poetry to the influence of the Arabs on French literature. It is rare that this idea is given much thought anymore. Nevertheless, one might be forgiven for wishing that it could be more widely discussed in our own time.

—Translated from the French by Anthony Roberts

Jérôme David is a professor at the University of Geneva, specializing in French literature and the teaching of literature.

Anthony Roberts is a freelance writer, journalist, poet, and prizewinning translator. He currently lives in France.

From France in the World: A New Global History. Edited by Patrick Boucheron, English-language edition edited by Stéphane Gerson. Used with the permission of Other Press. Copyright © 2019 by Jérôme David.

from The Paris Review http://bit.ly/2VCCtqn

Comments

Post a Comment